After Joe Biden’s victory, these two trends began to merge, as representatives and election officials in several states, having refused the President’s invitation to tamper with the results, faced threats of violence. And so nobody should be even slightly surprised by the fact that, on Thursday morning our time, Trump finally succeeded in encouraging a mob to attempt to violently overturn his election loss.

Sudden, dramatic events are rarely as sudden as they seem. Usually, they come after multiple signs, often explicit warnings, which are dismissed on grounds that seem reasonable enough if taken one by one: this was a harmless joke, that a rhetorical device, that can be explained by the specific circumstances. Yes, details matter. Too often, though, they serve as weak excuses for missing the bigger picture.

Supporters of President Donald Trump climb the West wall of the Capitol building.Credit:AP

Australia is a very, very long way from what is happening in America. But there are three concerning elements of the Australian political landscape that are too often given only mild attention, ignored entirely, or dismissed as sideshows.

The first is the overtone of racism in much of our public debate. For years, Pauline Hanson was given prime television spots on both Channel Nine, which owns this masthead, and Channel Seven. Alan Jones was officially found to have incited violence in the lead-up to the racist Cronulla riots, perhaps the most prominent act of political violence in our history – and he is a powerful broadcaster still, feted by politicians. In 2020, people with dark skin who broke COVID-19 rules were named and shamed in the national media, while white people from rich suburbs had their identities protected.

The promotion of racism is one problem. The failure to cover the damaging effects of racism is another. In 2019, a terrorist massacred 51 people – all Muslims – in New Zealand. He was Australian, and actively engaged online with Australian far-right groups. Somehow, though, we have largely managed to ignore the possibility that he might have drawn, to some extent, on the discussions of these topics in the country of his birth.

Second, there is the increasingly concerning social media reach of Sky News. Its TV viewership is tiny. But, as journalist Cameron Wilson recently reported, their YouTube videos have been seen 500 million times, “more than any other Australian media organisation. Facebook posts from their page had more total interactions last month than the ABC News, SBS News, 7News Australia, 9 News and 10 News first pages”. And these posts are seen overseas, not just in Australia. What are they broadcasting? Often enough, far-right talking points, among them a number of conspiracy theories.

New Zealand crowds outisde court mobilise in support of the victims of an Australian terrorist.Credit:Getty Images

Finally, there is our own Prime Minister’s contemptuous attitude towards the conventions of our democracy. In 2017, Morrison named Donald Trump as a political model, along with British Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. Both, he said, had taken “on the role of the authentic outsider; challenging a system that many voters did not think was serving them any longer”. Sure enough, once he became Prime Minister, Morrison began positioning himself in opposition to that system. In the space of weeks he attacked government at a federal level (his party was a “muppet show”), state level (COAG was a waste of time), and international level (climate meetings were “nonsense”).

These were only words; but his actions suggest similar. He has a cavalier approach to Parliament, several times having misled the House – which, before he came to power, was regarded as a very serious offence, even a sackable one. He has twice misled the House to defend his ministers, and been forced to correct the record. Most concerningly, he misled the House when answering questions about sports rorts – a scandal which itself raised concerns about his attitude towards accountability. And after those rorts came to light, the body which discovered them – the Audit Office – had its funding cut.

Loading

What matters is not just these individual events – some of them may, on their own, seem small. The story of the past few years in America, and increasingly here, is their overlap, the way that they collide in dangerous ways and fuel each other. Bit by bit, our politics is becoming vulnerable to a loose, and often unintentional, alliance of fantasists, racists, and politicians willing to disregard convention. In other words, a gradual accumulation of exactly the same factors that bled into this week’s violence in America.

It’s worth briefly mentioning a few of these combinations. The Coalition MP George Christensen has amplified Trump’s conspiracy theories about the US election. On Thursday, one journalist asked Morrison if he would condemn this – the Prime Minister responded, “Australia’s a free country”. This is understandable, because Morrison himself, during the bushfires, was happy to wink at false conspiracy theories rather than talk about climate change.

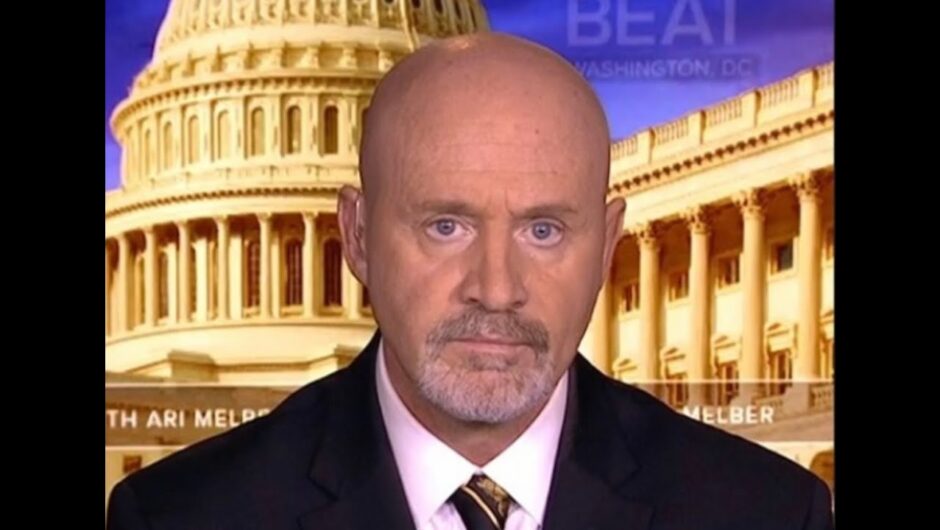

Scott Morrison isn’t Donald Trump but some of the elements that brought Trump to power in the US are evident here.Credit:AP

Then there is the regular appearance of the Canadian far-right figure Lauren Southern on Sky TV. As journalist Jason Wilson has pointed out, Southern is fond of the “Great Replacement Theory” beloved of neo-Nazis, which holds that white people are slowly being replaced by non-whites. So is Brenton Tarrant, the Christchurch massacrist. And one of our former prime ministers, Tony Abbott, has praised the Hungarian Prime Minister, a great fan of the theory, while seeming to echo some of its rhetoric.

Loading

On Thursday, the headline across The New York Times website read, “MOB INCITED BY TRUMP STORMS CAPITOL”. It was the type of headline you might not have seen a few years ago, and not just because of the absence of such craziness – the Times would have been more shy about connecting the President so directly to what had happened, however clear the facts.

That was because the assumption of the media was that both sides of any issue had to be reported. In politics, that meant reporting what both sides said as though each had a reasonable claim on truth, and steering clear of outright condemnation. This works fine, until one side abandons any relationship to the truth, or to decency. Donald Trump abandoned both. Gradually, the media realised that the only way it could stay faithful to the facts was to report what was actually happening – Trump was lying, and endangering democracy – rather than a bland and balanced account of what Trump said and what his opponents said.

Donald Trump posed a dilemma for the traditional media.Credit:Alex Brandon

One result, it seems, is that some people – encouraged by Trump – simply turned away from mainstream media, and towards social media channels, with the same result: they were not getting the facts. What, then, is the solution?

The sad truth is that by the time a figure like Trump is elected, there may not be a solution. The Times made the right adjustments; but made them too late.

Which brings us back to Australia.

Loading

American exceptionalism may be dying a slow death. Australian exceptionalism, on the other hand, seems at an all-time high. We came through the financial crisis; we came through COVID. How good is Australia? But Australia is prone to the same dangers as any other country. Our island status might offer some protection from a virus; it cannot protect us from hatred, fantasy, or inflammatory rhetoric.

Sure, Scott Morrison isn’t Donald Trump – nor will he morph into Donald Trump. And Australia is not America. But that is no great boast – it merely means we still have time, if we don’t want a Trump-like figure to emerge here.

What the American media learned, too late, was that they had to adjust their conventions to a new era. It is past time for our media to begin a similar adjustment. For some, it will mean rethinking the guests they invite on air. Most will have to change the way they respond to racial issues. More attention will have to be given to the interactions between social media, racism, and politics. It will mean accurately describing not what politicians say they are doing, but what they are actually doing – with particular attention given to actions that undermine our democratic institutions.

One of our advantages over those who don’t care much for democracy is that they tend to give us fair warning – just like Donald Trump did. They say what they intend to do, and then they do it. Their great advantage is that the rest of us, including the media, tend to ignore those warnings in the blind hope we can just carry on as though nothing at all has changed.

US power and politics

Understand the election result and its aftermath with expert analysis from US correspondent Matthew Knott. Sign up here.

Sean Kelly is a columnist for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald and a former adviser to Labor prime ministers Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard

Most Viewed in National

Loading