He had many nicknames — ‘Golden Boy’, ‘Moptop’, ‘Cosmic Kite’, ‘God’ — but, ironically, the name which best captured this colourful character and the operatic saga of his life was his real one: Diego Armando Maradona.

Argentina’s favourite son and one of world football’s greatest ever players died today in his home in Buenos Aires from a heart attack, bringing to an end a life overflowing with glory and gross excess.

Maradona was a street urchin from a Buenos Aires slum whose natural genius with a football was complemented by a bloody-minded will to succeed.

That he played football like a God made him a figure of worship all over the world, but particularly in his homeland and in Naples, Italy, where he played at his peak.

While he may have appeared god-like on the pitch, in reality he was just a man — and the adulation gradually crushed him.

Intense pressures on and off the field, and a penchant for the kind of debauchery that can only come when nobody in your world ever tells you ‘no’, led to years of drug abuse, controversies and bizarre behaviour.

His flaws, writ large by a voracious media, never diminished the love many Argentinians felt for him, especially the poor and underprivileged, who always saw him as their talisman, conquering the world.

“He is a divine figure.”

And Maradona did conquer the footballing world. He won club titles in Argentina and Italy and the 1986 World Cup with his national side. Many came to regard him as the best of all time, with the legendary Brazilian Pelé the other serious contender.

Perhaps to placate fans of both, or to prevent a war between Argentina and Brazil, Pelé and Maradona jointly won FIFA’s Player of the Century in December, 2000.

Loading

Golden Boy never lost his sense of mischief

Short and stocky, Maradona’s low centre of gravity and incredible ability with the ball made him a wriggling, slippery menace for opposing defenders.

Playing as a midfielder or forward, he also possessed astonishing vision — an ability to read a game and open it up with a single pass or dribble.

“He had complete mastery of the ball,” said former Barcelona teammate José Carrasco.

“When Maradona ran with the ball or dribbled through the defence, he seemed to have the ball tied to his boots. I remember our early training sessions with him: the rest of the team were so amazed that they just stood and watched him.

“We all thought ourselves privileged to be witnesses of his genius.”

His childlike attitude to the game could manifest itself in many ways, both negative and positive. He was petulant at times, but mostly joyous to watch. His sense of mischief saw him try things nobody else could even imagine.

‘I have two dreams’

Maradona was born on October 30, 1960 in the Villa Fiorito shantytown on the outskirts of Buenos Aires — the fifth of eight children.

He received a football as a gift for his third birthday and from that point on, the game would consume him. The ball and Diego never parted company. He started joining in the children’s pick-up games on the dirt pitches of the neighbourhood, and it soon became apparent he was special.

At the age of eight he joined Las Cebollitas (The Little Onions), a feeder team for professional outfit Argentinos Juniors. When he first showed his skills the coaches told him to go home and bring back his ID, as they didn’t believe someone so young could do what he was doing.

Word of his talent started to spread, and soon he was performing tricks to entertain the crowd at half-time during the senior team’s matches.

Grainy black-and-white footage of a young Diego shows him playing keepy-uppy with ridiculous ease, before he says to the camera: “I have two dreams. My first dream is to play in the World Cup. The second is to win it.”

He signed with Argentinos at age 14 and made his first-division debut in 1976, 10 days before his 16th birthday.

Four months later he became the youngest Argentine to play for the national team, making his debut in a friendly against Hungary — and though he was left out of the 1978 World Cup-winning side due to his youth, he won the Junior World Championship the next year as an under-20.

From the slum to the pinnacle of football

Maradona played 490 official club games during his 21-year professional career, scoring 259 goals. For Argentina he played 91 times and scored 34 goals.

Though he became best known for his love of Boca Juniors, he spent the majority of his early career at Argentinos Juniors — five seasons saw him amass more than 100 goals and a reputation for obscene outbursts of skill. The skills displayed proved he was not just a golden child but the real deal — and as a result he became the great hope of Argentinian football.

With every team in Argentina chasing his services, the only two realistic options were the country’s greatest clubs, River Plate or Boca Juniors. Though River offered him more money, only one choice was possible for Diego; the team he’d adored since childhood, the team associated with the poorer classes and a gutsy fighting spirit: Boca.

His first stint there would be a short one, as his talents drew attention from across the world. In 1981 he led Boca to the championship, scoring 28 goals in 40 games, before promptly taking up an offer from European superpower Barcelona with a then-world-record $9 million transfer fee.

Maradona’s time at the Catalan club was not a happy one. His relationship with club officials was fraught, and he was subjected by brutal treatment from opposing players, who hacked at his legs with little consequence, until Athletic Bilbao’s Andoni Goikoetxea broke one of his ankles.

It was during this period that the young Argentine became increasingly enamoured with the Barcelona nightlife, and first began taking cocaine.

There were some highlights on the pitch, most notably when he became the first Barcelona player applauded by the crowd at Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu stadium after an astonishing El Clásico performance.

But his two seasons in Spain ended in ugliness.

After the 1984 Spanish Cup final in which he was roughed up on the pitch and subjected to racist abuse from Athletic Bilbao players and fans, Maradona was at the centre of an all-in brawl between both squads, hurling flying kicks at the opposition while 100,000 fans, including Spain’s King Carlos, watched on.

Barcelona officials had seen enough, and ended their relationship with him.

‘I saw Maradona, oh mamma, and I’m in love’

In what looked like a step backwards, in 1984 Maradona signed with unfashionable southern Italian side Napoli, again for a world-record fee — sending fans of the club into delirium.

‘Italy’s poorest club signs the world’s most expensive player,’ read one headline at the time.

His time in Naples would be the most triumphant of his football career.

Maradona inspired Napoli to their first ever title in 1987, a UEFA Cup in 1989 and another Italian title in 1990.

Loading

For a club that had never before been able to compete with the rich northern giants, this was an extraordinary period of success. And Neapolitans had no doubt who to thank for it.

Maradona ascended to the same God-like status in the south of Italy as he enjoyed in his homeland. His fierce determination, defiant swagger and streetwise playing style made him an immensely appealing character to the residents of the tough port city.

“Maradona is a God to the people of Naples,” said Italy legend and Neapolitan Fabio Cannavaro.

“Maradona changed history … to live those years with Maradona was incredible.”

His genius on the field every weekend became the city’s primary form of escapism.

“Oh mamma, mamma, mamma,” they sung in the terraces and in the streets.

“Oh mamma, mamma, mamma, do you know why my heart is beating?

“I saw Maradona, I saw Maradona, eh, mamma, and I’m in love.”

But after seven years of glory, Diego’s time in Naples ended in scandal. His less-than-savoury extracurricular activities and criminal connections had long been common knowledge, but as Italy’s battle against the Mafia ramped up, authorities stopped looking the other way.

In 1991 Maradona was handed a 15-month ban for a positive doping test and was charged for possession of cocaine. He was also investigated for tax fraud and links to organised crime.

Even the club itself ran out of patience, suing him for damaging its image and fining him heavily for missing training and matches.

Maradona served his ban then refused to return to Naples.

He played a stint with Spanish club Sevilla, then returned to his homeland, briefly appearing for Newell’s Old Boys — where he was kicked out after being caught with half a kilo of cocaine — before ending his career with two seasons at his beloved Boca.

After leaving briefly to coach, Maradona made one final comeback for Boca before failing another drug test and retiring once and for all in 1997 on his 37th birthday.

He has taken up several short-term coaching roles since, but never enjoyed sustained success. Most notably he coached Argentina at the 2010 World Cup, where his sideline antics and hilarious press conferences outshone the team — led by his heir Lionel Messi — itself.

The ‘Hand of God’ and ‘Goal of the Century’ come minutes apart

It was on the international scene that Diego enjoyed his most iconic moments, including scoring perhaps both the greatest and most infamous goals of all time — in the same match.

Those who rate him as the best footballer of all time point to the 1986 World Cup victory for Argentina as proof. Never before or since has a single player had such a substantive impact on a tournament.

Maradona dragged a mediocre Argentina outfit to glory through a combination of sublime skill and sheer force of will.

He had debuted at the World Cup in 1982 in Spain, but endured a torrid time — unprotected by referees, he was fouled mercilessly and well contained by Italy and Brazil, before being sent off for violent play as Argentina bowed out to their South American rivals.

By the time the Mexico World Cup rolled around in 1986, Diego was 25 years old, the captain of his side and the best player in the world.

In the quarter-final against England, the best and the worst of Maradona was showcased in a matter of minutes.

The match was taking place just four years on from the Falklands War, which many Argentinians, including Maradona himself, still felt aggrieved by — and victory over England packed an extra emotional punch, whether it was achieved by fair means or foul.

With the game locked at 0-0, Maradona drove at the England defence before leaping for a deflected ball which lobbed towards goal. Despite being 20cm shorter than England goalkeeper Peter Shilton he managed to beat him to the ball and turn it into the net.

The referee awarded the goal as Argentinian players wheeled away in celebration. Maradona had, of course, used his hand to knock the ball in.

After the match when replays made it obvious he had cheated, Diego said the goal was scored, “A little with the head of Maradona, and a little with the hand of God.”

In the 2019 Asif Kapadia documentary about his life, Maradona showed no remorse for his nefarious goal.

Loading…

“We, as Argentinians, didn’t know what the military was up to [during the Falklands War]. They told us that we were winning the war. But in reality, England was winning 20–0. It was tough.

“The hype made it seem like we were going to play out another war. I knew it was my hand. It wasn’t my plan but the action happened so fast that the linesman didn’t see me putting my hand in.

“The referee looked at me and he said: ‘Goal’. It was a nice feeling, like some sort of symbolic revenge against the English.”

Just four minutes later scored what would become known as ‘The Goal of the Century’.

Taking possession near the halfway line, he skipped and slalomed through the majority of the English team before dinking the ball past Shilton. There was no doubting the legitimacy of that second goal, which also legitimised Maradona’s greatness in 11 breathtaking seconds.

England striker Gary Lineker could only watch in awe.

“When Diego scored that second goal against us, I felt like applauding. I’d never felt like that before, but it’s true … and not just because it was such an important game,” he said.

Maradona further enhanced his reputation with a brilliant solo performance in the semi-final against Belgium before setting up the winning goal in the final against West Germany. Argentina was world champion and Maradona cemented his status as an eternal hero to its people.

A diminished Diego carried an ankle injury into the 1990 World Cup in Italy but nevertheless still managed to guide a dour Argentina side to the final, again against West Germany. This time, in a turgid affair, the Europeans prevailed.

Four years later in his last World Cup in the USA, Maradona was sent home in disgrace after testing positive for ephedrine. His manic celebration of a goal against Greece became infamous in the wake of the doping revelations.

A life of turmoil and scandal

From the time he was at Barcelona in his early 20s, Maradona’s life was beset by drug and alcohol abuse, personal turmoils and scandal. He endured numerous health scares after retirement, with his weight fluctuating wildly.

“Everything about Maradona is exaggerated — the good and the bad. As a player he was number one. He can be charming, but in his private life he broke all the rules,” La Nacion sport editor Daniel Acrucci told AP.

After leaving Spain in some disgrace following the brawl with Bilbao, Diego found himself in his element in Naples, where the locals worshipped him for bringing his immense talent and profile to the city, to the extent where he could get away with almost anything — for a while at least.

Kapadia’s documentary focuses on this time in particular, and shows a Maradona perennially in shock at the level of adulation shown him, as he gradually gives more of himself to the nefarious influences around him.

He was openly wooed by the Neapolitan Mafia, the Comorra, and began to unashamedly accept their expensive gifts and invitations to events and openings. It also meant he had an unlimited supply of cocaine. He was arrested in 1991 for soliciting drugs and prostitution.

The series of doping violations that eventually brought his career to a stuttering halt foreshadowed the serious health problems to come.

“I was, am and always will be a drug addict,” he said in 1996.

In 2000 Maradona was hospitalised with a heart condition caused by his cocaine use and moved to Cuba for two years at the invitation of his friend Fidel Castro to undergo rehab.

In 2004 he suffered a heart attack and was forced to have gastric bypass surgery a year later.

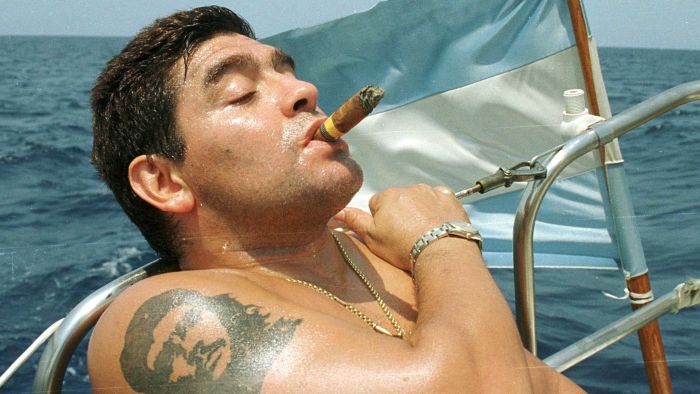

In 2007 he was hospitalised again with the effects of excessive eating, drinking and smoking cigars and in November, 2020 he underwent surgery for a blood clot before checking into rehab afterwards for his alcoholism.

Hounded by the press as he struggled for form and fitness in the lead-up to the 1994 World Cup, Maradona shot at reporters gathered outside the gates of his house with an air rifle, injuring several of them.

It wasn’t the only time he hurt a member of the press corps. When he named his squad as coach for Argentina’s 2010 World Cup campaign, he ran over a cameraman’s leg in his car, then shouted abuse at him as he drove away.

Diego married Claudia Villafañe in 1987 but they divorced in 2003 after numerous infidelities on the part of the footballer. The pair would remain close throughout his life, though and she continued to manage him professionally.

A number of people claiming to be his illegitimate offspring have come forward, but for many years Maradona only acknowledged his two daughters with Villafañe, Gianinna and Dalma.

The Argentine media has reported he may have up to 11 children, with his lawyer recognising in 2019 that Maradona had fathered at least three during his time in Cuba.

The most famous Argentine

Argentine psychologist and author Gustavo Bernstein once said: “Maradona is our maximum term of reference.

“No one embodies our essence better. No one bears our emblem more nobly. To no other … have we offered up so much passion. Argentina is Maradona, Maradona is Argentina.”

Juan Perón, Eva Perón, Formula 1 legend Juan Manuel Fangio, Pope Francis and Lionel Messi are all known across the world, but no Argentine is as recognisable globally, or as adored at home as Diego Armando Maradona.

The debate as to whether he was the greatest footballer of all time will never be decided, it’s certainly true that for a particular generation of fans who remember El Diego in his pomp, nobody else can ever compare.

He fell well short of the God-like status bestowed on him, but the myth of Maradona will live on forever.

Goal of the Century

Loading…

Commentary from Victor Hugo Morales:

Now Maradona has it, two marking him, he dribbles past, taking off down the right, this genius of world football.

He leaves behind a third! And is going to lay it off to Burruchaga, but it’s still Maradona…

Genius! Genius! Genius! Ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta and GOOOOOOOOOOOOL!

GOOOOOOOOOL! I want to cry!

My God, long live football. Incredible goal!

DIEEEEGOOOO! Maradona!

It’s making me cry, I’m sorry.

Maradona, in a memorable run, in a play for the ages.

Cosmic kite, what planet are you from?

To leave so many Englishmen in your wake?

For the country to be a clenched fist, shouting for Argentina.

Argentina 2, England 0. Diego! Diego! Diego Armando Maradona.

Thank you, God, for football, for Maradona, for these tears, for this Argentina 2, England 0.