Lovemore Ndou was 16 when a cashier flirted with him at the supermarket.

It might seem innocuous, but a white woman flirting with a black man in South Africa during apartheid was anything but.

When authorities weren’t able to pin a sexual assault on him, they instead accused him of theft before taking him to a cell where they broke his arm and let a dog — trained to “kill black people on sight” — almost tear out his eye.

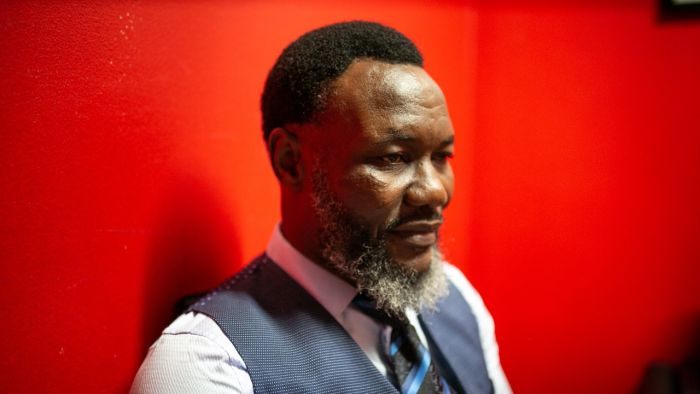

It’s left a scar he still bares next to his eye socket — a reminder of the three-time world welterweight champion’s childhood in a country where race defined lives.

“It made me realise a black man’s life in South Africa was worthless at the time,” Mr Ndou said.

“My own life was nothing in my country. I decided in the hospital bed I’d be a lawyer one day.”

Mr Ndou, 49, practices family and criminal law from an office at Rockdale, in Sydney’s south.

In his new book, Tough Love, he reveals he did not receive a formal education until he was nine years old and when he first went to TAFE in Sydney he had to ask his stepdaughter to teach him how to use a computer.

Since coming to Australia in 1996, he’s earned six degrees across law, human rights and political science.

But Mr Ndou has always been a self-styled “poster boy for the underdog” in and out of the ring.

He grew up in a town called Musina, a border town between South Africa and Zimbabwe.

With apartheid’s dehumanisation on one side and a civil war raging on the other, he witnessed humanity at its darkest.

Aged eight, he witnessed rapes and murders in his community at the hand of guerilla fighters loyal to Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe.

Five years later, his best friend died in his arms after being shot by a white police officer during an apartheid protest.

A rage brewed inside Mr Ndou — and while he was a keen sportsman, his fiery temper saw him thrown out of most matches.

One day, a security guard escorting him off a football field after yet another outburst suggested he try boxing.

This man, Divas Chirwa, would become his trainer and help launch his career into the World Boxing Council (WBC) ranks.

“I was wrong that you needed to be angry to fight, boxing is scientific,” he said.

“It’s like playing a game of chess you need to be thinking, and it’s only when you’re calm that you think straight.

“That lesson changed me as a boxer, it changed me as a person.”

But no matter how formidable he was in the ring, he couldn’t escape the racial discrimination.

Although South Africa lifted a ban on interracial fights in 1973, the bouts were rarely evenly judged.

Mr Ndou had to take it to the extreme to secure a win — many of his opponents would leave the ring with a broken nose if they weren’t knocked out.

It was a dirty play and Mr Ndou knew if he stayed, his career would become compromised.

“I’d done my research and knew this country had a keep Australia white policy so I didn’t expect the treatment to be different,” he said.

“But when I arrived, they treated me like a human being.

“I got a shock when I saw a white person cleaning my toilet in the hotel.”

Because of his experience, Mr Ndou doesn’t believe Australia is a racist country even if he believed there was racial injustice.

“We can’t judge the whole country on those incidents, perhaps I think that way because I come from somewhere where racism was legislated,” he said.

However, he says the black lives matter movement holds reckoning for the nation.

“‘When we say black lives matter, we’re not saying other lives don’t matter but in the context of people dying in custody, it’s black people,” he said.

“We need focus.”

Mr Ndou’s most memorable win came in 2010, when he won his second world title in South Africa.

“To go back to that country that I had to leave years ago because I wasn’t given the opportunities that I needed as a fighter, to fight in front of my people and win the world title, it was amazing,” he said.

When the judges declared he had won by unanimous decision, he dedicated the victory to Nelson Mandela.

Mr Ndou is about to earn his seventh degree in law, communication and politics, and devotes part of his week to doing pro bono work for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients.

He doesn’t trade blows as much as he used to but is considering entering a different kind of fray.

“I’ve been vocal about entering politics and taking on corruption will be my next step,” he said.

He doesn’t expect to keep the gloves on if he makes it into the political arena.

“I’m a tough person, I’ll push through,” he said.