news, latest-news, ben morton, public sector wage rises, public sector pay rises, public service pay, public service wages, public sector wage policy, saul eslake, andrew podger

Public servants operating under a new Commonwealth public sector wage policy will likely get a smaller pay rise than they would have under the old system, one economist has warned. The Coalition government on Friday announced it would scrap the former 2 per cent wage rise cap for public servants and tie wages to the private sector via the Wage Price Index. It means that public sector wages can no longer exceed private sector increases. But should the Wage Price Index grow beyond 2 per cent, public servants could negotiate a pay rise of more than 2 per cent. Economist Saul Eslake said due to the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic, any public servants negotiating a wage increase in the near future could expect a smaller wage increase than under the old policy. “I think it probably means public servants will get smaller pay rises than they would have done otherwise, especially this financial year,” Mr Eslake said. “Where they might have got somewhere between CPI [Consumer Price Index] and 2 per cent, they’ll get less than that because the Wage Price Index will go up by less than that.” Importantly, the new policy will be implemented as current agreements expire and are renegotiated. Existing arrangements will be allowed to run their course. However, it highlights an aspect of the policy criticised by Labor and the unions, that public servants will be worse off during periods of economic downturn. The Assistant Minister to the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Ben Morton, said the policy would bring public servant wages more in line with other Australians. “This new policy means Commonwealth public sector employees will directly benefit from ensuring the government’s plan to strengthen the economy, create jobs and deliver private sector wages growth succeeds,” Mr Morton said. READ MORE: Mr Morton said the government considered information from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Treasury forecasts and APS Remuneration Report data to determine the new policy. Mr Eslake said public servants being asked to accept smaller wage increases during a recession was not unreasonable and could be viewed as a trade off for job security. He also saw little weight to the argument that smaller APS pay rises would rob the economy of more money at a time the government was actively trying to boost consumer spending. Considering the Commonwealth public sector had a workforce of around 246,000, it was relatively small and made up of people who would have roughly 40 per cent of a pay rise taxed and would be more likely to save the rest. Former Public Service Commissioner Andrew Podger said he had no strong objections to tying APS wage increases more closely to the market. However, he said it was a pointless exercise if you did not first establish an acceptable baseline for public sector remuneration before leaving it to be dictated by market forces. Variations in wages between poor and rich agencies had been allowed to develop, Professor Podger said, and this needed to be addressed before altering the method of determining wage increases. Both Mr Eslake and Professor Podger argued that remuneration needed to attract and retain key skills with the public sector. Mr Eslake said that if, under the new policy, it became clear the public service was not attracting the appropriate talent, the policy would need to be varied.

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/fdcx/doc7cmfk1bp2qb6nnm3kux.jpg/r1363_1150_5196_3316_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

Public servants operating under a new Commonwealth public sector wage policy will likely get a smaller pay rise than they would have under the old system, one economist has warned.

It means that public sector wages can no longer exceed private sector increases. But should the Wage Price Index grow beyond 2 per cent, public servants could negotiate a pay rise of more than 2 per cent.

Economist Saul Eslake said due to the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic, any public servants negotiating a wage increase in the near future could expect a smaller wage increase than under the old policy.

“I think it probably means public servants will get smaller pay rises than they would have done otherwise, especially this financial year,” Mr Eslake said.

“Where they might have got somewhere between CPI [Consumer Price Index] and 2 per cent, they’ll get less than that because the Wage Price Index will go up by less than that.”

Importantly, the new policy will be implemented as current agreements expire and are renegotiated. Existing arrangements will be allowed to run their course.

However, it highlights an aspect of the policy criticised by Labor and the unions, that public servants will be worse off during periods of economic downturn.

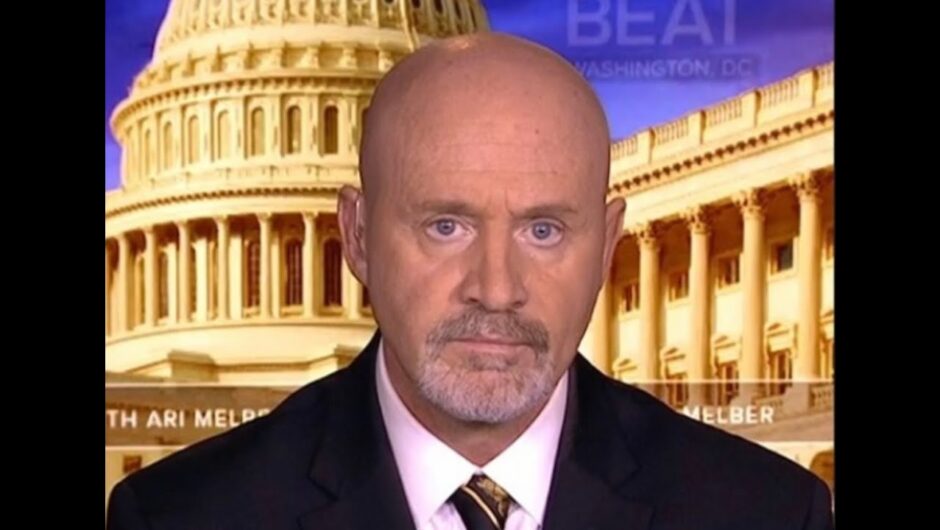

The Assistant Minister to the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Ben Morton, said the policy would bring public servant wages more in line with other Australians.

“This new policy means Commonwealth public sector employees will directly benefit from ensuring the government’s plan to strengthen the economy, create jobs and deliver private sector wages growth succeeds,” Mr Morton said.

Mr Morton said the government considered information from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Treasury forecasts and APS Remuneration Report data to determine the new policy.

Mr Eslake said public servants being asked to accept smaller wage increases during a recession was not unreasonable and could be viewed as a trade off for job security.

He also saw little weight to the argument that smaller APS pay rises would rob the economy of more money at a time the government was actively trying to boost consumer spending.

Considering the Commonwealth public sector had a workforce of around 246,000, it was relatively small and made up of people who would have roughly 40 per cent of a pay rise taxed and would be more likely to save the rest.

Former Public Service Commissioner Andrew Podger said he had no strong objections to tying APS wage increases more closely to the market.

However, he said it was a pointless exercise if you did not first establish an acceptable baseline for public sector remuneration before leaving it to be dictated by market forces.

Variations in wages between poor and rich agencies had been allowed to develop, Professor Podger said, and this needed to be addressed before altering the method of determining wage increases.

Both Mr Eslake and Professor Podger argued that remuneration needed to attract and retain key skills with the public sector. Mr Eslake said that if, under the new policy, it became clear the public service was not attracting the appropriate talent, the policy would need to be varied.