The speed at which vaccines have been developed has surprised much of the world.

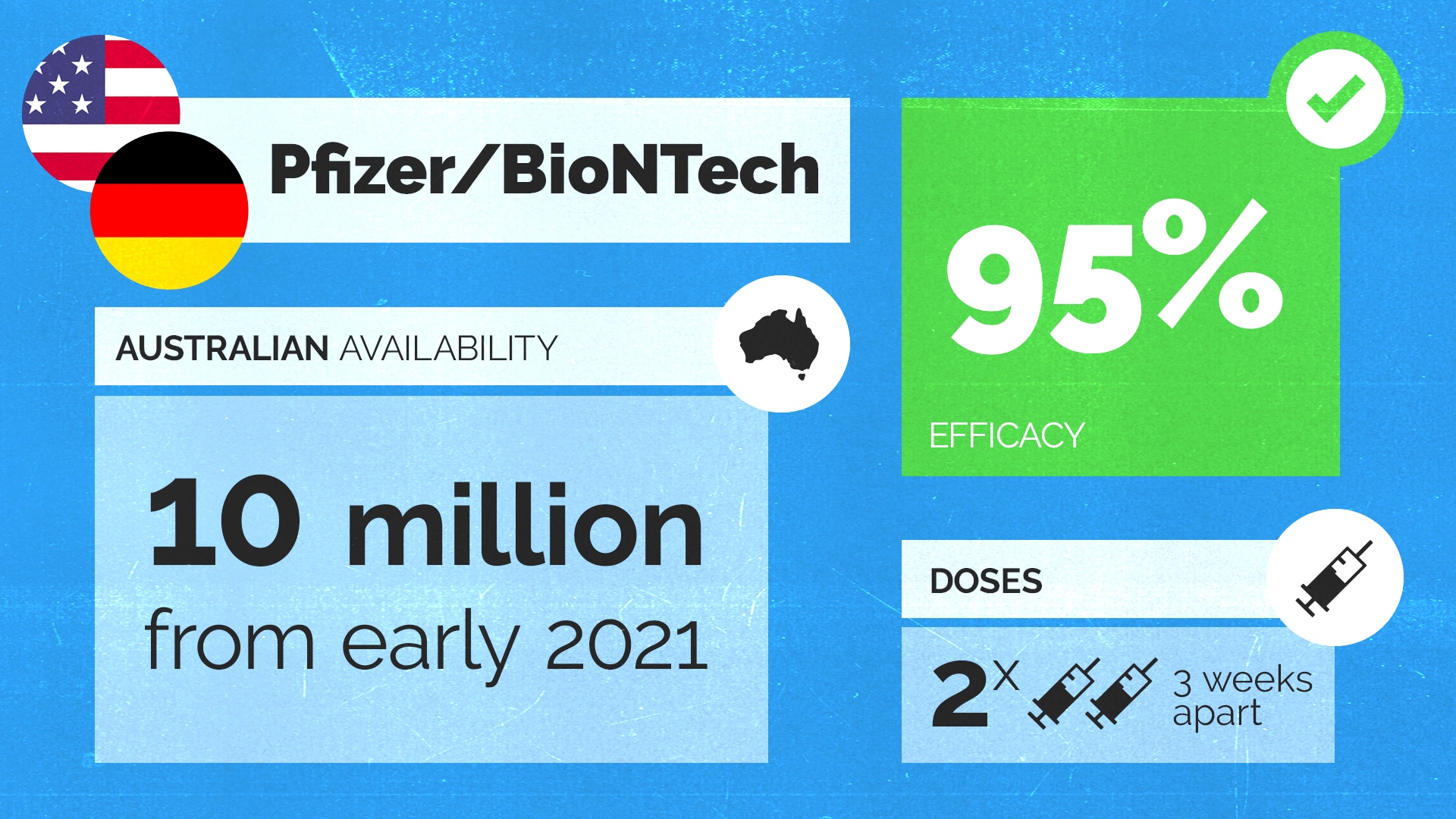

Britain and the United States have granted emergency approval to the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine – and now the Moderna vaccine in the US – with vulnerable communities there already receiving a jab.

And with cases of COVID-19 on the rise again in Australia, it’s left many wondering when the rollout will begin here.

The federal government has reassured the public a vaccine is coming and has begun preparing a comprehensive plan for distribution in the first quarter of 2021, but nothing is set in stone. This is what we know so far.

Why has Australia not approved a vaccine yet?

University of South Australia epidemiologist Professor Adrian Esterman said the answer was simple: there’s no need to hurry.

He said it’s important to remember the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine in the UK and the US has only received “emergency approval”, meaning stage three trials are not finished yet, but the demand is just too great to wait.

“It’s unusual to get this emergency use but because countries like the UK and US are in such dire situations with COVID-19, they couldn’t really wait long enough … and that’s fair enough,” he said.

When will Australia start vaccinating?

“Our regulating authority [the Therapeutic Goods Administration] would much rather wait to get the full trial results, look at them carefully, give them a big tick and then we can start vaccinating,” Professor Esterman said, speaking ahead of the recent outbreak of locally-acquired cases in Sydney.

He expects that will happen for the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine “around March” 2021.

Who will get the vaccine first?

Australia’s acting chief medical officer Paul Kelly has confirmed any vaccines would be rolled out in order of priority groups, with the elderly and those with underlying health issues the first priority.

He said those with increased risk of exposure to the virus, such as health and aged care workers, would be second on the list, followed by those working in emergency services and essential workers.

Which vaccine candidates has Australia invested in?

In light of the decision to abandon the University of Queensland’s vaccine candidate, the Australian government now has three options. All likely require two doses for each person and need to cover a population of 25 million and beyond.

The government made the decision this month to boost its order of Oxford University’s AstraZeneca vaccine from 33.8 million to 53.8 million doses. It is yet to be approved anywhere but results suggest it is up to 90 per cent effective.

“This vaccine is what we call a viral vector. It uses a chimpanzee virus, which is harmless, to infect us and then that delivers the vaccine,” Professor Esterman said.

Australian biotechnology company CSL has committed to making 50 million doses of this option onshore in Melbourne. It has already started the production process but must wait for AstraZeneca to gain regulatory approval before it can be deployed.

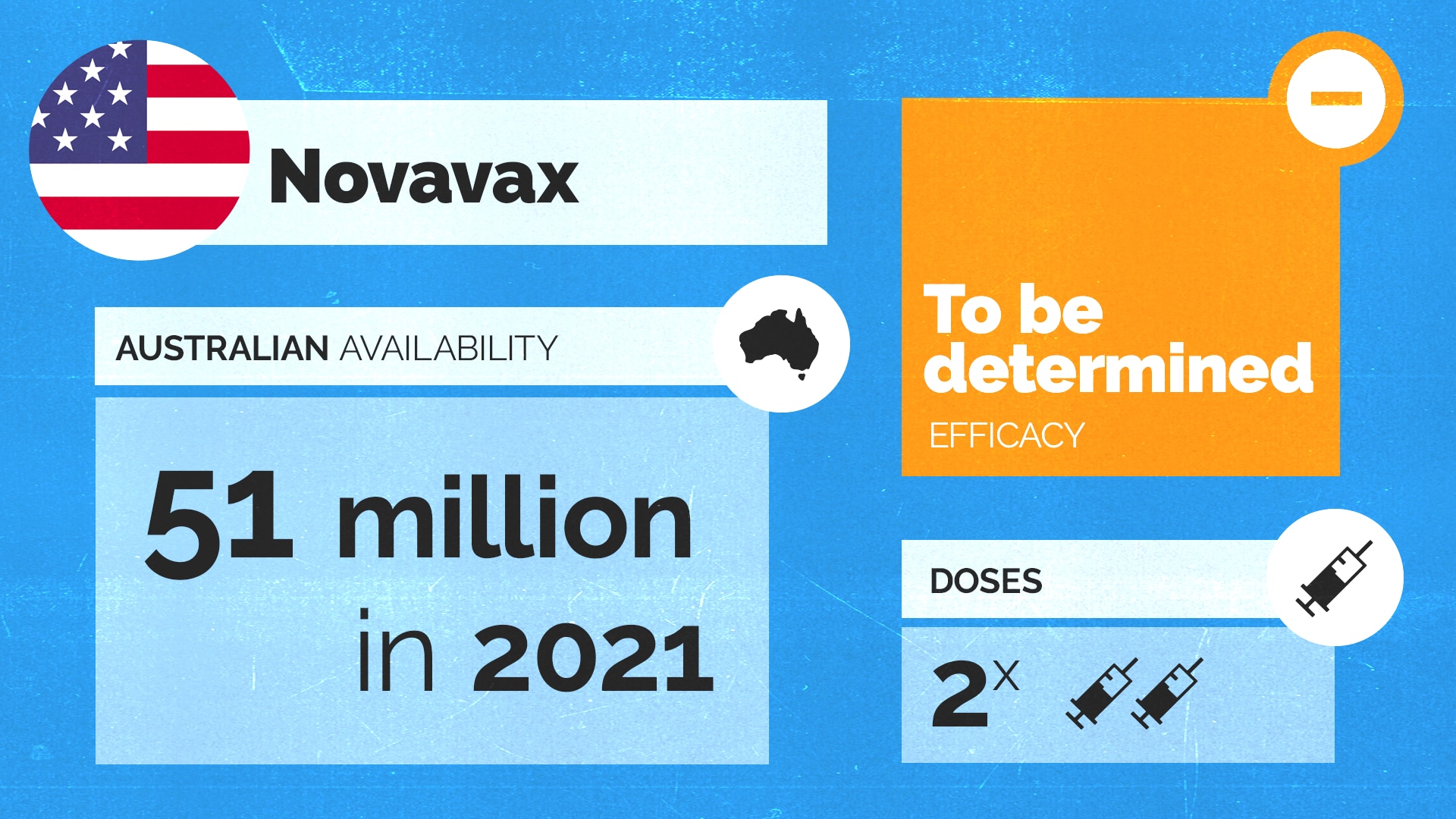

Then there is the option for 51 million doses of the US company Novavax’s vaccine, which is also still in phase three trials.

It’s what Professor Esterman said is called a “protein vaccine”: a tried and tested method that he expects will be approved sometime in the new year.

“They just started phase three trials in September,” he said.

“So again, that really won’t be available probably until at least May or June next year.”

Ten million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine – rated 95 per cent effective – are most likely to reach Australian shores first. The technology for this vaccine, called mRNA, is relatively new and has never been used to develop a vaccine before.

But even if this vaccine is proven effective first, with the need for two doses, only five million Australians will get access to it.

Australian Medical Association vice president Dr Chris Moy said the federal government’s strategy to secure multiple deals was vital.

“Frankly, the issue has been trying to hedge our bets as a nation to be able to access the vaccines which were most likely to succeed,” he said. “It was not possible to have an ‘all eggs in one basket’ strategy.”

But Labor has said having just three potential vaccine deals is not enough and that international best practice is to have five or six.

Isn’t the Pfizer vaccine hard to store?

Yes. It has to be stored at around minus 70 degrees celsius at all times making the rollout of this vaccine slightly more complex.

“It has to be stored in special containers. A bit like eskies, but that hold liquid nitrogen that keeps it extremely cold,” Professor Esterman said.

Asked whether he thinks Australia can handle this extra logistical challenge, he said: “it can be done”.

“Pfizer will be sending it across Australia in these special eskies. Even though it’s more difficult because of that cold chain requirement, it should be quite easily managed in Australia.”

mRNA vaccines like the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine also can’t be produced here in Australia because they involve a new type of technology.

“There’s talk about us developing our own manufacturing ability for the mRNA vaccines and I think that would be a good idea for a future pandemic,” Professor Esterman said.

What happened to the UQ/CSL vaccine?

In a blow to Australia’s bid to develop a vaccine, the University of Queensland and CSL was forced to pull out of the race this month after all trial participants given the dose returned false-positive HIV test results.

“It had no risk of causing infection from HIV,” said Professor Robert Booy, an infectious diseases expert from the University of Sydney.

“What was actually being used was a little bit of protein, nothing to do with the actual infectious virus.”

But scientists were concerned even if the vaccine was completely safe, false-positive results for HIV could interfere with Australia’s HIV testing program, as well as blood donation drives, and public perception and confidence was a concern.

What do Australians think about getting a vaccine?

For any vaccination campaign to be successful, the vast majority of people need to be well-informed and willing.

Melbourne GP Dr Abhishek Verma said after spending the best part of the year quelling his patients’ concerns about COVID-19 he is now dispelling myths about the potential vaccine.

“We’ve had a lot of questions about the vaccinations; is it going to be safe? Is it going to be mandatory? Is it going to be potentially dangerous?” he said.

Fears that corners might have been cut and safety compromised during the race for a vaccine have been playing on many of his patients’ minds.

“What we’re doing is having open dialogues with patients and addressing their concerns,” he said.

“We try to take those opportunities using the data we get from the Department of Health as well as the clinical trials, we try to use evidence-based practice to promote what we believe is a safe and effective vaccination.”

In November, an Australian National University survey of 3,061 Australian adults found 58.5 per cent said they would definitely get a vaccine. Six per cent said they definitely would not.

Will all Australia’s communities be engaged in the rollout?

Dr Verma said for certain new migrant groups, language barriers and a lack of culturally appropriate healthcare options means they’re often left out of the conversation.

“They have traditionally always been somewhat disenfranchised and hard to engage in general practice and primary care,” Dr Verma said. “So I think those people will have specific barriers because they may be more prone to being misinformed if they’re not getting the information from accurate sources.”

State and federal government departments have been criticised during the pandemic for errors in communicating with Australia’s culturally and linguistically diverse communities. From poorly translated information, to a lack of consultation with cultural representatives, it meant some turned to unofficial sources for information about the virus.

Adel Salman, a spokesperson for the Islamic Council of Victoria said “a lot of misinformation [about the vaccine] is happening online” and that battling vaccine misinformation isn’t just a challenge facing Australia’s minority communities, but the entire population.

“I think it’s really important that the right messaging is promoted effectively because there’ll be a lot of fear-mongering, a lot of conspiracy theories spread,” he said. “We need to make sure the messaging can cut through all of that. and we have trusted sources delivering that message in an appropriate way.”

He is calling on the federal government to start an information campaign in advance of the vaccine rollout beginning.

A spokesperson for Health Minister Greg Hunt told SBS News the government will “continue to consult and seek advice and recommendations from the peak multicultural organisations and stakeholders on the COVID-19 response which will include the development and delivery of the vaccine implementation and communication strategy”.

The government has also just established its Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities COVID-19 Health Advisory Group, which met for the first time this month.

What complications could arise?

Professor Paul Griffin, an infectious diseases expert at the University of Queensland, said Australia’s vaccine rollout could be complicated.

“I think the logistics, as well as vaccine hesitancy, are the two main issues we are going to face moving forward. I am not sure we have done enough to address either of those yet,” he said.

“The logistics are going to be incredibly complicated. Basically, we have never done anything like this before.”

“We have a reasonable flu rollout but that involves many different methods of getting that vaccine to people and we still never achieved the rates we would like to see with these COVID vaccines,” he said.

“Also the record-keeping and ability for people to provide evidence of having received a vaccine [are important]. The vaccines we are going to start with at least require two doses, if people don’t come back for their second dose then we might be significantly undermining levels of protection.”

Will the vaccine work?

Dr Moy said there also needs to be more clarity on the short-term versus long-term aims of the vaccination program.

“They are effective in terms of stopping you getting sick but at the moment we are not sure at how good they are at actually stopping you from catching it or even passing it on. So, they may be good at one thing but may not be good at the other,” he said.

“We are not only trying to protect the individual but trying to stop the spread in the community as well. Overall there are pros and cons for all these vaccines and there are a few things that have not been determined yet, such as how long they last.”

When will we know more?

Professor Kelly said the full details about Australia’s vaccination rollout would be made public in January.

People in Australia must stay at least 1.5 metres away from others. Check your jurisdiction’s restrictions on gathering limits. If you are experiencing cold or flu symptoms, stay home and arrange a test by calling your doctor or contact the Coronavirus Health Information Hotline on 1800 020 080.

News and information is available in 63 languages at sbs.com.au/coronavirus

Please check the relevant guidelines for your state or territory: NSW, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Northern Territory, ACT, Tasmania.