news, latest-news,

A bumblebee may be no longer than an inch, but its tiny brain – and ability to learn on the fly – could hold a key secret to developing the next generation of autonomous drones. An international study led by researchers from UNSW Canberra found that when faced with an obstacle or small gap, bumblebees had an acute awareness of the dimensions of the gap and their own bodies and could reorient themselves in a number of ways to pass through. Research lead author Dr Sridhar Ravi said applications of the research could allow drones to self-learn and complete automated tasks with “little processing power”. “Insects are fantastic models for robots because they have exceedingly small brains and yet they’re able to perform overly complex tasks,” he said. “Our challenge now is to see how we can take this and apply a similar coding to future robotic systems, enhancing their performance in the natural world.” The research – a collaboration between UNSW, Bielefeld University, The Max Planck Institute, Brown University and The University of California – placed bumblebees in a tunnel with a series of gates featuring different sized holes, and examined how the bees sized up each hole and changed their flight path accordingly. Just by looking at the hole, the bees were able to correctly judge how their own dimensions related to its size and shape and alter their speed, approach and posture accordingly – even flying through sideways when the opening was smaller than their wingspan. “Previous research had indicated that complex processes, such as the perception of self-size, were cognitively driven and present only in animals with large brains,” Dr Ravi said. “However, our research indicates that small insects, with an even smaller brain, can comprehend their body size and use that information while flying in a complex environment.” Bumblebees were chosen for the study because there could be a significant size variation between bumblebees even within the same hive – meaning rather than being hardwired to know how big it was, each bee was individually aware of its own size. The bumblebees were also disadvantaged by their monocular vision: “Even though insects have two eyes, their eyes are spaced too far apart, so unlike humans they can’t compare information to get an estimate of depth,” Dr Ravi said. That was where the bumblebees brought out their secret weapon – lateral peering. “If you close one eye and move your head from side to side, objects that are close to you move a lot more than objects that are further away from you,” Dr Ravi said. And the bees would use the same principle when approaching a gap, moving their body from side to side to gauge and process its width and depth. Dr Ravi said while drones were previously programmed to perceive their environment in hardwired absolutes – to measure the dimensions of spaces and compare them against their own – this new research would allow drones to navigate the world in terms of “affordances”. “Humans perceive the world in what the environment affords us – we perceive a doorway not in terms of its absolute size but whether or not the doorway can afford us passing through,” he said. Understanding the affordances of an environment was previously thought to only be a trait of more developed vertebrates – but the study’s findings established animals much further down the evolutionary line with much simpler brains could do the same. “It gives us inspiration to see how we can automate this process, how we can make a robot that will automatically learn its own size based on its affordances,” Dr Ravi said. And bumblebees weren’t the only insects useful to developing drones and other robot technologies – because of their small brains, insect behaviour of all sorts was perfect for mimicry in robots. “A very good example is on any given day you open a bottle of wine and all of a sudden you will see a fruit fly from out of nowhere tracing the bottle,” Dr Ravi said. “This is a classic example of an insect that is extremely tiny but so attuned to tracking it can teach us how to perfect a system to track and trace.” And it was understanding the simplicity of the bumblebee that would be key in developing drones and autonomous vehicles in the future. “An animal that is so small with essentially a single eye is able to accomplish such complex tasks because it takes advantage of all these simple activities,” Dr Ravi said. “The main takeaway is the ingenuity of doing complex things with relatively simple tools.”

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/8WgcxeQ6swJGymJT6BMGEL/ff72f03a-d4c6-4bf2-bead-c03c41c99cf5.jpg/r17_247_6921_4148_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

A bumblebee may be no longer than an inch, but its tiny brain – and ability to learn on the fly – could hold a key secret to developing the next generation of autonomous drones.

An international study led by researchers from UNSW Canberra found that when faced with an obstacle or small gap, bumblebees had an acute awareness of the dimensions of the gap and their own bodies and could reorient themselves in a number of ways to pass through.

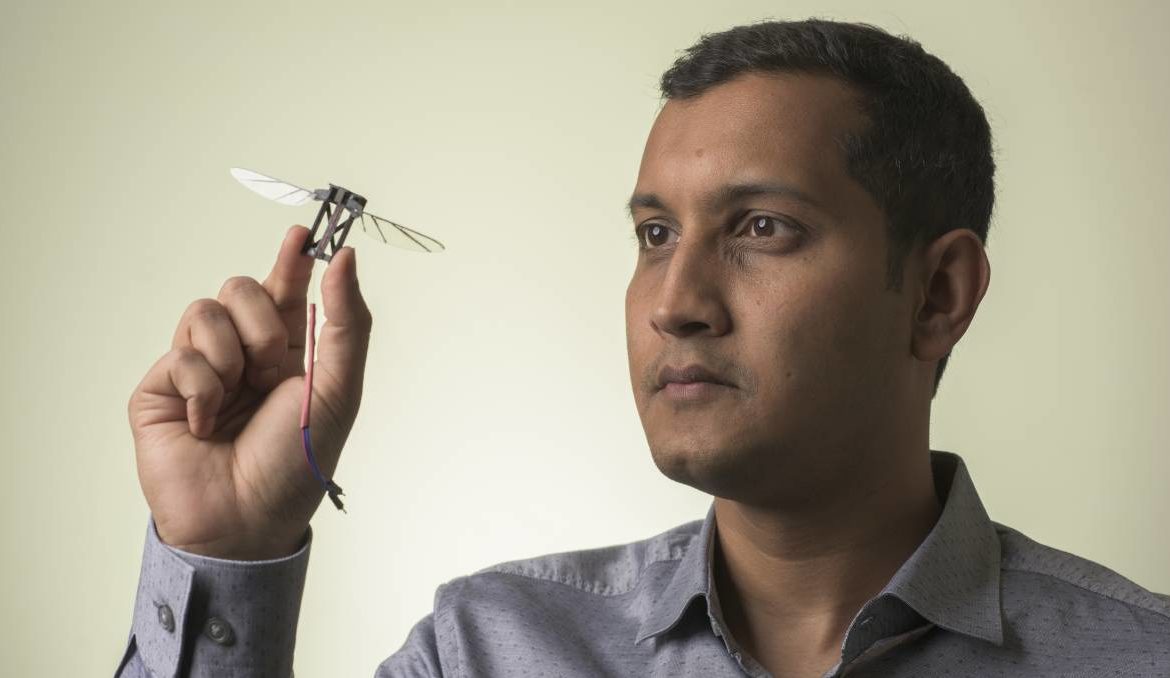

Research lead author Dr Sridhar Ravi said applications of the research could allow drones to self-learn and complete automated tasks with “little processing power”.

“Insects are fantastic models for robots because they have exceedingly small brains and yet they’re able to perform overly complex tasks,” he said.

“Our challenge now is to see how we can take this and apply a similar coding to future robotic systems, enhancing their performance in the natural world.”

The research – a collaboration between UNSW, Bielefeld University, The Max Planck Institute, Brown University and The University of California – placed bumblebees in a tunnel with a series of gates featuring different sized holes, and examined how the bees sized up each hole and changed their flight path accordingly.

Just by looking at the hole, the bees were able to correctly judge how their own dimensions related to its size and shape and alter their speed, approach and posture accordingly – even flying through sideways when the opening was smaller than their wingspan.

“Previous research had indicated that complex processes, such as the perception of self-size, were cognitively driven and present only in animals with large brains,” Dr Ravi said.

“However, our research indicates that small insects, with an even smaller brain, can comprehend their body size and use that information while flying in a complex environment.”

Bumblebees were chosen for the study because there could be a significant size variation between bumblebees even within the same hive – meaning rather than being hardwired to know how big it was, each bee was individually aware of its own size.

The bumblebees were also disadvantaged by their monocular vision: “Even though insects have two eyes, their eyes are spaced too far apart, so unlike humans they can’t compare information to get an estimate of depth,” Dr Ravi said.

That was where the bumblebees brought out their secret weapon – lateral peering.

“If you close one eye and move your head from side to side, objects that are close to you move a lot more than objects that are further away from you,” Dr Ravi said.

And the bees would use the same principle when approaching a gap, moving their body from side to side to gauge and process its width and depth.

An animal that is so small with essentially a single eye is able to accomplish such complex tasks because it takes advantage of all these simple activities.

Dr Sridhar Ravi

Dr Ravi said while drones were previously programmed to perceive their environment in hardwired absolutes – to measure the dimensions of spaces and compare them against their own – this new research would allow drones to navigate the world in terms of “affordances”.

“Humans perceive the world in what the environment affords us – we perceive a doorway not in terms of its absolute size but whether or not the doorway can afford us passing through,” he said.

Understanding the affordances of an environment was previously thought to only be a trait of more developed vertebrates – but the study’s findings established animals much further down the evolutionary line with much simpler brains could do the same.

“It gives us inspiration to see how we can automate this process, how we can make a robot that will automatically learn its own size based on its affordances,” Dr Ravi said.

And bumblebees weren’t the only insects useful to developing drones and other robot technologies – because of their small brains, insect behaviour of all sorts was perfect for mimicry in robots.

“A very good example is on any given day you open a bottle of wine and all of a sudden you will see a fruit fly from out of nowhere tracing the bottle,” Dr Ravi said.

“This is a classic example of an insect that is extremely tiny but so attuned to tracking it can teach us how to perfect a system to track and trace.”

And it was understanding the simplicity of the bumblebee that would be key in developing drones and autonomous vehicles in the future.

“An animal that is so small with essentially a single eye is able to accomplish such complex tasks because it takes advantage of all these simple activities,” Dr Ravi said.

“The main takeaway is the ingenuity of doing complex things with relatively simple tools.”