“He hasn’t got s—,” one SAS soldier boasted at a barbecue in Perth in 2017, according to others who overheard him. It would be alleged later by eyewitnesses that this soldier ordered the execution of prisoners in 2009. But those allegations would not come out for many months, well after a small clique of SAS soldiers banded together to plot how to discredit any allegations that might reach Brereton’s ears.

Smashing the code of silence

There were other reasons to be doubtful of Brereton’s prospects. Inquiries into war crimes in the US and UK had both collapsed under political pressure, including that brought by President Donald Trump. And in Canberra, defence had a well-founded reputation for burying bad news.

Even if SAS whistleblowers emerged – and that was a big if – it was uncertain if the quietly spoken, amiable Brereton, along with Defence Force chief General Angus Campbell, would ensure their stories were probed exhaustively. If those stories were then found to be corroborated, would they be relayed to police for possible prosecution? And would any of it be released to the Australian public?

Brereton’s trip to Afghanistan in July last year laid some of these unknowns to rest. By the time the judge arrived in Kabul, he had smashed the SAS code of silence. Multiple defence sources have confirmed that whistleblowers had already confessed on oath to executions or having witnessed their SAS soldier colleagues murder Afghan prisoners.

Loading

On the ground in Afghanistan, according to local sources, the judge met villagers from the country’s south who further corroborated these stories.

The question of whether the public would ever be told of the shocking scale of the war crimes scandal was put to bed on Thursday morning. In a press conference to reveal Brereton’s key findings, Campbell excoriated the elite soldiers who allegedly committed war crimes – the suspected murders of 39 Afghan prisoners and civilians – betraying their SAS and Commando colleagues and the nation in whose name they served.

Campbell said Brereton had uncovered a “disgraceful and a profound betrayal of the Australian Defence Force’s professional standards and expectations”.

When Paul Brereton was appointed a judge of the Supreme Court of NSW in August 2005, he was walking in the steps of his father, Justice Russell Brereton, a judge who served for two decades on the same court.

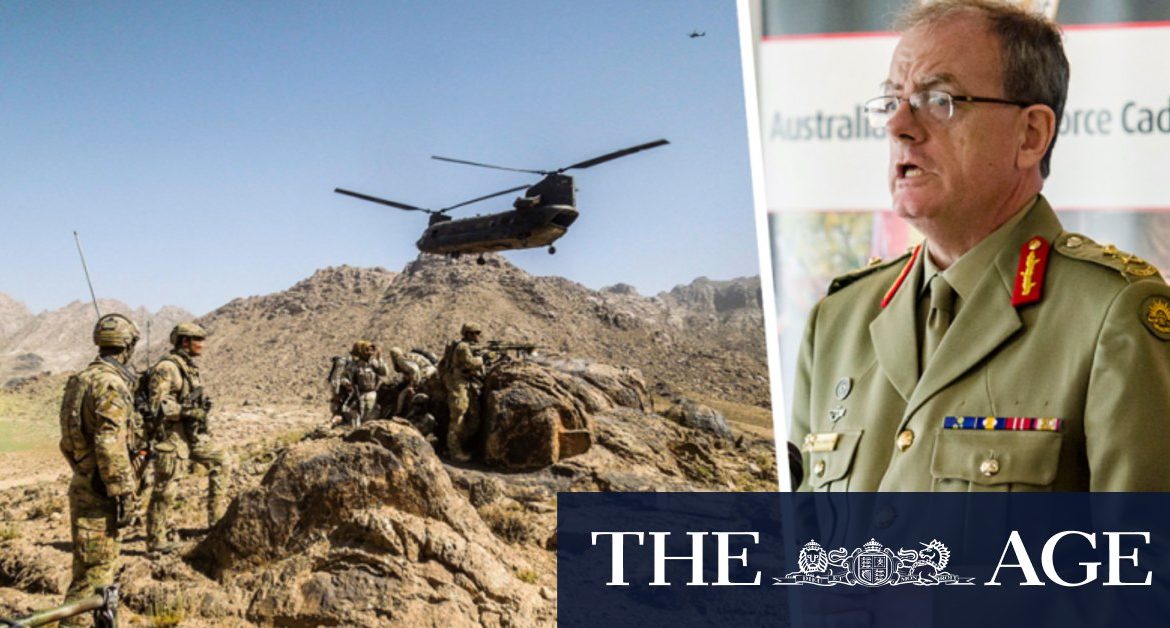

Justice Paul Brereton, who has recommended Defence Force chief Angus Campbell refer 36 matters to the Federal Police for criminal investigation involving 23 incidents and 19 individuals.Credit:

The NSW bar noted the younger Brereton’s courage in fighting for justice as a barrister who “stepped forth where others may have feared to tread,” as well as his passion acting pro bono for military veterans.

Also like his father, Brereton became a senior officer in the reserves. But where his father had prosecuted Japanese soldiers for war crimes in 1945 – after Australia had helped win the war and the public were baying for the defeated Japanese to be held accountable – Brereton junior was given a far less straightforward task.

In April 2016, after a preliminary investigation by army consultant Dr Samantha Crompvoets had heard multiple disclosures by SAS and Commandos of shocking war crimes, Justice Brereton was tasked with finding more evidence to back up or discount the claims. Public pressure was inevitable, as the accused and their supporters sought to denigrate what became known as the Brereton Inquiry.

The war in Afghanistan was one that many Australians had lost track of. It had dragged on for 15 years after the September 11 attacks first led to a Western coalition invading the battle-weary nation. As the war’s progress stagnated, the bravery of individual elite special forces soldiers on capture and kill missions informed the public narrative pushed by defence and successive governments. Much of it was true.

But while Brereton’s inquiry would concentrate on the actions of a relatively small number of soldiers who allegedly went rogue – 25 soldiers are allegedly responsible for 39 murders – it would inevitably risk tainting Australia’s entire Afghan contribution.

‘Enormous challenges’

Justice Brereton has never spoken publicly about his work, but an annual report released by the Office of the Inspector-General in February gave the first glimpse of the judge’s methodology. He appointed a small team of trusted military lawyers, led by experienced barrister Matt Vesper. More lawyers and investigators could have expedited the probe, but a larger, less cohesive taskforce would be at risk of skating over key lines of inquiry. Instead, Brereton’s small team focused on building personal bonds of trust with SAS and Commando whistleblowers.

In his report released on Thursday, Brereton described “enormous challenges in eliciting truthful disclosures in the closed, closely-bonded, and highly compartmentalised Special Forces community, in which loyalty to one’s mates, immediate superiors and the unit are regarded as paramount, in which secrecy is at a premium, and in which those who ‘leak’ are anathema.”

“In such an environment, it is hardly surprising that it has taken time, opportunity, and

encouragement for the truth to emerge, and that it has not necessarily done so at the first

opportunity or interview, or fully. It is often not the first, or even the second, interview at which the story, either full or in-part, emerges; it takes time for trust to be established, and for the discloser’s conscience to prevail over any impediments.”

Most of Brereton’s witnesses had served in Afghanistan and many were also mentally scarred by their service.

Brereton also appointed an officer dedicated to witness welfare, especially for whistleblowers facing mental health pressures.

One of the few public whistleblowers, SAS medic Dusty Miller, described in August how Brereton not only painstakingly recorded his testimony about the alleged execution of an injured and unarmed Afghan farmer, but later personally called Miller to check on his mental state.

A PR offensive

From the start the Brereton inquiry was clear about its aims. Its focus would not be on “fog of war” or “heat of the moment” incidents. but only egregious and cowardly executions of Afghans prisoners.

No potential evidence was seen as out of reach. Brereton’s trip to Afghanistan in 2019, accompanied by federal police detectives, was aimed at corroborating the statements of what the federal police later described in a letter as SAS “eyewitnesses”.

While Brereton investigated, he refused dozens of media interview requests. But where Brereton stayed silent, his critics did not. Those sceptical of his exhaustive inquiry approach, or the fact that alleged war crimes were being probed at all, suggested inaccurately that minor “heat of the battle” incidents were under scrutiny.

Meanwhile, reporting in The Age and the Herald was naming one of Australia’s best-known Afghanistan veterans, Victoria Cross recipient Ben Roberts-Smith, as having participated in the execution of prisoners.

Former prime minister Tony Abbott urged Australians not to rush to judge soldiers who were “operating in the heat of combat under the fog of war”. Former defence minister Brendan Nelson, a close friend of Roberts-Smith, made similar comments.

Ben Roberts-Smith, middle, after receiving his Victoria Cross in 2011.Credit:ADF

Roberts-Smith himself hired a team of lawyers and an expensive public relations firm, run by Sue Cato and employing ex-journalist Ross Coulthart, to counter the serious war crimes allegations he vehemently denies. Seven West Media chairman Kerry Stokes, a backer of Roberts-Smith who employed him as a senior manager in 2015, funded a defamation action against The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald, while Roberts-Smith’s defamation lawyer, Mark O’Brien, made a formal but false complaint that the Brereton inquiry was biased and leaking information.

Loading

Brereton demolished O’Brien’s unfounded claims in a forensic online report published by the Office of the Inspector-General, but not before they were published on the front page of a national newspaper. Roberts-Smith more recently joined the fray himself, releasing a statement that sought to portray Brereton’s inquiry as little more that a rumour collection exercise, rather than a forensic investigation based on thousands of files, videos and photos and hundreds of interviews conducted on oath with soldiers and officers who fought in Afghanistan.

In September 2019, a now former reporter from The Australian, Paul Maley, launched a ferocious attack on Defence for defending the time Brereton was taking to collect his evidence.

“Ask the Defence Force why it is taking so long and you’ll get an answer about the complexity of the inquiries, the transnational nature of the inquiry, the fact the material is secret,” wrote Maley. “Don’t believe a word of it.”

These media critics were swinging in the dark, unaware of what Brereton was actually doing and apparently blind to the possibility that rogue soldiers trained in secrecy and counter-surveillance were working hard to defeat his inquiry.

‘No turning back’

Efforts to derail the probe were failing, and others gradually spoke up in Brereton’s defence, led by former SAS captain turned Liberal politician Andrew Hastie. Hastie’s stance risked upsetting some of his former SAS comrades but created vital political support for Brereton. The defence top brass also backed the judge, sources said, led by General Angus Campbell. By the end of 2019, multiple Special Forces operators had confessed to Brereton that they had executed prisoners, according to these soldiers’ supporters.

“There was no turning back,” said one senior defence figure.

Throughout 2020, fresh confessions were still being made. But it wasn’t until Thursday morning that the full scale of the Brereton inquiry’s findings were made clear, with allegations of 39 murders and 19 current or former soldiers to face criminal investigation and the possible stripping of their medals. He reported patrol commanders “blooding” young soldiers by forcing them to shoot a prisoner to achieve their first kill, and carrying “throwdowns” – weapons to be placed with the bodies of dead villagers so that in photographs they appeared as combatants.

Loading

The decision to refer soldiers facing the most serious allegations to police reflects Brereton’s cautious judicial approach. Other judges running commissions of inquiry have named offenders in their final reports, after deciding that the risk of prejudicing a jury in a criminal trial that may never eventuate is outweighed by the need to inform Australians about matters of grave public interest.

Defence insiders say that inherent in Brereton’s decision not to name any soldier is his strong desire not to prejudice any future trials. This is suggestive of a belief that individual accountability for alleged war crimes that have shamed the nation should ultimately play out in a criminal court before a jury, rather than via Brereton’s own assessment of a person’s conduct.

It also suggests that criminal trials of special forces soldiers are likely to occur over the coming years – grim news indeed for those who have long bayed for the scandal to be quickly buried.

If you are a current or former ADF member, or a relative, and need counselling or support, contact the Defence All-Hours Support Line on 1800 628 036 or Open Arms on 1800 011 046.

Nick McKenzie is an investigative reporter for The Age. He’s won nine Walkley awards and covers politics, business, foreign affairs and defence, human rights issues, the criminal justice system and social affairs.

Gold Walkley award-winning journalist and author. He was the first Australian journalist to be embedded with special forces in Afghanistan,

Anthony is foreign affairs and national security correspondent for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age.

Most Viewed in National

Loading