news, latest-news, namadgi national park, helicopter, fire, georgeina whelan, orroral valley

Just after midday on January 27, 2020, Georgeina Whelan went to the supermarket. The Emergency Services Agency commissioner had found a rare quiet moment in a month which had seen a blaze erupt near Canberra Airport and a freak hailstorm lash the city, all while fires from the Snowy Mountains continued to march toward the ACT’s western fringe. Whelan took the chance to stock up the family fridge with food for her husband and children. The first-year commissioner said she was in the supermarket when she took the call. A fire had ignited in the heart of Namadgi National Park, she was told. A quiet day no longer. The blaze sparked in the Orroral Valley would develop into the ACT’s biggest fire emergency since 2003, eventually scorching 80 per cent of Namadgi’s rugged landscape. No homes or lives were lost in the territory, but 12 properties were destroyed after the fire skipped the border into NSW. The ACT’s response was praised by many, but not all. Many of the harshest critics were those involved in – or with inside knowledge of – the operation, including ACT Rural Fire Service staff, volunteers and members of the government’s own expert bushfire council. Scrutiny of the Australian Defence Force’s part in the events of January 27 has increased as more information has been brought to light. But 12 months on, questions still linger. Could this environmental catastrophe have been avoided? Could the damage have been limited? The circumstances surrounding the fire’s ignition remain the subject of intrigue and contention. Did the Defence MRH-90 Taipan helicopter which accidentally sparked the blaze need to be flying in Namadgi on that day, one of severe bushfire danger? And did the 45-minute delay in the helicopter crew reporting the fire’s exact location prevent or hinder its containment? The Emergency Services Agency, which sent the helicopter into the national park on January 27 to find locations suitable for dropping off and collecting remote firefighting crews, has publicly insisted Defence performed a “critical” role in its bushfire preparations. But as reported by The Canberra Times, at least one senior figure inside the ACT’s response questioned if the helicopter was there out of necessity, or simply for publicity. Others veterans of Canberra fires have privately observed that if the ESA wanted to know where to land helicopters in Namadgi it need only have asked Parks and Conservation or the two local RFS brigades, who know the vast national park like the back of their hand. Once the helicopter’s landing light had sparked the fire at about 1.30pm, the blaze quickly spread amid hot and dry conditions. By 8pm the next day the fire had burnt through more than 8100 hectares. Revelations that the helicopter crew only alerted ACT authorities to the exact location of the blaze after they completed an emergency landing at Canberra Airport at 2.15pm raised the immediate question of whether an earlier message could have hastened the response. Defence has stood by the response, saying the pilot’s priority at the time was to return the crew to safety after the helicopter was damaged in the fire. Whelan, speaking to The Canberra Times in an interview to mark 12 months since the fire’s ignition, doesn’t think it made a difference. The commissioner said ACT fire crews had already been deployed to Namadgi before the Defence helicopter landed at Canberra Airport, after smoke was spotted from the Mt Tennent lookout tower at around 1.49pm (19 minutes after the fire’s ignition). Whelan accepts that her crews didn’t know the exact location of the fire when they left for Namadgi. But she points out that the crews would have taken the same roads as they did even if they had known precisely where they were headed. “Have I gone through line-by-line to analyse the difference between 12 minutes, 19 minutes and 45 minutes [response time]? No I haven’t,” she said. “What I have focused on, and what I’m comfortable with, is that the response that we provided was a very appropriate one. “It was very unlikely that we would have been able to contain that fire.” Amid ongoing public anger over the 45-minute reporting delay, Whelan has repeatedly refused to criticise the helicopter crew’s actions. There has been suspicion, including among volunteer firefighters, that Whelan’s previous career in the Australian Defence Force has made her reluctant to speak out. “Absolutely not,” Whelan said when The Canberra Times put the suggestion to her. “If you were to talk to any of my ADF colleagues … they will tell you that I did myself no favours with how direct and open I was if I thought something was wrong. “My commitment is to the ACT community and to the men and women that I am responsible for every day, and I say that very genuinely.” Whelan said her military experience meant she understood that a pilot’s priority in an emergency was the safety of their crew. She pointed out that on January 23 – four days before the Orroral Valley fire ignited – an air tanker had crashed in the Snowy Mountains region, killing three passengers. By January 31, 2020, the Orroral Valley fire had burnt to within a few kilometres of Canberra’s southern outskirts, with fire projection maps showing that Tharwa, Banks, Gordon and Conder could come under ember attack in the following days. Whelan said predictions about the worst-case scenario were informed by a combination of traditional fire spread modelling and assumptions based on the “unprecedented” bushfire behaviour witnessed in other parts of Australia through the Black Summer. “We could see and were listening to colleagues nationally using the term ‘this is unprecedented’ and ‘we have never seen fire behave in this manner in our career lifetime’,” she said. New Rural Fire Service chief officer Rohan Scott, who was filling the incident controller position inside ESA headquarters when the Orroral Valley fire ignited on January 27, said the ACT was far more prepared than in 2003 to combat a major emergency. “From a capability perspective, if we were to be impacted, we had learnt a lot from ’03,” he said. “We had better evacuation, better messaging for the public, better resilience in the community, asset protection zones … we get better fire modelling.” The fire was at its most threatening on Saturday, February 1, before conditions eased in the late afternoon. The fire continued to burn for more than three weeks but never again posed a risk to the ACT. While Whelan’s team was widely praised for its handling of the emergency, the tactics deployed – particular the use of air tankers in the hours after the fire’s ignition – have been called into question. In evidence to the ACT Legislative Assembly’s inquiry into the fire season, senior volunteer firefighter Garry Mayo said crews had to be pulled off the fireground as they waited for the tanker to drop retardant, potentially costing them valuable time which could have been spent trying to contain the emerging blaze. In the weeks and months after the fire was extinguished, The Canberra Times reportedly extensively on the angst and frustration of volunteers and paid staff about the handling of the fire season. At one point over the summer, a group of volunteers felt so mistreated that they considered walking off the fireground in disgust. Whelan now acknowledges that “some of the communication was not as good as it could have been”, though she doesn’t believe it had any material impact on the fireground. She said, and Scott agrees, that volunteers want to be looped into the agency’s thinking during multi-day “campaign” fires. They want to be told why they are being deployed to certain locations. The commissioner was also confident that concerns some paid RFS staff members expressed in a damning post-season review had been resolved. Feedback to the review included claims of a “blame and shame” culture inside ESA headquarters, serious allegations about Whelan’s behavior and pointed criticism of aerial firefighting tactics. “I may not necessarily have agreed [with what they said], nor may have my chief officers or even their colleagues,” Whelan said. “[But] we created an environment where we allowed people to share their experience. “We have worked through the issues and if you were to talk to a number of staff who had very, very firm views about how the operations were conducted, what you would see is that they would feel comfortable and confident that they have been heard and we are really responding.”

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/znhWFHRUTrpRC32tGqnZkk/1bbf5f08-2146-40e0-93aa-da8abd8cd743.jpg/r3_373_5998_3760_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

Just after midday on January 27, 2020, Georgeina Whelan went to the supermarket.

The Emergency Services Agency commissioner had found a rare quiet moment in a month which had seen a blaze erupt near Canberra Airport and a freak hailstorm lash the city, all while fires from the Snowy Mountains continued to march toward the ACT’s western fringe.

Whelan took the chance to stock up the family fridge with food for her husband and children.

The first-year commissioner said she was in the supermarket when she took the call.

A fire had ignited in the heart of Namadgi National Park, she was told. A quiet day no longer.

The ACT’s response was praised by many, but not all. Many of the harshest critics were those involved in – or with inside knowledge of – the operation, including ACT Rural Fire Service staff, volunteers and members of the government’s own expert bushfire council.

Scrutiny of the Australian Defence Force’s part in the events of January 27 has increased as more information has been brought to light.

But 12 months on, questions still linger.

Could this environmental catastrophe have been avoided? Could the damage have been limited?

The circumstances surrounding the fire’s ignition remain the subject of intrigue and contention.

The Orroral Valley fire, moments after it was sparked on January 27. Picture: Department of Defence

The Emergency Services Agency, which sent the helicopter into the national park on January 27 to find locations suitable for dropping off and collecting remote firefighting crews, has publicly insisted Defence performed a “critical” role in its bushfire preparations.

But as reported by The Canberra Times, at least one senior figure inside the ACT’s response questioned if the helicopter was there out of necessity, or simply for publicity.

Others veterans of Canberra fires have privately observed that if the ESA wanted to know where to land helicopters in Namadgi it need only have asked Parks and Conservation or the two local RFS brigades, who know the vast national park like the back of their hand.

Once the helicopter’s landing light had sparked the fire at about 1.30pm, the blaze quickly spread amid hot and dry conditions. By 8pm the next day the fire had burnt through more than 8100 hectares.

Defence has stood by the response, saying the pilot’s priority at the time was to return the crew to safety after the helicopter was damaged in the fire.

Whelan, speaking to The Canberra Times in an interview to mark 12 months since the fire’s ignition, doesn’t think it made a difference.

The fire burnt through 80 per cent of Namadgi National Park. Picture: Karleen Minney

The commissioner said ACT fire crews had already been deployed to Namadgi before the Defence helicopter landed at Canberra Airport, after smoke was spotted from the Mt Tennent lookout tower at around 1.49pm (19 minutes after the fire’s ignition).

Whelan accepts that her crews didn’t know the exact location of the fire when they left for Namadgi. But she points out that the crews would have taken the same roads as they did even if they had known precisely where they were headed.

“Have I gone through line-by-line to analyse the difference between 12 minutes, 19 minutes and 45 minutes [response time]? No I haven’t,” she said.

“What I have focused on, and what I’m comfortable with, is that the response that we provided was a very appropriate one.

“It was very unlikely that we would have been able to contain that fire.”

Questions of ADF conflict

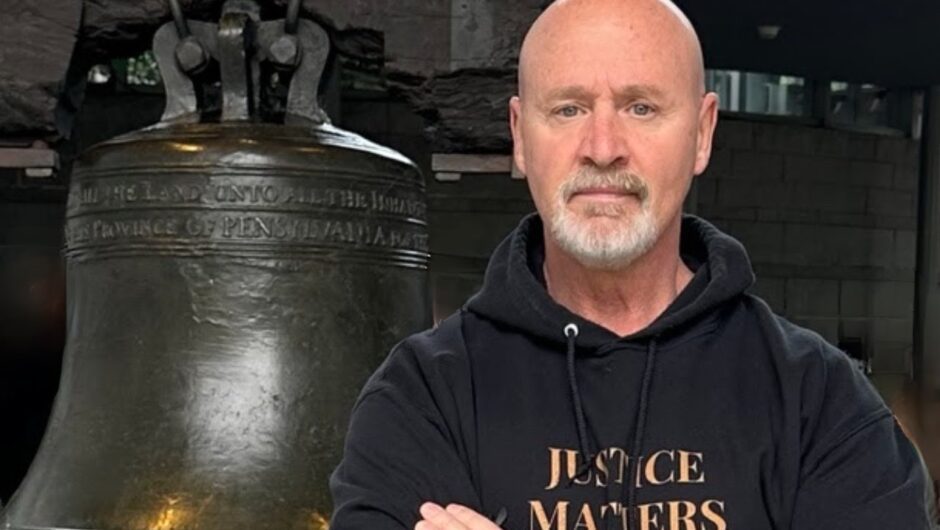

Whelan and ACT Parks manager Brett McNamara disembark from an MRH-90 Taipan helicopter at Mt Ginini. Picture: Department of Defence

Amid ongoing public anger over the 45-minute reporting delay, Whelan has repeatedly refused to criticise the helicopter crew’s actions.

There has been suspicion, including among volunteer firefighters, that Whelan’s previous career in the Australian Defence Force has made her reluctant to speak out.

“Absolutely not,” Whelan said when The Canberra Times put the suggestion to her.

“If you were to talk to any of my ADF colleagues … they will tell you that I did myself no favours with how direct and open I was if I thought something was wrong.

“My commitment is to the ACT community and to the men and women that I am responsible for every day, and I say that very genuinely.”

‘We learnt a lot from 2003’

By January 31, 2020, the Orroral Valley fire had burnt to within a few kilometres of Canberra’s southern outskirts, with fire projection maps showing that Tharwa, Banks, Gordon and Conder could come under ember attack in the following days.

ACT Rural Fire Service chief officer Rohan Scott. Picture: Karleen Minney

Whelan said predictions about the worst-case scenario were informed by a combination of traditional fire spread modelling and assumptions based on the “unprecedented” bushfire behaviour witnessed in other parts of Australia through the Black Summer.

“We could see and were listening to colleagues nationally using the term ‘this is unprecedented’ and ‘we have never seen fire behave in this manner in our career lifetime’,” she said.

New Rural Fire Service chief officer Rohan Scott, who was filling the incident controller position inside ESA headquarters when the Orroral Valley fire ignited on January 27, said the ACT was far more prepared than in 2003 to combat a major emergency.

“From a capability perspective, if we were to be impacted, we had learnt a lot from ’03,” he said. “We had better evacuation, better messaging for the public, better resilience in the community, asset protection zones … we get better fire modelling.”

The fire was at its most threatening on Saturday, February 1, before conditions eased in the late afternoon. The fire continued to burn for more than three weeks but never again posed a risk to the ACT.

While Whelan’s team was widely praised for its handling of the emergency, the tactics deployed – particular the use of air tankers in the hours after the fire’s ignition – have been called into question.

‘Our communication was not as good as it could have been’

Whelan says lessons have been learnt from the 2019-20 fire season, the ACT’s worst since 2003. Picture: Dion Georgopoulos

In the weeks and months after the fire was extinguished, The Canberra Times reportedly extensively on the angst and frustration of volunteers and paid staff about the handling of the fire season.

Whelan now acknowledges that “some of the communication was not as good as it could have been”, though she doesn’t believe it had any material impact on the fireground.

She said, and Scott agrees, that volunteers want to be looped into the agency’s thinking during multi-day “campaign” fires. They want to be told why they are being deployed to certain locations.

The commissioner was also confident that concerns some paid RFS staff members expressed in a damning post-season review had been resolved.

“I may not necessarily have agreed [with what they said], nor may have my chief officers or even their colleagues,” Whelan said.

“[But] we created an environment where we allowed people to share their experience.

“We have worked through the issues and if you were to talk to a number of staff who had very, very firm views about how the operations were conducted, what you would see is that they would feel comfortable and confident that they have been heard and we are really responding.”