It was a decision that caught the Coalition government of the day on the hop. Having condemned opposition leader Gough Whitlam as a dupe for visiting Beijing, then prime minister Billy McMahon had little choice but to declare that “his [Nixon’s] policy is ours”.

This left Australia and the United States in an ambiguous position that persists to this day. Officially, we do not recognise Taiwan as a sovereign state or even a separate entity, nor do we regard its elected officials as a national government. Yet practically we support it as an outpost of democracy, at a time when Beijing is becoming increasingly authoritarian, particularly in its approach to dissent and minorities.

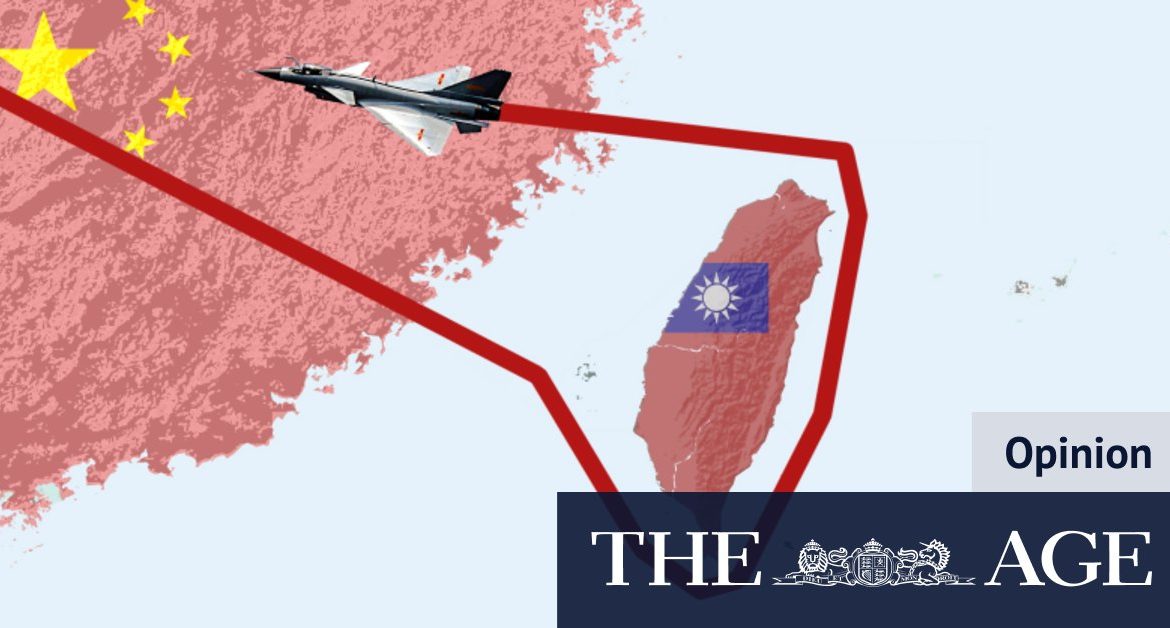

When relations with China were improving – with even Taiwan moving towards closer ties – this ambiguity could be papered over. But as relations deteriorate and Beijing pursues an increasingly aggressive regional policy, the question becomes: what are we willing or able to do to uphold Taiwanese self-determination?

Loading

After the Trump administration’s chest-beating and its ineffective trade war, our Asian allies will be watching closely to see if US President Joe Biden has a better formula for bringing China’s leadership to the table. When White House press secretary Jen Psaki used the phrase “strategic patience” – widely associated with Barack Obama’s approach to North Korea – to describe policy on China, alarm bells rang. It was soon renounced by a spokesman for the National Security Council, as national security adviser Jake Sullivan affirmed the need to “impose costs” for Beijing’s behaviour.

Mr Sullivan has also stressed the importance of incorporating European and Asian allies into what he called “a chorus of voices” to create “situations of strength”. While that may please foreign capitals after the jangling discords of the Trump presidency, there is still the question of what these voices will be singing or, as Ms Payne put it, whose language will be used.

With some China analysts saying we must be prepared to follow Washington into a war in defence of Taiwan if necessary, others warn that such a move would have even graver consequences than our commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan, it is essential that Mr Biden and his advisers recall the debacle of the Obama administration’s “red lines” on Syria and ensure that whatever approach the US decides to take is both consistent and clear to its allies.

For Australia, the challenge is finding a language on China relations it can share not only with its chief ally but with regional partners. Mr Biden’s unprecedented decision to invite Taiwan’s de facto ambassador, Hsiao Bi-khim, to his inauguration, like then president-elect Donald Trump’s 2016 phone call to Taiwanese leader Tsai Ing-wen, is a symbolic move awaiting a strategy. The Morrison government needs to work out and communicate to Australians where it will stand, so we aren’t caught on the hop again.

Note from the Editor

The Age’s editor, Gay Alcorn, writes an exclusive newsletter for subscribers on the week’s most important stories and issues. Sign up here to receive it every Friday.