On May 31, 2020, a sea of people filled the streets of the Fairfax District in Los Angeles. Five police helicopters circled above their heads. Two LAPD squad cars were set alight and burned.

Days earlier, the world had watched George Floyd take his last breaths. Now emotions reached boiling point — anger expressed in a cacophony of dissent. Riot police arrived with rubber bullets, batons and tear gas.

Played through car windows and chanted by the crowd was the anthem of the uprising, YG and Nipsey Hussle’s ‘FDT’: “F*** Donald Trump!”

Two hundred metres away, a 33-year-old man and his wife anxiously peered out their window, their one-year-old son playing with a toy truck. In the days that followed, they would join the crowds on the streets of LA, demanding an end to the dehumanisation of black lives.

In another time, the man achieved fame as a sporting champion in a foreign land — an All-Australian footballer, a premiership hero of the Collingwood Football Club. Now he marched upright, a bandana shielding his face from the pandemic sweeping the planet, a Congolese flag draped over his shoulders.

“Their lives are amongst the least valued on earth. US foreign policy has caused death and destruction to tens of millions of black lives in the Congo, and despite the insurmountable pain that has been inflicted on Congolese, they have never stopped fighting for their own liberation.”

To understand the circular route that led Lumumba to where he stood that day, it helps to know where he comes from in Brazil — a place the locals still call ‘Little Africa’.

“I was born on the sacred indigenous lands of the Guarani, in a quaint little hospital that sits on top of a former harbour area, which was built as a port for the arrival of enslaved Africans,” Lumumba says.

“The wharf where they first touched down is known as Cais do Valongo, about 50 metres from the hospital. It’s considered the most important physical evidence of enslaved Africans’ arrival on the American continent.”

For close to six decades in the 19th century, Cais do Valongo was a place where an estimated 900,000 women, men and children began their existence in the “new world” by being trafficked into slavery.

Those who escaped slavery formed communities throughout Rio’s mountainous terrain, called quilombos — places of refuge for Africans.

Lumumba’s cultural origins start within a Quilombo community called Jongo Bassan da Serrinha, situated in Madureira, Rio’s North zone.

“I come from a powerful, matrifocal community in Rio de Janeiro, where our cultural tradition, known as Jongo, has been well preserved,” Lumumba says.

“In Brazil, a black youth is killed every 23 minutes. Police kill black people at a rate that’s 17 times higher than that of the USA. My mother was a tireless campaigner for what our community calls ‘cultural resistance’ — the act of fighting oppression through culture. Maintaining the connection to traditions is one defence against the ongoing genocide that is being waged against Afro-Brazilians as a whole.”

It was the beating of drums that drew Lumumba’s parents together.

“Drums sit at the intersection of the physical and spiritual worlds,” Lumumba says.

“They are sacred for their power to establish a direct connection to our ancestors.

“My father was a new arrival in Brazil, seeking asylum from a brutal civil war in Angola. During an event for Brazil’s ‘black consciousness’ week, he was performing a traditional Kongolese dance.

“His performance caught the eye of the Jongo Bassan da Serrinha community, which my mother was a part of.”

A 500-year struggle

In December 2013, the man in Collingwood’s number eight guernsey quietly appraised a year of unprecedented turmoil, steeling himself to stride over a symbolic threshold.

“This is the only way forward,” he told himself. “You can’t turn back from this moment. You can’t. You’ve just got to keep going forward with it.”

Until December 2013, the football world had known him as Harry O’Brien, an AFL star with a social conscience and big ideas. He was a unique figure in the game, unafraid of standing apart.

He knew himself by his birth name: Heritier Lumumba.

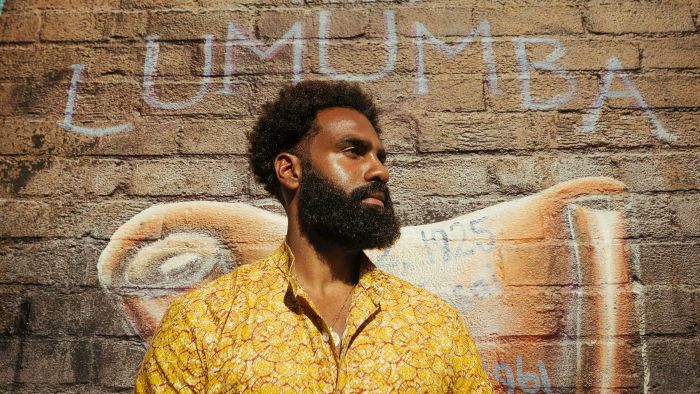

In December 2013, Lumumba didn’t change his name, he corrected it. It was the most powerful gesture in what he sees as a lifelong process of decolonisation. He says his name now lies at the heart of his identity, reconnecting him with Africa, giving him strength in a world that has historically abused and undermined his people.

Reclaiming it punctuated the year in which everything changed. It was the moment Lumumba stopped playing peacemaker and called out Collingwood’s culture of discrimination by confronting Magpies president Eddie McGuire, the man whose name still symbolises the Collingwood that Lumumba once loved.

“I knew that I had to do it,” Lumumba says.

Seven months earlier, during the AFL’s Indigenous round, a 13-year-old Collingwood supporter had labelled Sydney’s Indigenous champion Adam Goodes an “ape”, sparking a national furore that was exacerbated when McGuire made his immortally offensive joke, likening Goodes to King Kong. Lumumba had been among his harshest critics; on live television, he had schooled McGuire in the basics of racism.

McGuire accepted his penance, but behind closed doors at Collingwood, Lumumba says he was made to feel a pariah, undermined by the club and mauled by the press.

When Lumumba arrived on the AFL scene at the end of 2004, much was made of his Brazilian nationality but little of his African ethnicity. Today, he uses a one-word description of himself: African.

“I understand the strength of belonging to the Bakongo people,” Lumumba says.

“It directly connects me to a 500-year worldwide resistance to white power and oppression. My name is a symbol of black power and revolution, and ties me to the spirit of great men such as Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali and Patrice Lumumba, the father of Congolese independence, who was martyred in the name of Pan-Africanism.”

The seed had been sown long before 2013. In his travels through the African diaspora and continent. In the AFL arenas where Lumumba was heckled and abused. In the streets of Collingwood. In rooms full of white footballers, white coaches and white journalists, who stared blankly or snickered when Lumumba held up a mirror to prejudices long accepted as part and parcel of the hairy-chested AFL culture — prejudices he says were ingrained at Collingwood.

“Central to this, we have all been subjected to centuries of anti-African indoctrination,” Lumumba says.

Distant from Collingwood and the AFL, far removed from whatever sense of home he once felt in Australia, Lumumba now lives in South Los Angeles. There, he says, he feels a greater sense of belonging.

“A large percentage of African-Americans descend from the Kongo Kingdom,” he says.

“We come from the same people, and it feels like I’m with family here. Also, my maternal ancestors are native to the Americas, just like many people in Los Angeles. I’m proud to be on Tongva land.”

It’s a long way removed from his school days in Perth, when few could be bothered learning his name. In those days, he was known as Harry instead.

“Lumumba, to me, sounds like the beating of a drum,” he says.

“LU-MUM-BA. It’s rhythmic. It has a powerful vibration. No matter where I am in the world, I stand taller when people of African descent say it. I feel empowered knowing that my name can connect them to their indigenous tongue’s natural intonation. It means something to people here. They’re proud to pronounce it.

“It’s a stark contrast to when I was playing football and being called ‘chimp’ on a daily basis, isn’t it?”

‘The truth they already know’

So often has the epithet “chimp” been used in discussions of Heritier Lumumba in the last four years, its power to shock is diminished. This stain on Collingwood’s reputation was first revealed in Jeff Daniels’s 2017 documentary, Fair Game.

For those projecting Collingwood’s public front, and a titillated media, it has become an obsession.

“It’s very reductionist and discriminatory,” Lumumba says.

“Keeping the focus on whether or not the nickname was used has been a distraction from the real problem and from the impact it has had on me.”

“I’ve never heard it,” McGuire said in June.

“The only mouth I have heard that nickname out of was Heritier’s himself when he told me about it,” said Collingwood coach Nathan Buckley, once Lumumba’s football mentor.

Yet Lumumba’s experiences have been corroborated by six of his teammates. Andrew Krakouer, Leon Davis, Chris Dawes, Chris Egan, Brent Macaffer and Shae McNamara have all registered public support. Others look on in silence.

“They bit their tongue and that’s what they have to live with for the rest of their life,” McNamara told Seven News in June.

Living with it too is the AFL. Normally eager to affirm the league’s progressive bona fides, chief executive Gillon McLachlan has been wishy-washy on Lumumba’s case. After Fair Game aired, McLachlan was on the front foot.

“Our industry has been a leader in the country on racism,” he said.

“We’re all on a journey to do the best we can, but I think our history is pretty strong.”

Yet McLachlan also cast doubt on Lumumba’s mental health: “With respect to Collingwood — I know Tanya [Hosch, AFL’s general manager of inclusion and social policy] has met with Heritier — this issue is really about where he’s at, and his state of mind and his welfare.”

Lumumba says: “His [McLachlan’s] response was a template straight from the playbook that many institutions deploy. Deflect attention away from the underlying problem by evoking the ‘crazy black’ stereotype.”

In June, it was announced that Lumumba’s time at Collingwood would finally be subjected to something more rigorous than media analysis — a ‘review’ commissioned by Collingwood itself and carried out by Eualeyai/Kamillaroi woman Larissa Behrendt, professor of law and director of research at the Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning at the University of Technology Sydney.

Yet Behrendt has no investigative powers. An investigation would in any case have required the cooperation of Lumumba and those who were at Collingwood in his time but have since left; Lumumba, among others, would not consent to an interview.

The ABC sought responses from Collingwood president Eddie McGuire and coach Nathan Buckley to a series of questions related to Lumumba’s experiences at the club.

“We are looking forward to the arrival of Professor Behrendt’s report and the opportunity it presents to inform Collingwood’s future,” a Collingwood spokesman replied.

“As previously outlined, the club will be sharing publicly the findings of the report but until such time as it can do so will not be making further comment.”

Lumumba’s reaction to the review’s announcement was unequivocal: “I have no desire to convince Collingwood of a truth they already know,” he tweeted on June 24.

“Given the club’s inability to come clean, and the way it has attempted to publicly and privately attack my reputation, I cannot accept this ‘integrity’ process has been proposed in good faith.”

On one hand, it begged the question as to what faults Behrendt was expected to find. On another, it presented a paradoxical vulnerability for Collingwood: what happened if Behrendt, reliant on those driving the supposedly improved atmosphere at the club, still uncovered examples of the toxic, discriminatory and bullying culture Lumumba laid bare?

Watching from afar, Lumumba thought of Collingwood’s common refrain after Fair Game’s release, when key figures always claimed to be “reaching out” to him. It made him think a year further back, to the bewildering period when concussion forced him into AFL retirement.

“I didn’t get one message or email from the Collingwood Football club,” he says.

“They could easily have said, ‘Yeah, we messed up’,” Lumumba says.

“Instead they’ve doubled down on their denials and attacks. They have had many chances to get on the right side of history. But as far as I’m concerned, it’s clear what the club’s position is.

“When people are in positions of power, yet have not taken the necessary steps to unlearn and deprogram a history of racist indoctrination, the decisions they make are dangerous. Their prejudices and biases expose others to major harm. This needs to be urgently addressed within the AFL industry.”

As the review progresses, Lumumba anticipates more of the lurid counter-narratives propagated since 2014 by Collingwood’s powerful PR machine. “Heritier Lumumba gave permission for Scott Pendlebury to call him ‘Chimp’ while at Collingwood,” read a Fox Sports headline in August.

“No-one spoke to me in relation to this article,” Pendlebury tweeted in response.

“Click bait. There is an independent review into the time in question. I will respect it.”

And the media has gone on being receptive.

‘Too precious, too sensitive’

The first time Lumumba was written about in a Melbourne newspaper, it was December 2004. He was 18 years old and adjusting to life on the Collingwood rookie list. The Sunday Age article announcing his arrival began: “Harry O’Brien could have been playing soccer for Brazil. He also could have been scratching for a living on the streets of Rio de Janeiro’s notorious slums.”

Back then, Lumumba kept it in a scrapbook with many like it, reinforcing that his childhood dream was coming true. But 16 years later, those opening lines stick in his mind as a taster of what was to come.

“This is what the Australian media does to people of African descent,” Lumumba says.

“They love to use descriptors like ‘war-torn’ to describe our homelands, or focus on the extreme poverty in our countries, instead of telling the full story — that centuries of oppression and exploitation by Europeans has created those conditions.

“Clearly, most Australian journalists don’t understand this. They have been taught since early childhood that black people are inferior, which is why they consistently reinforce damaging stereotypes of us.”

To sift through the hundreds of thousands of words written and spoken about Lumumba is to understand his conviction that the AFL, Collingwood and a co-dependent media combined to create the damaging public personas by which he is known: the egotist who craves attention; the shady opportunist looking for a pay-out; the crazy black man with an axe to grind.

It wasn’t always that way. The AFL press of Lumumba’s early career mostly saw him and his burgeoning social conscience as a welcome novelty in the homogenised pool of cliché-peddling players and coaches.

Back when Lumumba was only highlighting societal problems in the abstract, reporters called him “worldly”, “deep thinking”, “level-headed” and “well liked”. He was an “infectious character”, a “role model”, “a leader”, and that highest of compliments in the Melbourne footy world: a “great bloke”.

Fast-forward to a single fortnight of 2014, by which point Lumumba had finally attacked the AFL’s myths of equality and tolerance. Now he was “angry”, “disgruntled”, “disaffected”, “dramatic”, “unhappy” and “high-maintenance”. He’d become a “moral crusader”, a “non-conformist”, “a hindrance”, “a handful”, a “strange cat”, “offended for others” because he “lacks a filter”, forever taking “the high moral ground”.

By 2014, Heritier Lumumba had become the opposite of a great bloke: “Too precious, too sensitive, too much work” said a Herald Sun headline.

Journalists who had once welcomed his openness now sneered at Lumumba’s “broken family”, simultaneously prying for their darkest secrets. Lies appeared about everything from his holiday plans and mental health to his confrontation of issues as serious as suicide and sexual abuse.

And the betrayals were many. One journalist invented provocative quotes and attributed them to Lumumba, used damaging information he’d shared off the record, then ignored Lumumba’s phone calls when he wanted to discuss the misinformation and the subsequent fallout that enveloped him.

There were the newspapermen who talked over him every time he opened his mouth. There was the highly publicised debacle on The Project, after which Lumumba claimed the program’s presenters had colluded with Collingwood.

“The documentary was effective, but I thought The Project would be an opportunity to finally put my story forward on a mainstream platform,” Lumumba says.

“That interview killed all the momentum that had started to build around my story.”

Lumumba says one TV reporter engaged him in a long and meandering conversation, then presented an edited interview that made it sound like Lumumba had not returned from a concussion — an injury that would end his career — because he was still mourning the death of Muhammad Ali.

“There were tens of millions of people around the world who were mourning the death of Muhammad Ali,” Lumumba says.

“He means so much to black people because he fought and sacrificed for us. The way I was targeted for simply mentioning Ali’s significance to me was yet another example of how the culture attacks black identity.

“They painted me with the centuries-old stereotype of the crazy black man, when in fact it is them who suffer from the psychosis of white supremacy.

“Most people who reported on my life were ill-equipped. The cultural competency was and still is shocking. That causes a lot of damage and halts the progression of society.

Lumumba says only a few reporters treated him with dignity and respect. The standouts were SBS journalist Ahmed Yussuf, who could empathise from his own experiences as an African-Australian; Jo Chandler, for her sincerity and for not coming from the sports world; and the late Trevor Grant, by then an ex-football journalist. Grant pressed a copy of Eduardo Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America into Lumumba’s hands and later wrote in The Age:

“The highly paid image-makers project the AFL as a broad, enlightened church, free of the bigotry of the past. But, really, it is like any other corporate environment in pursuit of a singular aim, and therefore unable to accommodate anyone who dares to step outside its rigid parameters. … [Lumumba’s] capacity to speak his mind with stunning clarity is so rare in football that it struggles to deal with it.”

Between two worlds

Lumumba says he was three months into life as an AFL player when the racist jokes began — on training grounds, in locker rooms and anywhere else that Collingwood players gathered en masse.

In those early years, his escapes were the company of Melbourne’s Afro-Brazilian community, and a pastime of which few at Collingwood were aware: he was a percussionist in two samba bands, forging deep connections with his culture.

“It was a refuge for me while I was playing football in those early years,” Lumumba says.

“I was able to freely express myself through dance, percussion and singing without the overbearing presence of the white gaze.

In the suffocating world at Collingwood, he says a teammate frequently used the word “ni***r” at the top of his voice. Another bought a black dog and named it after Lumumba. In time, he says he would also be called “black c***” and “slave” in the name of humour. By his second season, he says the dehumanising “Chimp” nickname took hold.

Why didn’t he put a stop it there and then? Consider the burden on a black teenager within a powerful white institution. Consider Lumumba’s status in Collingwood’s pecking order. As their final selection in the rookie draft of 2004, he was Collingwood’s most expendable player.

“I always had the mentality that I could upset the club in some way and lose my spot,” Lumumba says.

“What that did was make me very much about following orders and instructions. When I did media, they’d say ‘you can talk about this, you can’t talk about that’, and I’d basically promote the image of the AFL and the football club.

“Within that paradigm, being black combined with challenging the pre-existing culture would have meant really going against the grain. I felt a level of isolation in those early days, but it seemed even more isolating and tiresome to constantly speak up.”

As a player, he made strides as the type of team-first, lockdown defender his first coach Mick Malthouse cherished. Hard-working and athletically gifted, Lumumba shadowed his teammate and early football mentor Nathan Buckley, developing habits that would eventually make him the hardest trainer at Collingwood.

Lumumba was also soon among the most electrifying defenders in the game, peeling off his man and sprinting forward — moments of athletic flair that are the lasting image of his football brilliance. And he commanded respect. When Lumumba was 23, Malthouse labelled him a “future captain”.

In his football, support and mentorship came from the likes of Paul Licuria, James Clement, Marty Girvan, Scott Watters and David Buttifant.

“I was fortunate that there were people who really cared about my success, and invested so much time and energy into me,” Lumumba says.

From day one, he was also among Collingwood’s greatest marketing assets — photographed as often as any other Pie, front and centre in advertising campaigns, hosting club videos and commanding the ‘Harry’s World’ section of the Collingwood website. In 2005, before he’d even established himself as a player, Lumumba became the AFL’s inaugural multicultural ambassador, tackling with gusto his duty to broaden the game’s appeal to migrant communities.

His response to the hyper-masculinity and white monoculture informing Collingwood’s playing group was to disappear in the off-season and travel through the Americas, the Caribbean and the African continent, connecting with their people and cultures, forever wanting more.

“I began to understand that I belonged to a global people,” Lumumba says.

At Collingwood, he focused on survival. He calls it his “go along to get along” phase. One coping mechanism was an “assimilationist” mindset. Reporters lapped up his praise of the Anzac spirit and grateful, English-speaking migrants.

“I’m just another Australian kid who wants to play AFL,” he told The Herald Sun in 2006.

But his silent discomfort continued. One night, he says he was ambushed by two security guards at Collingwood’s training facility and had his parking pass forcibly removed from his hands, trapping him in the carpark until a teammate returned from home to let him out. When Lumumba complained, he says the club did nothing.

In one game, an opponent called Lumumba a “f***ing Golliwog” but he didn’t feel confident enough to report the abuse.

Every year, the team’s AFL-mandated “respect and responsibility” training sessions would roll around and Lumumba was reminded why some colleagues were so comfortable in their prejudices: the one-hour briefings included a desultory 15-minute discussion of racism.

On-field, Lumumba confirmed his rise to star status in 2010, when was named an All-Australian and Collingwood broke through for its first premiership in 20 years. But it was also the season that his problems with the media intensified.

News that US President Barack Obama would soon visit Australia prompted Lumumba to fire off an email to Nick Hatzoglou, then head of the AFL’s multicultural programs. If the rumours were true that Obama would attend an AFL game or event, Lumumba said he desperately wanted to be there.

He’d devoured Obama’s memoir, Dreams From My Father, and been struck by his and Obama’s common experiences.

“We grew up as black children who were outsiders in isolated capital cities; our fathers African; Barack was whitewashed to Barry, Heritier to Harry. I felt this profound connection,” Lumumba says.

Impressed by Lumumba’s passion, Hatzoglou forwarded the email to AFL colleagues, but it was leaked to Herald Sun chief football writer Mike Sheahan, who was soon on the phone to a startled Lumumba. The resultant front page article seemed like something quirky on a slow news day — all the better with news from AFL headquarters that chief executive Andrew Demetriou had escalated the request to Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

Yet in the blink of an eye, Lumumba’s profound connection was a public humiliation. Other media erroneously claimed Lumumba had presented Rudd with a list of demands. He was taunted by fans and targeted with physical attacks by opposition players. The story became a running gag. “I want to meet Obama too,” said a reader letter in the Herald Sun. “What makes you so special?”

“That is when I really began to notice the tone shifting a lot,” Lumumba says.

By the end of 2011, every Collingwood player was entering another paradigm: after narrowly missing back-to-back flags, Malthouse honoured his agreement to a coaching succession plan and reluctantly handed the reins to Buckley. Crises loomed. Lumumba had secured the fifth in what would end up eight consecutive top-10 finishes in the club best and fairest award, but he was still labelled “the poster boy for Collingwood’s decline”.

None of the insults could prepare him for the events of 2013.

A line in the sand

May 29, 2013 was the day everything changed for Heritier Lumumba.

Soon after McGuire’s comments on Goodes landed with a calamitous thud, Lumumba tweeted: “It doesn’t matter if you are a school teacher, a doctor or even the president of football club I will not tolerate racism, nor should we as a society. I’m extremely disappointed with Eddie’s comments and do not care what position he holds, I disagree with what came out his mouth this morning on radio. To me, Eddie’s comments are reflective of common attitudes that we as a society face.”

When Lumumba said he wanted to publish a tweet, as per club policy, he was given approval by senior staff in lieu of calling McGuire directly. In fact, five minutes later, McGuire called Lumumba angrily. The senior staff now distanced themselves from their approval.

The pair convened on Fox Footy’s AFL360, Lumumba talking passionately about casual racism, and the distinction between direct and indirect racism — insidious abuses often “hidden under larrikinism” in Australia, by which some might have read Collingwood.

Publicly, McGuire accepted the criticism. Publicly, Buckley said Lumumba and the only other black player on the team, Krakouer, could skip the next weekend’s game with the club’s support if it was “not within them” to play.

Privately, the pair were pressured into playing, as Krakouer later admitted: “I was urged by the coaches to fly to Brisbane and play against my wishes, because I was told it would be seen as a statement against Eddie and the club.”

Support, instead, flocked to the president. “The person who is being hated at the moment is actually Eddie,” Buckley told reporters.

Certain layers of context are essential to understanding how Lumumba’s confrontation of McGuire led to his exile from Collingwood and estrangement from the game. The first and most obvious was the catalogue of personal abuses he says he’d weathered at Collingwood — racist nicknames, discrimination and jokes that he says proliferated within the club’s environment.

Lumumba says the second was the punishment he received once he challenged the club’s apparent toxicity. The third was the AFL and the AFLPA’s capacity to effectively deal with racism, something Lumumba doubted after observing their handling of other players’ complaint, particularly those of Gold Coast’s Joel Wilkinson.

In the 2012 post-season, Lumumba had travelled to Brazil again, seeking the counsel of his Jongueiro elders. Imbued with greater purpose and committed to finally drawing a line in the sand, he returned to Collingwood and began his most intense and transformative pre-season training regime yet.

He also freed himself from distractions, investing financially and philosophically in his training and recovery, significantly improving his performance. At his own expense, he hired a full-time assistant, a massage therapist, a chef to create a specially formulated diet and, later, a personal coach who specialised in conflict resolution. As in five of the previous six years, his peers elected him to Collingwood’s 2013 leadership group.

Yet by the time the McGuire controversy engulfed him, Lumumba had still not confronted his teammates as he’d hoped to. After the McGuire incident in May, Lumumba says Collingwood didn’t see fit to further educate its players. He says the racist jokes and ideas continued. He developed anxiety, struggling to sleep; a three-day Gaia retreat during Collingwood’s mid-season bye didn’t halt his spiral.

By late June, Lumumba says, “I began to feel an intense emptiness. I spent time looking into science-based research on the compound psilocybin (derived from ‘magic mushrooms’). I discovered there’s been great success in using it as a treatment for mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress.”

Later, Lumumba’s use of psilocybin became another cudgel for his critics.

“Opioids are highly accessible and widely used in the AFL. During my career, I was aware of many cases of overuse and dependency by players throughout the league, which is highly dangerous.” Lumumba says.

“The outcome of my psilocybin experience was a profound realisation of my obligation to confront the issues at the root of my symptoms.”

By June 26, Lumumba had reached his limit. After words of warning to Buckley and other leaders, he stood before the team and finally tore off the scab, sharing his personal history, explaining his discomfiture with not only the racist joking but the homophobic use of terms like “poofter”, “f****t” and “homo”.

To Lumumba’s relief, the “Chimp” nickname was banished.

Six days later, in another team meeting, a crass joke was made by a member of the coaching staff about one of Lumumba’s teammates looking like a lesbian. As an awkward silence fell over the room, Lumumba says Buckley turned to him and asked whether the joke was OK with him. Lumumba was not quiet about letting his humiliation be known and immediately left the room, then paced laps of Collingwood’s training ground to cool off. He said he would not return until Buckley apologised.

Lumumba’s non-attendance at the next day’s training session ensured non-selection for the club’s Friday-night clash with Carlton. Officially, the Pies cited a floating bone in Lumumba’s ankle as the reason for his omission from the team.

“Things that happen inside the Westpac Centre stay inside the Westpac Centre and probably we’ve been too open in the past,” McGuire told Fox Footy.

Yet word-perfect accounts of the meeting-room argument were soon splashed across Melbourne newspapers. Lumumba skipped town for a few days. Upon his return, it took an eight-hour meeting with the club to end the impasse, Lumumba again explaining fundamental concepts of racism and its impact on him, and the impact of homophobic slurs on the club’s gay staff members. Lumumba says there was a sting in the tail: he was removed from the leadership group.

The media commentary that came in the wake of what became known as the “Lez” incident was savage. “[Lumumba] needs to pull his head in,” began one excoriation. “You have to wonder if [his] issue is not with Buckley, but with himself … maybe the apology should be [Lumumba] to Buckley, and not the other way round.”

Others painted Lumumba like a dog at heel: “Collingwood has dramatically won the feud with rebel [Lumumba] after demanding he return to the club today on its hard-line terms. [He] will train with the Pies at 10:00am but has been told in no uncertain terms to keep his emotional outbursts in check.”

Now Lumumba was “erratic”, “disgruntled”, “troubled”, “bizarre”, “outspoken”, “fragile”, “rogue”, a “sook” and a “destabilising influence” with “serious issues”. He “preached to his teammates” with his “histrionics and screaming matches”, and an “individualism” that was “hijacking the club agenda”.

Later, he would hear the same words from the mouths of club staff.

Buckley, meanwhile, “emerged from a firestorm looking like the only calm, measured man in the room”. Following an indiscreet press conference — “I get the impression that everyone thinks he’s a basket case,” the coach said at one point — he was hailed by the football press for “a Buckley masterclass”.

For Lumumba, there was no let-up. On the Sunday Footy Show, teammate Travis Cloke was asked whether Lumumba needed to “harden up”. Pies football strategist Rodney Eade declared: “The club is bigger than any individual. The club comes first.” Collingwood great Tony Shaw demanded Lumumba be ruled out of contention for the following game due to his impertinence.

But couldn’t Eade and Shaw also have concluded the opposite? At Buckley’s urging, Collingwood of 2012-13 operated under the Leading Teams model of organisational change, a key pillar of which is to “call out” bad behaviours. What was Lumumba’s confrontation of the club’s culture if not that?

“We were being trained to give direct and immediate feedback to players and coaches around actions and behaviours that were in conflict with our values,” Lumumba says.

“One value was community — that was through the whole club. And that’s exactly what I was upholding.”

By day eight of the saga, Lumumba was weighed down by the club’s betrayals and the media’s relentless character assassinations. He was desperate for both to end. He arrived at Collingwood’s training facility, spotted TV reporters and knew why they were there.

“It felt like vultures circling around a carcass,” Lumumba says.

Out of desperation to end the media barrage and unwilling to further inflame the story by placing the blame on Collingwood, he fronted the press and revealed “significant personal demons”. In reality, he says it was his only option to shield himself against significant personal attacks.

“This is my personal experience and I have to do this in the public eye and it’s really tough,” Lumumba told reporters.

“Whatever you guys have been reporting, that’s secondary. This is my real stuff, and the club’s been fantastic in supporting me and protecting me and they’ve tried to do that.”

When he said the last line, Lumumba knew the opposite was true.

‘Side by side we stick together’

In Lumumba’s time, Collingwood coaches cherry-picked team mottos from the club’s history. “Side by side they stick together, to uphold the Magpies name” goes the team song. ‘Side by side’ became Collingwood’s creed. It meant all things ‘team’: solidarity, fraternity, supporting your mate. So firmly did it lodge in the consciousness of players, Lumumba would eventually reference it in his farewell speech.

It had darker undertones too. Lumumba says it was eventually used by the club to silence him. In Fair Game, he explained Collingwood’s reaction when he called out McGuire: “Employees, decision-makers identified that I had gone away from the club’s virtue of ‘side by side’.”

It also featured in Buckley’s conditional support amid the “Lez” furore, after Lumumba’s impromptu press conference: “We are a ‘side by side’ club that provides for all individuals so long as those individuals are prepared to be side by side with the club,” Buckley told reporters.

Lumumba still had two years to run on his Collingwood contract as the 2014 season dawned. His 2013 pre-season training regime had been intense, but now he pushed his body to higher levels. It produced the kind of form that would eventually secure him another top-five finish in the club’s best and fairest award.

Trouble, however, was brewing. At the worst possible time for Lumumba, Collingwood’s form nose-dived and the club’s atmosphere darkened. Club staff continued to confide in him about their difficulties with the homophobia around them, including an offensive poster allegedly made by a player and hung in a common area.

Lumumba’s final act at Collingwood would be a stand on behalf of others. He ripped down the poster and reported it to the club. But not only was no action taken, Lumumba was told that if he felt so passionately about it, he should address it with the players himself.

Lumumba had a year to run on his Collingwood contract at that that point. He told senior football staff he’d rather retire on 199 games than play for another club. Yet word got out, as word has a way of doing at Collingwood, that Lumumba’s future was clouded.

“See ya later,” chortled Tony Shaw on Fox Footy. “Gone. Dusted.”

In October 2014, following another torrent of attacks on his character in the press, Lumumba was officially traded to Melbourne. To Collingwood, he would never return.

In the years since, his story has made a sham of Collingwood’s self-made image of solidarity. When Fair Game was released in 2017, The Age ran an article portraying a culture of fragile egos and moral cowardice.

“The club is defensive and angry,” Caroline Wilson wrote.

“Players past and present privately threaten retribution. Allegations about Lumumba’s bad habits have been made. Many players say they no longer have a relationship with him. He is portrayed as an outcast.”

Many naturally wondered: would those have been the same players who kept voting Lumumba into the club’s leadership group? Did none have the courage to put his name next to such defamatory criticisms? What stock should be placed in the moralising of men whose idea of fun was to call their colleagues poofters, homos, slaves and chimps?

One thing is certain: nobody lived the Collingwood ideal more earnestly than Heritier Lumumba, taking to heart the club’s origin story as a beacon of hope to the impoverished underclasses of Collingwood — the gritty inner-northern suburb in which Lumumba alone among Pies players chose to make his home.

At first, the thing he enjoyed most about living in Collingwood was looking up at the Fitzroy commission flats he’d lived in as a young refugee. Then he came to love the melting pot of cultures and creeds and the daily parade of humanity in all its forms.

Only once could he coax a group of teammates down Smith Street, with its hodgepodge of dive bars and art galleries. Some said they felt unsafe. But what they found confronting about Collingwood, Lumumba found comforting — a sense of community and an acceptance of differences.

It was, in other words, many of the things its footballing namesake was not.

‘The gifted prince’

At times in the last decade, Heritier Lumumba has been bracketed with Adam Goodes. After all, their courageous stands intersected and bore similar hallmarks: proud black men highlighting uncomfortable truths and paying a monumental price.

The contrast between Lumumba’s life at Collingwood and the black culture and thought that surrounds him now could not be more stark. Happily distant from the AFL world, he now lives in a city where his name is a byword for moral conviction and strength — indeed, one that boasts a mural of Patrice Lumumba.

Lumumba’s contentment in that exile says much. The United States of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor is no African-American’s idea of utopia.

“I live in South LA,” he says.

“The police have a well-documented history of brutally targeting black and brown people here. I’ve been racially discriminated against in the US in ways that I hadn’t in Australia, and I’m still adjusting to the racism here.

“But the way I see it, the isolation I felt and the prejudice that pervades white Australia is far more detrimental to my wellbeing. To be unable to express oneself naturally is excruciatingly painful.

“At the core of it, what is Australia? Out of respect for First Nations people, I call it ‘So-called Australia’. Its foundations are rooted in the ongoing genocide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the persistent lie of terra nullius.

From that position, Lumumba could easily tune out and switch off. There was a time when he told himself it wasn’t his job to educate people. Then he adopted words of advice from a mentor, the African-American academic Professor Lucius Outlaw Jr:

“The lessons of histories of encounters between white folks and folks African and of African descent have taught us that it is not in our best interests to leave the education of white children and young people solely up to white people. Doing so would not be in the best interests of white folks, either.”

So, Lumumba continues to agitate for change in the AFL, fearing the potential for history to repeat as young African Australians enter new spaces to pursue their dreams. As a child in Perth, Lumumba’s chest swelled when Michael Long took his stand.

“I hope I can inspire children in the same way he inspired me,” Lumumba says.

“He instilled a sense of pride in me and set a powerful example for demanding change.”

That moment has been ongoing. In October, 2014, when Lumumba made his final appearance as a Collingwood player at the club’s Copeland Trophy presentation, much was made of a “bizarre” speech he gave about the true meaning of his name — “the prince, the one who will hold the last laugh, and is gifted”.

Ignored were the far more pointed comments preceding: “We find ourselves in a very interesting time, not only for this football club, but for this whole world. I know that if the Collingwood Football Club is to go to the next level as a football club, it must stand on the right side of history. One thing that I have learned in my journey that I will hold to my heart for the rest of my life is that I know what side of history I stand on.”

How do you end a Heritier Lumumba story?

Perhaps you imagine the years 2030, 2040 and 2050, when 21 old footballers — a little greyer, perhaps a little wider — will dust off their AFL premiership medals and reunite, reminding themselves of the things they did and didn’t do in the name of the Collingwood Football Club.

Side by side they will stand, but will one man be missing?

Lumumba is now less consumed by the bitterness of the world he once inhibited than he is by the richness of the one he returned to. On good days, he wanders down to South Central LA’s own Little Africa with his wife Aja and their son, passing the Patrice Lumumba mural and heading for a square where members of the African diaspora gather in a safe and welcoming space.

Some are drawn there by the unmistakable sound of traditional drums. When Lumumba’s son hears them, he loses his inhibitions and wanders across to join the circle. At first he just nods along, briefly glancing towards his father for approval. Then a small drum is placed before him and his palms connect with its weathered surface, moving in time with those of the elders.

“His name is Yala,” Lumumba says. “It’s a Kikongo word for leadership.”