Matt Scullion learned long ago that it’s best to answer the phone when Lenny Pascoe’s name flashes up.

Australia Day last year was no exception. The singer-songwriter was at the Tamworth Country Music Festival when he took a call from the former Australian fast bowler.

“Mate, I’m here with Les Knox and I’ve got a great story to tell you,” is how Pascoe began.

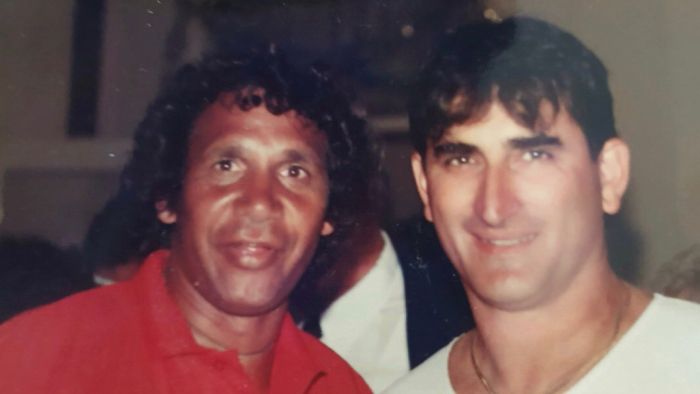

Knox is a Goomilaroi elder, a former grade cricketer at North Sydney and a mainstay of the New South Wales cricket administration, having helped start the state’s Aboriginal cricket association in 1983. He’s been Pascoe’s companion through plenty of cricket adventures.

That day in 2020, Knox and Pascoe had gathered in Narrabri for a reunion of the surviving members of the 1988 Aboriginal Australians squad — Knox’s brainchild — which toured England, retracing the steps of the pioneering 1868 team. Len had played a small role, turning out in Bob Hawke’s Prime Minister’s XI team that faced the Aboriginal squad in an exhibition game before their departure.

Pascoe and Knox wondered: books have been written about the trailblazing Indigenous team, but why not a song?

“Len proceeded to tell me the story of this 1868 team,” Scullion says.

“Len said he thought I should write a song about it, and I said, ‘So do I’.”

With the permission of Knox and Richard Kennedy, a descendent of 1868 player Yanggendyinanyuk (known as Dick-a-dick), Scullion spent four months labouring over the lyrics, steeping himself in the team’s history before setting pen to paper.

Scullion pulled off a feat in fitting so many characters and events into four and a half minutes: the unlikely rise of 13 stockmen and station hands to the status of sporting pioneers; their nervous passage to England; the packed stands for the team’s 47 matches, including an appearance at Lord’s; the obvious brilliance of leading light Johnny Mullagh; the total indifference of the public upon the team’s return to Sydney.

“It took me about four months to write it,” Scullion says.

“I then sent it to Richard Kennedy. Being a whitefella, I wanted to get pronunciations of names and places right. It’s important to get it right. There is no room for artistic licence with a song like this.”

At the studios of Shane Nicholson, the song, simply titled 1868, came to life. For three weeks it topped the Australian country charts based on word-of-mouth promotion alone.

“It turned out really good,” Knox says.

“I got this feeling when I heard it, even though I’m not from the same area as the players, I thought, ‘He’s got it right and it sounds good’.”

Loading

Pascoe, too, was thrilled.

“I just thought it was amazing that nobody had written a song about it,” he says.

He knows the power of song better than most cricketers.

“Pascoe’s makin’ divots in the green” went the famous line of ‘C’mon Aussie, C’mon’, the anthem of World Series Cricket. It gained him as much notoriety as the 119 international wickets bowling alongside Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson in the late 1970s and early 80s, all chest hair and gold chains.

Yet there was always something a bit different about Lenny. In a recent book about Sydney University’s Sydney grade premiership of 1976-77, a surprised opponent appraises the man behind the barrages of bouncers: “I realised he’s not only clever but sensitive.”

Those who know the private Len will not be as surprised to discover involvement in the 1868 song. Pascoe has maintained a lifelong passion for involving Indigenous Australians in the game, as a coach and entertainer.

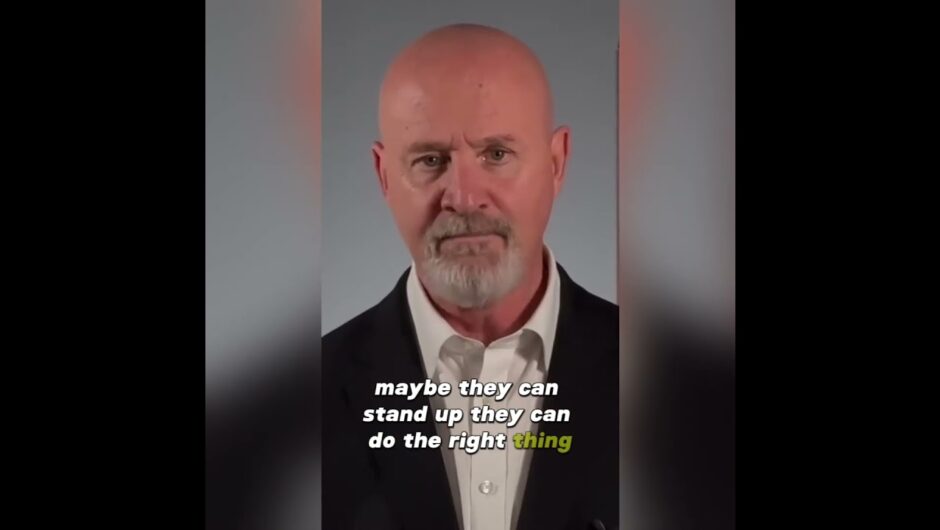

“I’ve been coaching cricket for many years now, and I feel a responsibility to teach the sport but to be a good role model,” Pascoe says.

“It’s been an ongoing process for a long time.”

In recent times, Pascoe has also wondered a little more deeply about his time at cricket’s pinnacle.

“I was one of the first non-Anglo players to play for Australia, other than the Aboriginals,” he says of his Macedonian and Vlasi heritage (he was born Leonard Durtanovich).

“I don’t know if I handled it all that well. I didn’t realise the enormity of it at the time. I was too wrapped up in my own world.”

He wishes there was more respect for the achievements of the 1988 players.

“They should get some recognition too,” Pascoe says.

“We’ve got Jason Gillespie, Scott Boland, Dan Christian in the men’s teams. We have players in the BBL. But the guys from 1988 have been forgotten.”

Knox too regrets that the Indigenous players who represented the Australian Aboriginal XIs on tours of England in 2018 weren’t told about the path forged by his squad.

“I was a bit cranky,” Knox admits.

“They were told they were the first team to go back since 1868. They didn’t know about the history of the 1988 side.”

Scullion best summarises the man who has become his booking agent and most enthusiastic backer: “Lenny’s a real ideas bloke and if he likes something, he’s all over it.”

One of those ideas is for every state to have an Indigenous cricket academy, but Len is happy to chip away at grassroots level, realistic that plenty of people make big promises and don’t deliver.

“Sometimes people have their heart in the right place, but they don’t understand,” Pascoe says.

“I don’t profess to understand, I just say that I’m prepared to learn. Indigenous people get knocked down. Every opportunity I’ve had to be in contact with Indigenous sportspeople, they’ve been very impressive.”

At 71, Pascoe finds himself in a philosophical phase. He sees symbolism in the role of Indigenous cricket when the two health crises of his life struck: few realised he was battling a putative brain tumour when he played in the 1988 game; the 1868 song has given him a boost in the wake of triple bypass surgery.

The latter also reaffirmed Pascoe’s views of the world around him, and a resolve to make people “think a little differently”.

“My cardiologist was of Asian background,” Pascoe says.

“My surgeon was of Indian background. The anaesthetist was a New Zealander. The nurse was Malaysian. You realise that we’re very lucky in Australia to have these wonderful people in this country. How could you be racist?”

And how did Pascoe react when he first listened to 1868?

“He totally freaked out when he heard it,” Scullion says.

“He wanted me straight in at the Bradman Museum to play it.”

The pair will reunite to do just that in April.

There were hopes that it could be played two months ago during Australia’s Boxing Day Test against India, to coincide with the inaugural presentation of the Johnny Mullagh Medal, but COVID-19 scuppered that. Instead, three weeks after the song’s release Scullion played it at the second Twenty20 international at the SCG.

“There is another side to the game than how many wickets and how many runs you got,” Pascoe concludes.

“When you add it up and ask, ‘Why have I been given this opportunity?’ I look back and take a lot of pride in the fact that I survived it and left my mark. But what’s the point of that if you can’t do something with it?