news, latest-news, palliative care canberra, clare holland house

By her “nearest and dearest” friend’s bedside, Jackie Stenhouse decided she wanted to help others going through one of the hardest times of their lives. She spent four months caring for her friend as she came to the end of a battle with brain cancer, in Canberra’s Clare Holland House. As she watched volunteers helping patients and family, Ms Stenhouse knew that was exactly what she needed to do. “I noticed there were volunteers in there and would walk around and provide for not only the patients but the families and friends, whether it be making them a cup of tea or holding their hand,” she said. Twelve years later, Ms Stenhouse took the plunge. Every Thursday morning, Ms Stenhouse is part of the team which makes breakfast for patients and visitors, helping to feed those that need assistance and often, just to have a chat. For six months while coronavirus took hold, volunteers weren’t allowed in the facility, and although Ms Stenhouse had since been allowed to return, the role was very different. Visitors were restricted to specific hours outside of her shift, removing the time she used to spend with friends and family. End-of-life care was challenging, but incredibly rewarding for Ms Stenhouse. It could be difficult to keep a distance in the relationships you built, but it was critical in palliative care. “It’s one of the things they teach you,” Ms Stenhouse said. “I find it quite easy to connect with the patients and I think it’s because I spent three months in there with my girlfriend. I had a [man] in there not long ago, whose wife had terminal cancer, she was only 32. I just sat in the tearoom with him and had a chat about everything. “You get a real sense of satisfaction. A lot of the time they just say thank you for listening because they don’t have a lot of people to talk to about it. “I’m just doing my job.” But some patients hit harder than others. When Ms Stenhouse did a short stint in home care, she would take a women’s two children to school every day when she was unable and the two quickly developed a close bond. “One of the things you’re taught in palliative care is not to get close to a patient, which can be really, really hard because she was a similar age to me, she had two young boys and she had a great personality,” Ms Stenhouse said. “Once she went into Clare Holland House I did go and see her on my shift on the Thursday. She was alone and I just sat in there and she held my hand for a good hour. We said absolutely nothing to each then I just got up and said ‘I love you’, and she said ‘I love you’ and that was it. Then she passed away a couple of days later.” Ms Stenhouse said she got as much out of the work as the patients and families. “It makes me feel bloody good. Everyone needs to have support and everyone needs to be cared for with respect and dignity. That’s the main reason I do it,” she said.

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/YSE9Nkng6wVvRADAVf7nRi/0bf282e1-ba84-48b5-a45f-f2f2888614b0.jpg/r1052_811_5568_3363_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

By her “nearest and dearest” friend’s bedside, Jackie Stenhouse decided she wanted to help others going through one of the hardest times of their lives.

She spent four months caring for her friend as she came to the end of a battle with brain cancer, in Canberra’s Clare Holland House.

As she watched volunteers helping patients and family, Ms Stenhouse knew that was exactly what she needed to do.

“I noticed there were volunteers in there and would walk around and provide for not only the patients but the families and friends, whether it be making them a cup of tea or holding their hand,” she said.

Twelve years later, Ms Stenhouse took the plunge.

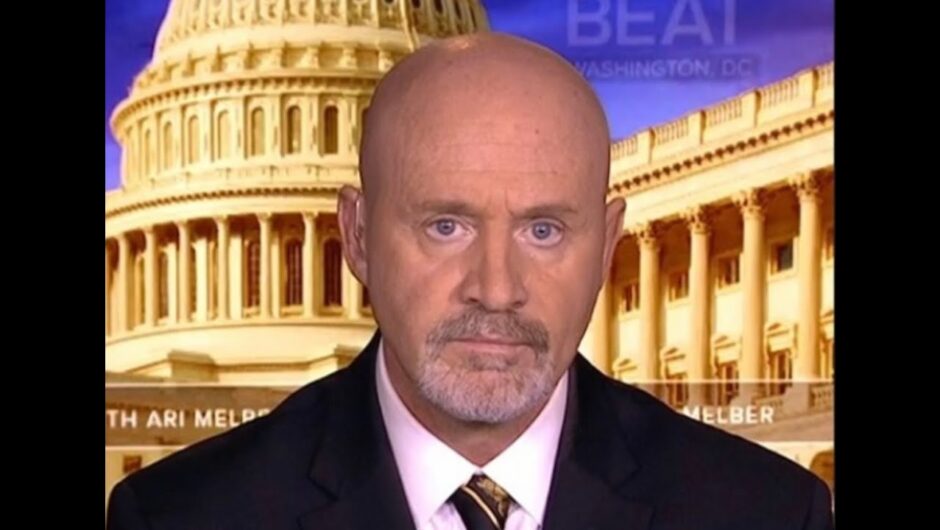

Jackie Stenhouse loves her palliative care work, saying she gets as much out of it as the patients. Picture: Karleen Minney

Every Thursday morning, Ms Stenhouse is part of the team which makes breakfast for patients and visitors, helping to feed those that need assistance and often, just to have a chat.

For six months while coronavirus took hold, volunteers weren’t allowed in the facility, and although Ms Stenhouse had since been allowed to return, the role was very different.

Visitors were restricted to specific hours outside of her shift, removing the time she used to spend with friends and family.

You get a real sense of satisfaction. A lot of the time they just say thank you for listening because they don’t have a lot of people to talk to about it. I’m just doing my job.

Jackie Stenhouse

End-of-life care was challenging, but incredibly rewarding for Ms Stenhouse.

It could be difficult to keep a distance in the relationships you built, but it was critical in palliative care.

“It’s one of the things they teach you,” Ms Stenhouse said.

“I find it quite easy to connect with the patients and I think it’s because I spent three months in there with my girlfriend. I had a [man] in there not long ago, whose wife had terminal cancer, she was only 32. I just sat in the tearoom with him and had a chat about everything.

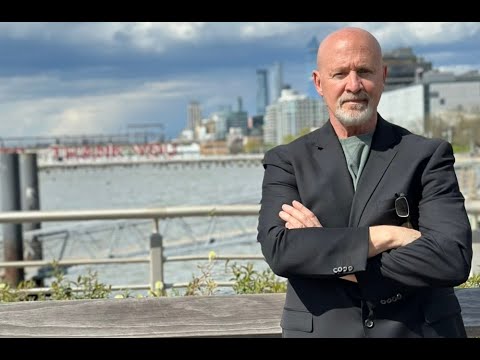

Jackie Stenhouse is one of several volunteers at Clare Holland House who help patients and family, whether it making a coffee or holding their hand. Picture: Karleen Minney.

“You get a real sense of satisfaction. A lot of the time they just say thank you for listening because they don’t have a lot of people to talk to about it.

But some patients hit harder than others.

When Ms Stenhouse did a short stint in home care, she would take a women’s two children to school every day when she was unable and the two quickly developed a close bond.

“One of the things you’re taught in palliative care is not to get close to a patient, which can be really, really hard because she was a similar age to me, she had two young boys and she had a great personality,” Ms Stenhouse said.

“Once she went into Clare Holland House I did go and see her on my shift on the Thursday. She was alone and I just sat in there and she held my hand for a good hour. We said absolutely nothing to each then I just got up and said ‘I love you’, and she said ‘I love you’ and that was it. Then she passed away a couple of days later.”

Ms Stenhouse said she got as much out of the work as the patients and families.

“It makes me feel bloody good. Everyone needs to have support and everyone needs to be cared for with respect and dignity. That’s the main reason I do it,” she said.