More than a week since news of the incident broke, we’ve got nothing but dishonest deflection from the government — and a lot of unanswered questions.

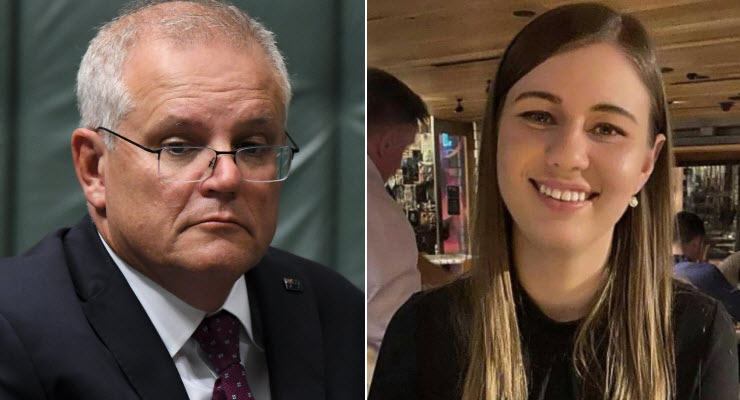

When Brittany Higgins alleged she’d been raped by a male staffer in Parliament House, it could have been an opportunity for Prime Minister Scott Morrison to take a principled stand on a toxic workplace culture.

Instead, in the 10 days since, we’ve heard mealy-mouthed statements and dishonest deflection from the government — and a lot of unanswered questions.

We still don’t know who knew what about the incident and when. We don’t know why Morrison knew well after several of his ministers and staffers in his office. We don’t know what happened to the alleged perpetrator after the night in question, or why police and public servants bungled so much.

How many ministers knew before the PM?

Morrison maintains he knew nothing of Higgins’ allegations until the news first broke last Monday, February 15. But plenty in his government knew at least something. Senate President Scott Ryan knew about “an incident” the week after it allegedly happened, in March 2019. Speaker Tony Smith found out some detail in April that year. Ryan says he only knew the full details on Friday, February 12.

Defence Minister Linda Reynolds, Higgins’ boss at the time, knew the details within a week when she had a meeting with her staffer in the room where the alleged assault occurred. She’s been repeatedly questioned about what she knew, and has given conflicting accounts of meetings with police. Reynolds would’ve faced even more scrutiny at the National Press Club yesterday, but was admitted to hospital on the advice of her cardiologist.

Employment Minister Michaelia Cash knew about an “unspecified incident” in late 2019 when Higgins began working for her. She became aware of the rape allegations on February 5, 10 days before Morrison.

Yesterday Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton revealed he knew as well. He’d been tipped off by the Australian Federal Police on February 11, under “sensitive information” guidelines which obliged them to inform the minister when Higgins told them she was considering reopening the investigation.

After evading journalists, this morning Dutton defended his decision not to tell Morrison. He also described the incident as “he said, she said” — because the man is all class.

So why did none of these ministers feel the need to inform the prime minister? And if they knew, how many of their senior staff also knew? Perhaps at this point it’s more relevant to ask who in the government didn’t know about the incident before Morrison.

What happened in the prime minister’s office?

The official line from the prime minister’s office is it didn’t know details until February 12 when it first got questions from news.com.au. For some reason, staff didn’t tell their boss.

Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese says it “doesn’t seem plausible” Morrison didn’t know about the incident until last Monday because plenty of his staffers seemed to. But how many staffers knew, and what level of detail, is also unclear.

Fiona Brown, Reynolds’ chief of staff at the time of the incident, knew within a week. She now works in Morrison’s office. On Monday Guardian Australia reported another staffer now in Morrison’s office knew about the alleged perpetrator being fired.

There’s also evidence the PM’s office knew much earlier. Text messages indicate a friend of Higgins had informed someone in the office back in 2019. And some of Morrison’s most senior staff seemed to know something.

Higgins says the prime minister’s principal private secretary Yaron Finkelstein contacted her on Whatsapp for a “check-in” right after the ABC’s “Inside the Canberra Bubble” Four Corners aired last year. Finkelstein and Morrison deny this. Chief of staff John Kunkel was in the meeting where the alleged perpetrator was fired, but says he didn’t know about the rape allegations until February 12.

Morrison says everything’s fine in his office. But the only explanation for all this is many of his staffers have spent a lot of time with heads buried in the sand.

The alleged perpetrator

We know the alleged perpetrator’s employment was terminated days later but only for the “security breach” of being in parliament after dark.

The government won’t say whether it provided him with a reference or termination payout. And although his parliamentary access was cancelled, the government couldn’t confirm whether he’d returned as a visitor.

Since leaving parliament, he’s worked at a major lobbying company, and a large corporation from which he was recently stood down. And including Higgins, four women have made sexual assault allegations against the man.

Five reviews

The Morrison government has announced five inquiries. As Crikey reported this week, none really address the key question of how so many people knew about the incident without doing anything.

Morrison also refuses to confirm whether he will release a report by Phil Gaetjens, his former chief of staff and now secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, into what his office knew.

The bungling

Finally, if we go back to the aftermath of the alleged rape, there’s plenty more which doesn’t stack up. Why did the Department of Finance claim Higgins was offered an ambulance after being found in the office, something disputed by her and the Department of Parliamentary Services?

Why did Finance send steam cleaners into the office? Why, in April 2019, did Belconnen police say they were struggling to locate CCTV footage from Parliament House when Department of Parliamentary Services later said police did see it?

And why, above all, did so many people seem to know more about Higgins’ alleged rape than she did?

Inoculate yourself against the spin

Get Crikey for just $1 a week and protect yourself against news that goes viral.

If you haven’t joined us yet, subscribe today to get your first 12 weeks for $12 and get the journalism you need to navigate the spin.

Peter Fray

Editor-in-chief of Crikey