Then came the sucker punch.

“A month later he went for a chest X-ray for his heart, and they discovered the melanoma had spread to his lungs,” she said.

“He’d had no idea. He hadn’t been sick, he was living healthy and he had a bit of a ticker problem, he was 63 and went to get that checked out and found the cancer instead.”

Mr Wehl endured several operations over the next 11 months and the cancer spread through his organs and to his brain. He succumbed to it in February 2014.

Three of his seven grandchildren were born during his year of battle against the cancer, and Ms Cottrell said he was making time for them up until the end.

“It was a busy year for him,” she said. “And he was a farmer, he always said he had too much work to do to die. He worked bloody hard while going through surgeries and still made time for his grandkids.

“He had grand plans of taking them all camping on Moreton Island when they were older.”

Mr Wehl suffered from metastatic melanoma, an aggressive form of melanoma which killed 1375 Australians in 2020, according to figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

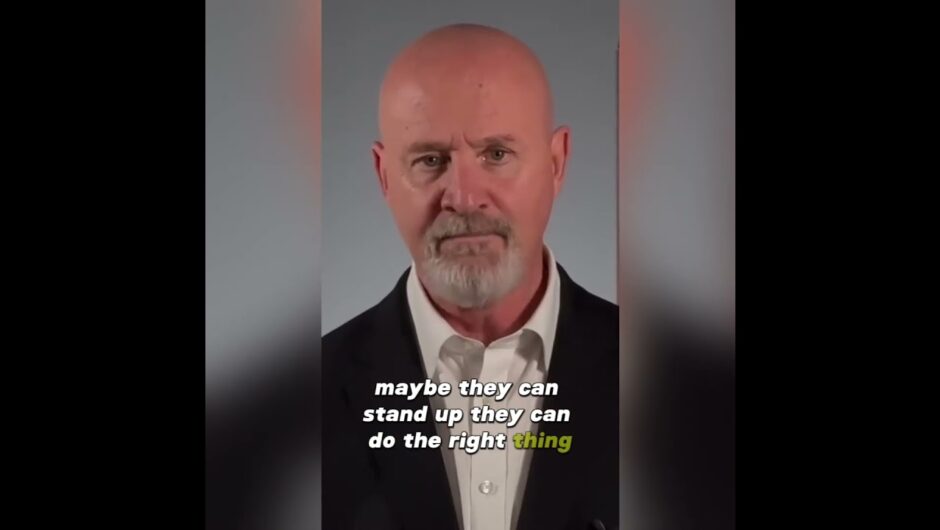

Associate Professor Jason Lee, who heads QIMR Berghofer’s epigenetics and disease group.Credit:QIMR

Researchers from QIMR Berghofer medical research institute believe they have developed a test they hope will get more people the treatment they need.

The use of immunotherapy to treat melanoma has grown exponentially in recent years, however some patients do not respond to the treatment.

QIMR associate professor Jason Lee said they had devised a way to test for a specific protein – LC3B – in cancer cells, which was associated with good responses to immunotherapy.

The study showed 95 per cent of patients with high LC3B levels were alive after three years, compared with 60 per cent of patients with low LC3B levels.

“Our ultimate goal is patients we identify to be very sensitive to immunotherapy, they can go and get that treatment, while the patients who are unlikely to respond to immunotherapy, we may be able to give them alternate therapy,” Professor Lee said.

The team also identified that some metastatic melanoma patients had high levels of the G9a enzyme in their cancer cells, which reduced the ability of immune cells to reach the tumour.

“We believe blocking the activity of G9a enzymes will in turn raise the level of LC3B protein, making patients more responsive to immunotherapy and possibly even other treatments.

Loading

“We are actively working to develop a drug that can be used to treat patients, but this will take time, as the drug we used in our studies isn’t commercially available.”

Alice Cottrell says she wished the researchers well, and hoped they gave other melanoma sufferers a chance her father never had.

“We’re finding out more every day that there are good cancers to get and bad cancers to get, and the one Dad had was definitely a bad one,” she said.

“And I know they’ve had lots of breakthroughs in melanomas but very few in this type, so it’s great to see there may be some hope for people in Dad’s position.”

The QIMR research has been published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research.

Stuart Layt covers health, science and technology for the Brisbane Times. He was formerly the Queensland political reporter for AAP.

Most Viewed in National

Loading