In this extract from Sandra Hogan’s new book With My Little Eye, a pair of Russian defectors find themselves living with a family of ASIO spies.

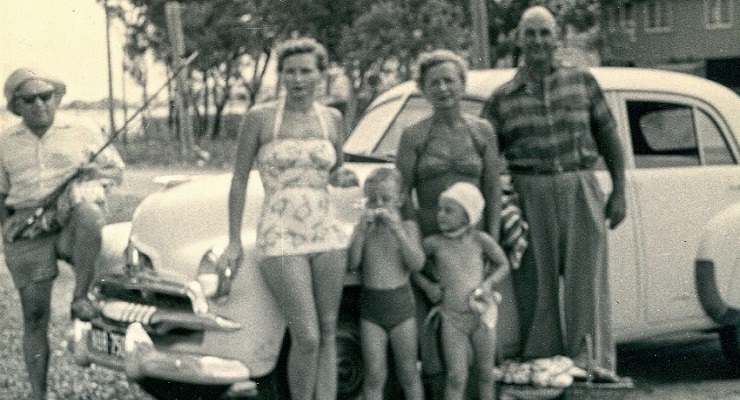

Evdokia Petrov, Sue-Ellen Doherty and an unidentified ASIO office (Image: Supplied)

Dudley and Joan Doherty and their children, Amanda, Sue-Ellen and Mark lived an ordinary suburban existence in 1950s Brisbane. Ordinary, except the Dohertys both worked for ASIO and their children were in on the secret. In this edited extract from With My Little Eye, author Sandra Hogan recounts the time Australia’s most famous Russian defectors, the Petrovs, came to stay.

Joan was on her knees beside the tub, bathing Sue-Ellen and Mark, when she met Russian defector Evdokia Petrov. Dudley ushered Mrs Petrov into the room and, while the children squealed and splashed, the two women made stilted conversation. Mrs Petrov had come to look Joan over and decide whether she and her husband Vladimir would come to live with the Doherty family for two months.

It was November 1956, and

the Olympic Games were about to be held in Melbourne. There was enormous

excitement in sport-mad Australia: it was the first time an Olympic Games had

been held outside Europe.

But the Olympics are never just about sport. Joan and Dudley, inveterate news followers, had been closely following the political lead-up to the “friendly games”, in which sporting venues turned into battlefields, with the Soviet Union and the USA fighting for supremacy. The Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland withdrew from the Games in protest at the Soviet Union’s presence. A total of 46 athletes defected from the East to the West during the Games.

Colonel Vladimir Petrov and his wife, Captain Evdokia Petrov, had arrived in Australia in 1951. He was the third secretary at the Soviet Embassy in Canberra and she was a code clerk, but their real role was intelligence; they were notable for having survived a series of bloodthirsty purges during the 20 years of their intelligence careers in Moscow.

One of Petrov’s roles in Australia was to recruit people to penetrate the organisations of anti-Soviet Russians and Balts. He met, and cultivated, the young Polish doctor, Michael Bialoguski, who had many patients from the Soviet Union and was open about his pro-Soviet views. Petrov gave him the code name Grigorii.

What he didn’t realise was that Bialoguski was already working as an undercover agent for ASIO. The two became constant companions, drinking together at the California Cafe and Abe Saffron’s Roosevelt Club during Petrov’s regular visits to Sydney, and cruising Kings Cross in the early mornings looking for women.

Bialoguski suggested to

ASIO that Petrov might be a candidate for defection and, with ASIO’s

permission, he courted Petrov: first with hints about the pleasures of life in

Australia, and finally with a direct offer to buy the Petrovs a chicken farm

outside Sydney with the unlikely name of Dream Acres.

Moscow’s MVD (the Soviet

Ministry of Internal Affairs) realised fairly quickly that Petrov was not

producing results from his intelligence work and was drawing negative attention

to the Soviet Embassy with a series of drunken incidents, including one in

which he nearly ran over a police constable.

In January 1954, Petrov

was threatened with recall to Moscow and he knew enough about Moscow politics

to believe he would be executed on his return. He shared his feelings with

Bialoguski and, shortly afterwards, ASIO briefed Prime Minister Menzies on the

possibility of a defection.

On 3 April 1954, ASIO agent Ron Richards drove Vladimir Petrov to a safe house on Sydney’s north shore and handed him a parcel containing £5000. In exchange, Petrov passed Richards the documents in his satchel. Petrov had now defected — but his wife didn’t know yet.

When the Soviets discovered that Petrov had defected, they imprisoned Evdokia in a single room of the embassy and booked her on a flight from Sydney to Moscow on April 19.

The time of the flight was publicised, and a crowd of intensely emotional people — mostly refugees from the Soviet Union — came to witness Evdokia’s departure. The crowd watched her apparently being frogmarched to the plane by two grim Soviet apparatchiks. They called out to her, believing she was being dragged to her death. They saw her lose a shoe as they pushed towards the plane and heard her cry out in fear.

The dramatic photos in the paper next day prompted urgent national action. Prime Minister Menzies instructed ASIO head Charles Spry to approach Evdokia at the airport in Darwin and ask if she wanted to seek asylum in Australia. She agreed to put herself under the protection of the Australian government.

These events had occurred

two years before Evdokia appeared in Joan’s bathroom. The Petrovs were by then

living in Melbourne and, as the Olympics drew closer, they were desperately

afraid. Nobody knew better than they did how easy it would be for Russian intelligence

officers to come to Australia with the Olympic team, posing as coaches or

physiotherapists: it would take only one of them to assassinate the Petrovs.

ASIO decided to move the Petrovs out of Melbourne to safety for two months.

Petrov followers called it “the lost two months”. Nobody knew what happened to the Petrovs during that time until ASIO historians tracked down Joan in Brisbane in 2011 and briefly recorded that they had been staying with the Doherty family. No other details of those two months have been recorded until now.

ASIO’s personnel officer, who Joan remembers was called “Mac”, suggested that a young family in Queensland would be a good cover for the Russian defectors. They would look like a family group, with grandparents. Dudley agreed; the next step was for Evdokia to inspect the Doherty household and decide whether it was acceptable to her.

The meeting of the two women — the Russian spy and the Australian spy — in a cramped Brisbane bathroom was not a great social success. But Evdokia agreed to go and live with the Dohertys.

ASIO arranged for them all to stay in a two-storey house in the centre of the booming holiday town of Surfers Paradise south of Brisbane. The Petrovs lived upstairs and the Dohertys lived downstairs — the usual living arrangement for ASIO agents sheltering people. The only instructions ASIO gave the Dohertys were “keep ’em out of trouble” and “watch Jack”. Jack was the cover name for Vladimir Petrov, and they soon found out why they had to watch him. Jack was often drunk, bad-tempered and unreliable.

“He was a peasant from Siberia,” said Joan, dismissively. She was talking to Sue-Ellen, years later, when Sue-Ellen was on her quest to find out more about her childhood. “None of us liked him. He was strange, very crude.”

Evdokia was different. After a stiff beginning, Joan and Evdokia quickly became great friends — as much as it’s possible for an ASIO spy and a reluctant Soviet defector to be friends. The Dohertys called Evdokia “Peewee”, for reasons that no one can remember now, and they found her to be an intelligent and caring person.

Peewee was 15 years older than 26-year-old Joan, but they were both attractive women. Peewee liked to flirt with men and to talk about clothes. Neither woman had much money for dresses, but they loved to window-shop together in the new boutiques that were opening up in Surfers. Peewee was always beautifully dressed, unlike her husband, who wore a uniform of grubby old khaki shorts and socks with sandals.

Their days quickly fell into what looked like a comfortable holiday pattern. Dudley would take Jack and five-year-old Mark out to the river to fish. “Good. He’s gone,” Peewee would say to Joan, glad to be rid of her husband. “We can enjoy ourselves.” Joan and Peewee would take Sue-Ellen to the pub on the corner of Cavill Avenue and sit in the beer garden. Sue-Ellen would play on the swings, and Joan and Peewee would sip their drinks and watch the young people.

“We both liked watching people,” said Joan. “We had a lot in common.” Indeed they had, as both were trained watchers. But they did not talk shop. Not ever. They were just two pretty women having a drink.

The unspoken rule was

that the Dohertys would not visit the Petrovs upstairs without an invitation,

as that would be an invasion of privacy, but the Petrovs could always visit the

Dohertys. Sue-Ellen would have ignored the rule and followed Peewee upstairs if

she were allowed, but Joan forbade it and Peewee would shoo her out. Sue-Ellen

would cry but Joan was firm.

There was more than protocol at stake: Joan was determined not to let Sue-Ellen see what she herself had seen upstairs. “Petrov would sit on a big rattan chair and he’d take his trousers off and just sit there all exposed,” said Joan. “You’d say now he was a dirty old man.”

Joan’s tone as she said this was objective, non-committal, but that was her professional spy voice. The nightmares she endured then were not about Russian assassins but about the presence of grubby Petrov in her home, near her children. She watched Sue-Ellen like a hawk, knowing only too well what some men would do to small children.

On rainy days they all

stayed inside, and Peewee would come to Joan’s part of the house. Peewee didn’t

cook. Her idea of preparing a meal was to take a thick wedge of bread and

spread jam and sour cream on it. That was her favourite thing to eat. But Joan

was an accomplished cook and Peewee loved to watch her prepare food. She often

made special dishes for Peewee: beef stroganoff and borscht, things that would

give her back a sense of home.

One night Jack was very drunk and got lost on his way home from the pub. He knocked on the door of somebody else’s house, then panicked and told them who he was. The neighbours told him how to get back to the house, but they rang a newspaper as soon as he’d left. Jack does not seem to have been a very good spy. Joan was certain then that it was his wife who had the brains, and who was the real catch for ASIO.

This is an edited extract from With My Little Eye by Sandra Hogan, Allen and Unwin, RRP: $29.99, available now.

Fetch your first 12 weeks for $12

Here at Crikey, we saw a mighty surge in subscribers throughout 2020. Your support has been nothing short of amazing — we couldn’t have got through this year like no other without you, our readers.

If you haven’t joined us yet, fetch your first 12 weeks for $12 and start 2021 with the journalism you need to navigate whatever lies ahead.

Peter Fray

Editor-in-chief of Crikey