Content warning: contains reference to family violence.

Daizy Maan is sitting comfortably on a sofa in a cottage nestled in the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges, about an hour from Melbourne.

The 26-year-old is sharing the space with friends she made only a week ago, often laughing and joking in a crisp Australian accent sprinkled with Punjabi – her language of origin. It’s a world away from the environment she grew up in.

Daizy’s family moved to Australia from India and she was born in the regional city of Griffith in New South Wales.

“Growing up, I have experienced violence and was conditioned to think that respect and obedience are the same two things,” she tells SBS News.

“But I was outspoken and rebellious.”

Her strong head, covered with messy curls, is an attribute of her indomitable spirit. As she shakes her hair free, she smiles.

“I also wanted to put forth my opinions,” she says. “But when they went unheard, I left.”

Daizy went to live with her older sister in Melbourne, but aspiring to be independent at only 16 proved tough.

She drifted, urging to belong, and hit rock bottom three years later; homeless, helpless, and reeling from a severe bout of depression.

“I felt like a lost teenager, a victim because of the instability I had experienced growing up.”

“I was conditioned to live and behave in a certain way. I felt like the entire world was pitted against me.”

I was conditioned to live and behave in a certain way. I felt like the entire world was pitted against me.

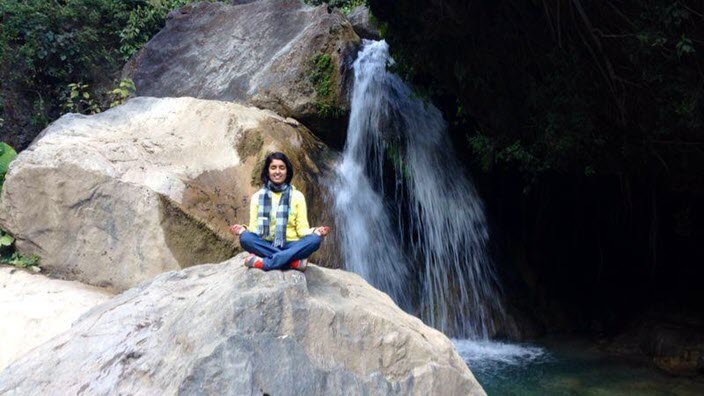

Daizy sought help from psychologists, then a conversation at a wedding she attended in India sent her packing to the Himalayas.

“I remember I was in Chandigarh [in north India] at a wedding … when a distant relative suggested I should try meditating in the Himalayas,” she says.

“I just shoved a few clothes in a bag and took a bus to Rishikesh, where I ended up in an ashram for 40 days doing meditation and practising yoga, which initiated my healing and changed my outlook towards life.”

Daizy says at that point she didn’t know what she wanted from life, but she was very clear about what she didn’t want.

“I didn’t want to be known as a victim,” she says.

“I didn’t want my entire identity to be about someone who had been abused. I wanted people to know me for my work, achievements and my campaign for social justice.”

‘To women, with love’

It was this experience that three years later – after 17 work experience placements and 14 volunteer jobs – inspired Daizy to set up a wellness space for women.

Soul House, a collection of cottages in the Victorian suburb of Belgrave, claims to be Australia’s first dedicated wellness and creative space for Indian, Pakistani and South Asian women.

Daizy says it is a safe and peaceful haven that empowers women and helps them to find themselves. For those who need it, it is also an opportunity to distance themselves from toxic situations.

“Women of South Asian backgrounds are often subjected to social conditioning, predominantly by men in their families. They are told ‘do this, wear that, marry him, study this’. There are also abusive environments. So, I concluded that there should be a place where we can live in peace.”

Daizy took to social media to raise close to $20,000 to begin the project, which can house four women at a time and is operated by volunteers.

“This is my gift to women with love, so that they can come here, get some physical and mental space from their abusive homes or disturbing situations where no one judges them for their choices,” she says.

“We don’t charge anything. We have a simple ‘pay whatever you feel’ system to ensure women who do not have financial means can also come and live here in these beautiful cottages surrounded by nature without any conditions or barriers.”

Daizy is clear though that Soul House shouldn’t be labelled as a shelter. Women needing specific, professional support with domestic or family violence and mental health should seek help elsewhere.

“There are already many organisations and government-funded shelter houses that are providing that kind of service to women in Australia,” she says.

But, she admits, “there’s a lack of space or programs that can provide a culturally sensitive environment to women of migrant backgrounds”.

Instead, Soul House offers workshops on meditation, mindfulness, keeping fit and financial planning.

“We live here, we talk, we read, we eat, and we share our stories. We also meditate and practice yoga. I often organise workshops and artist retreats giving residents a chance to share and learn new skills from each other.”

“I get so many random calls and requests from migrant women reaching out to me because they can relate to me, owing to our common background and similar experiences,” Daizy says.

“I want to make it easier for women to move out and move on.”

This story is part of the My Australia series, exploring identity and difference through the lives of extraordinary Australians. Read the full My Australia collection here.

Avneet Arora is a journalist with SBS Punjabi.

More information about Soul House can be found here.

If you or someone you know is impacted by family or domestic violence, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. The Men’s Referral Service provides advice for men on domestic violence and can be contacted on 1300 766 491. In an emergency, call 000.

Readers seeking support with mental health can contact Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. More information is available at Beyondblue.org.au. Embrace Multicultural Mental Health supports people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.