Second-hand cars, Swedish DIY furniture and printer cartridges certainly weren’t what George Augustus Sala was thinking of when he first coined the phrase “Marvellous Melbourne”.

Visiting Australia in 1885, the well-known London journalist caused a local sensation when he wrote a series of articles raving about the magnificence of Melbourne. Such admiration from an international observer was desperately coveted.

“It is desirable for many reasons that I should explain why I have called Melbourne a marvellous city,” Sala wrote. “The whole city, in short, teems with wealth, even as it does with humanity.”

George August Sala. “The whole city teems with wealth, in short, even as it does with humanity.”

At the time, Melbourne was living large on the excesses of a dizzying land boom. The property binge was being fuelled by British investment and local speculation, while loose credit was extended with confidence after the extraordinary wealth generation of the Victorian gold rush.

Migrants seeking a piece of the action flocked to Melbourne, as the population exploded from 280,000 people in 1880 to 480,000 10 years later. A colonial outpost was transformed into one of the world’s richest cities.

Suddenly, tall buildings to rival those of New York City filled the sky, thanks to the invention of the hydraulic elevator. All around, lavishly decorated banks, hotels and coffee palaces oozed optimism and wealth. Shops stayed open until midnight, with futuristic electric lights illuminating vibrant arcades. The air crackled with new ideas of Darwinism and spiritualism; of the eight-hour work day and women’s rights.

More than a century later, the character of Kath Day-Knight was marvelling at a more outer-suburban golden mile in the TV comedy Kath and Kim. Taking hunky out-of-towner Sandy Freckle on a tour of the delights of Fountain Lakes, she pointed out all the shopping hotspots: Reg Hunt Motors, IKEA, Cartridge World, Barbecues Galore.

“It’s all here in Melbourne,” she beamed. “It’s Marvellous Melbourne.”

Kath might have been taking a dig at the city’s self-regard but she was also illustrating the longevity of Sala’s famous description, as well as its flexibility.

“It’s a phrase that’s hard to kill off,” says historian Graeme Davison, author of The Rise and Fall of Marvellous Melbourne.

“It has a habit of reappearing when we’re on a downer or when things are in the balance. It reinvigorates a sense of civic pride and optimism.”

So what happened after Melbourne became “marvellous”? And how has the nickname persisted through the city’s ups and downs?

The Block, Collins Street. c 1910.Credit:Ward, Lock & Co., State Library Victoria

What was ‘doing the Block’ on Collins Street?

To stroll down Collins Street – including what would later come to be known as the “Paris” end – in the 1880s was to witness a time of great possibility. Local author Fergus Hume captured the scene in his wildly successful detective novel The Mystery of a Hansom Cab in 1886.

The book was a hit in London and the colony, selling more than half a million copies – enough to outpace Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and help forge Melbourne’s growing reputation overseas.

“It was Saturday morning, and of course all fashionable Melbourne was doing the Block. With regard to its ‘Block’, Collins Street corresponds to New York’s Broadway, London’s Regent Street and Rotten Row, and to the Boulevards of Paris,” wrote Hume.

“It is on the Block that people show off their new dresses, bow to their friends, cut their enemies and chatter small talk. The same thing no doubt occurred in the Appian Way, the fashionable street of Imperial Rome.”

As Melbourne faces one of its toughest challenges yet, the current moment is not that different to what happened when the 1880s boom came to a disastrous end. COVID-19 has been eliminated for now, but the pandemic has wrought major damage on the economy. The once-vibrant CBD, what Sala described as a “chessboard city”, is littered with empty shops and closed businesses.

Bourke Street looking west from Swanston in 1916, during World War I.Credit:State Library Victoria

How did Marvellous Melbourne decline?

In the 1890s, a deep depression brought severe unemployment and homelessness as a string of banks and building societies went under. Many of the grand structures built quickly during the rush were left empty, with no one willing to pay the cost to rent them.

“I really see echoes between how the city seems at the moment and how it was then,” says historian Robyn Annear, author of A City Lost & Found: Whelan the Wrecker’s Melbourne.

The man who tore down some of those buildings was Jim Whelan, founder of a demolition firm that would help change the face of Melbourne. During 100 years of operation, Whelan the Wrecker would become synonymous with the city’s evolving character. “It was a really tough time because Melbourne had such a grand idea of itself, but Sydney overtook it after that,” says Annear.

The Royal Exhibition Building, which hosted the opening of the first federal Parliament in 1901. Credit:State Library Victoria

What does Sydney have to do with it?

The rivalry between Melbourne and Sydney has a long history. Sydney was set up as a penal colony while Melbourne saw itself as a free settlement when it was founded in 1835 (although Victoria did take some convicts).

Soon after, the southern city was clearly on top, leading Sydney as Australia’s biggest city from 1861. Even after the bust, Melbourne was chosen as Australia’s first capital after Federation until Canberra was established in 1927.

But by the turn of the century, Sydney had claimed the title of most populous city. It also became the nation’s financial capital and – with its harbour, beaches and climate – offered a dynamism many believed had gone missing from Melbourne.

Melbourne was left to take pride in being everything Sydney wasn’t – the cosmopolitan city that prefers cultural delights over natural beauty.

“That really hurt,” says Annear, “That’s how Melbourne defined itself: ‘we’re not Sydney’. Melbourne went on to be the capital city when Federation came but it wasn’t the same. There was a lot of civic shame and inferiority.”

This us-against-them attitude may even have played out during the COVID-19 lockdown, as Melburnians took a certain kind of pride in going through the ordeal alone.

“I was thinking, yes, this is the kind of nihilism that Victoria feeds on,” says Annear. “There was a strong sense of resentment. I think that has endured, that feeling of being the underdog.”

How did we move on from Marvellous?

Marvellous Melbourne no longer reflected the prevailing mood, and the tagline was replaced in newspapers with less effusive nicknames such as Miserable Melbourne and Murderous Melbourne.

There was also Marvellous Smellbourne to reflect the noxious odours being produced by the city’s abattoirs, tanneries and factories. Before mass sanitation, the Yarra was an open sewer. Melbourne’s famous laneways were used to cart “night soil”, a euphemism for human waste.

For a while, Sala’s words acted as a cautionary tale of a city that got swept up in greed. The boast became a target for parody – a satire, Juvenal in Melbourne, lampooned the city’s hubris.

“Hers is a people ever in extremes, or in a nightmare, or in golden dreams,” wrote the satirist, Henry Lingham, in 1892.

Then the slogan was mostly forgotten, swept away and confined to history, as the city lived through another boom before the crash of the Great Depression in the 1930s. But a generation later it started to appear again.

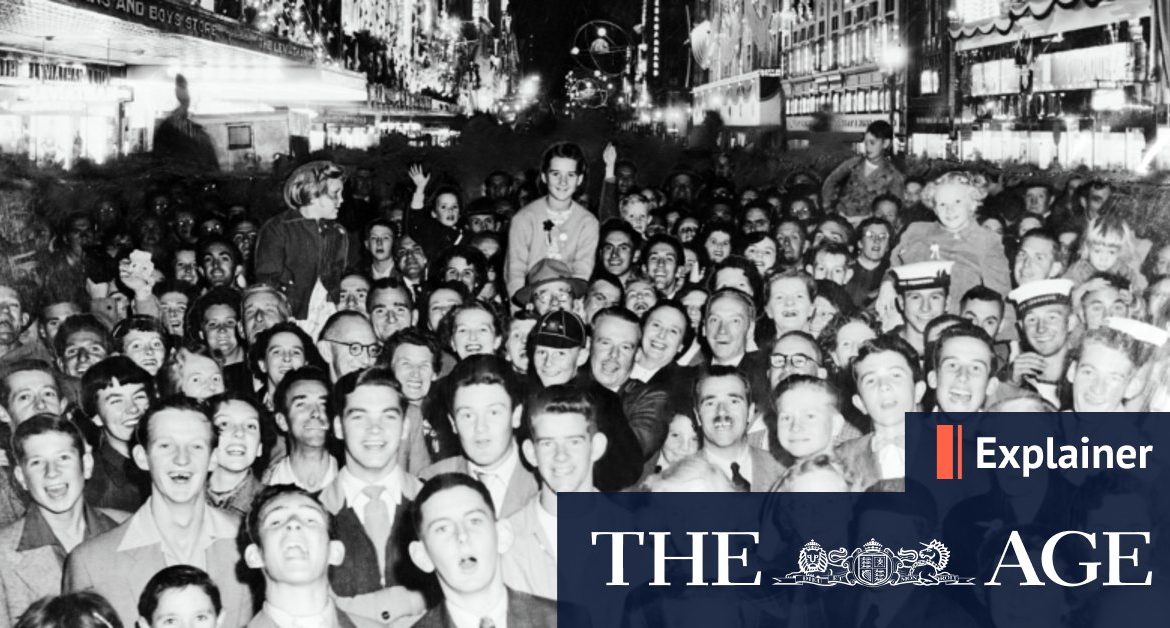

Tens of thousands of Melburninans turned out to see a light show for the Queen’s tour in 1954.Credit:Fairfax

How did Melbourne become a modern city?

In 1954, as the Queen and Prince Philip boarded a Qantas plane at Essendon Airport in front of 10,000 people after a triumphant tour, there was a fresh optimism in the air. People were moving to the suburbs to enjoy the benefits of sustained economic growth.

On Bourke Street, Italian migrants were installing one of the city’s first espresso machines, shipped from the old country to a cafe called Pellegrini’s. The arrival of coffee culture would eventually lead to Melbourne exporting its own style of cafes and coffee-making, particularly the flat white, back around the world.

Queen Elizabeth and Prince Phillip wave to crowds at Essendon Airport in 1954.Credit:Fairfax Media

Speaking in front of the royals, lord mayor Robert Solly recalled a saying that had been popular when he was a young man, at the start of the century. It was, of course, Marvellous Melbourne.

“Now, 40 years later, there is no more fitting title for our city and its people,” he said.

Two years later, the Olympics sparked a rush for Melbourne to reinvent itself as a modern city. That resulted in the wrecking ball being put through many of the grand buildings still left from the 1880s – decisions now looked upon with regret, even though such an attitude was seen as old-fashioned at the time.

“Things we see as so distinctly Melbourne were really on the table to be done away with in the ’50s,” says Annear. “Victorian-era stuff was on the nose, it was old enough to be shabby but not old enough to be treasured.”

The city managed to save its trams, at serious risk of being replaced by cars and buses. Now they are intrinsically linked to Melbourne’s identity (even though many other cities around the world have them).

The opposite happened in Sydney, which ripped up its tram network in the 1950s. Recently, a light rail line was rebuilt through its CBD at great expense.

A Communist Party take on the Marvellous Melbourne idea.

When did Marvellous Melbourne make a comeback?

The reclamation of the slogan started in the 1980s, as people began to look back at what the city had been like 100 years earlier.

A comedy troupe wrote a musical called Marvellous Melbourne: Back to Bourke Street while the Communist Party published a manifesto in 1985 called Make Melbourne Marvellous! (their main idea was to nationalise the car industry in favour of public transport).

Soon it was a rallying cry to breathe life back into Victoria’s capital after the collapse of the State Bank and the subsequent recession of the 1990s. In Sydney, newspapers were making jibes that Melbourne had fallen once again.

It was during that decade that the inner city was revitalised, as a relaxation of licensing laws created something else Melburnians would claim as their own: the laneway bar. Migration from all parts of the world, particularly Asia, gave the city an international feel. Rather than being deserted by office workers after 5pm, a nightlife reminiscent of Sala’s era returned to the city.

That would lead to another crown: world’s most liveable city. During the 2010s, The Economist magazine awarded Melbourne the title of most liveable city seven years in a row. For boastful politicians, it was like being called “Marvellous Melbourne” all over again.

Laneway culture became a Melbourne calling card.Credit:Rebecca Hallas

Are we Marvellous now?

With experts predicting that Melbourne will overtake Sydney’s population some time this decade, there are further reverberations back to the 1880s. Before the pandemic, both cities were expected to reach 6 million people by mid-2026, with Melbourne then pushing ahead. Sydney’s harbour and geography, once seen as natural advantages, are now viewed as limiting factors for growth.

But as it did in the 1880s, Melbourne’s increasing population has put a strain on housing, transport and services. Many would argue that uncontrolled growth is neither marvellous nor particularly liveable.

It’s unclear what lasting effect the pandemic will have on Melbourne’s growth, particularly in the CBD. Only 25 per cent of workers are currently allowed to return to office buildings, while some may never come back at all. The era of work from home has begun, meaning there is likely to be less population density in the future. Overseas travellers are still months away from returning, as are international students.

One potential effect is that the vibrancy will move to the suburbs, with people staying closer to home – a throwback to the 1950s, when cars were king. It might be quieter than Sala’s idea of Melbourne, but Kath Day-Knight in Fountain Lakes would approve.

While Marvellous Melbourne is enshrined in the lexicon of advertising and public relations, Davison says the city that Sala first described had “something in the air, something in the quality of life and a sense of excitement”.

“The city seemed to have a vibrancy and dynamism that they didn’t find elsewhere in Australia,” he says.

“When people still use it they’re probably feeling for those similar qualities.”

“It’s all here in Melbourne”: the cast of Kath and Kim, with character Kath Day-Night in the centre, in 2003. Credit:ABC TV

Tom Cowie is a journalist at The Age covering general news.

Most Viewed in National

Loading