A century ago, on November 21, 1920, fans came in their thousands from all across Dublin and beyond to stand on the terraces of Croke Park.

Key points:

- On Sunday, November 21, 1920, 14 people attending a football match at Croke Park in Dublin were killed by British forces

- Tipperary player Michael Hogan was one of the 14 people killed, along with three children

- The Gaelic Athletic Association is commemorating the centenary of the massacre by remembering the 14 victims

They were there to see Dublin’s Senior Gaelic Football team take on Tipperary in a “Great Challenge Match”, the playing of which had already created quite a stir.

After all, the Irish public had been relatively starved of major sporting occasions that year.

The progress of the 1920 All Ireland Senior Football Championship — the blue riband event of the Irish sporting summer — had been stymied by the pressures of Ireland’s War of Independence, so much so that the 1920 Championship would not end up being completed until 1922.

It was supposed to be a day where the troubles of a nation could be momentarily forgotten.

Instead, November 21 would become indelibly marked as one of the darkest in Irish history.

Shortly after the ball was thrown in to start the game, ranks of police and soldiers marched on the ground and opened fire on the crowd.

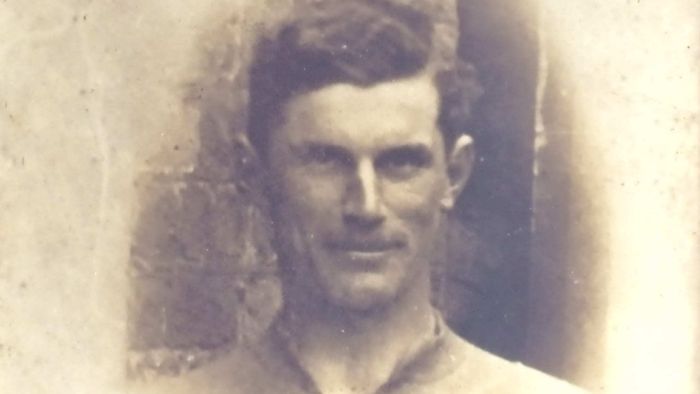

Fourteen civilians died in the massacre, either directly from the gunfire or in the panic of the ensuing crush to escape — including Tipperary corner back Michael Hogan.

The youngest victim, Jerome O’Leary, was 10 years old.

Now, 100 years on, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) is pushing to remember those that went to the football and never came home.

Bloody Sunday

In the 1920s, Ireland was in the midst of a torrid war for independence from Britain.

The war had been typified by a brutal guerilla conflict of increasingly rabid tit-for-tat exchanges across the Irish countryside between the ruling British police force — supplemented by auxiliary forces fresh from World War I — and the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Atrocities and reprisals stacked up, but November 21’s bloodshed marked a dramatic turn in the war.

At around 9:00am, an IRA cell launched a coordinated set of attacks on alleged British agents in Dublin, killing 14 men across the city — some in front of their wives and families — causing enormous panic to ripple through the British establishment.

It was accepted by the IRA that striking at the heart of the British intelligence operation in such a dramatic way would surely invite a response.

The large-scale gathering of GAA supporters at Croke Park that afternoon proved simply too large an event to ignore for the authorities.

Although the GAA was ostensibly an apolitical association, British authorities felt there was enough about its activities that showed it was partisan.

The GAA remains to this day a preserve of Irish culture by promoting Ireland’s domestic indigenous sports — most notably Gaelic football and hurling.

The association also existed to “actively support” the Irish language, Irish dancing, music and other elements of Irish culture.

The IRA asked the Luke O’Toole, general secretary of the GAA, to cancel the game, but he did not want to compromise the body’s status as a sporting organisation by reacting to what was seen as a political issue.

So the game went ahead in front of a then-massive crowd of around 15,000 people.

British soldiers — lead by the infamous Black and Tans — and Royal Irish Constabulary policemen were sent to Croke Park, where they were told to search the crowd for any members of the IRA cell that had perpetrated that morning’s attacks and to confiscate any weapons.

However, instead of simply pausing the game as they were ordered, the soldiers opened fire.

Over the next 90 seconds, 14 people died, with many more suffering injuries.

The official account said police were fired upon first, however modern research has found little evidence this was the case.

When Irish MP Joe Devlin raised a question about the massacre in Westminster, the argument that followed descended into a fist fight.

After the shock of Bloody Sunday, the War of Independence in Ireland raged on for another year.

Subsequent to the end of British rule, the country lurched into a full-blown Civil War between 1922-23, the effects of which are still apparent today.

Croke Park: ‘More than a pitch’

Cian Murphy, the secretary of the GAA history committee, has helped plan the commemoration events for the centenary of Bloody Sunday.

He said the events changed the GAA and its status in Irish culture.

“The attack on Croke Park and, by extension the GAA, put the Association on a different footing in the Irish consciousness,” Mr Murphy said.

“The GAA was and still is a sports-first body with a non-political stance.

It also changed the GAA’s relationship with its opulent home in the heart of Dublin, Croke Park.

With a capacity of 82,300, Croke Park is one of Europe’s largest sporting venues.

It has been the home of Gaelic games in Ireland since shortly after the GAA was formed in 1884, with the first All Ireland final taking place there in 1896 — and almost every year since.

Bloody Sunday ensured that it would never again be just be a sporting venue.

“In sporting terms [Croke Park is] the national symbol of Ireland,” Mr Murphy said.

“For all our pride in the great sporting cathedral that is Croke Park, there is the realisation that it isn’t ‘just a pitch’.

“It has a history and a heritage and is for many people sacred ground, because of the sporting gods who walked there, but also because of November 21, 1920.

“The GAA will never leave Croke Park and nor would we want to. We need to keep it and honour it for all its history.”

Bloody Sunday’s historical reach

The events of Bloody Sunday helped make Croke Park a revered venue in Ireland’s sporting consciousness.

However, there were concerns the venue’s sanctity could become befouled when one of the GAA’s most fundamental rules was relaxed in 2007.

Rule 42 prohibits the use of GAA property for games with interests in conflict with the interests of the GAA — colloquially, this is known as a ban on “garrison games” such as rugby or football.

With Irish Rugby homeless due to the redevelopment of its Lansdowne Road HQ, the GAA was approached to lease its grounds for its upcoming Six Nations matches.

One of the first matches Croke Park was set to host was Ireland against England — the most sensitive of fixtures, burdened with the weight of so much violent history.

“To have an English team play and have ‘God Save the Queen’ played on the site where people were murdered by Crown Forces was hugely emotive and divisive for some,” Mr Murphy said.

Former GAA player JJ Barrett found it too much of an affront and asked for the Croke Park-based GAA museum to return his family’s 23 All Ireland medals that were on display.

Mr Murphy argues that the vote to open up Croke Park, which he said was driven by grassroots clubs within the organisation, was an important part of the healing process.

“Opening Croke Park to those games was, for many, a sign of the times, an important part in the new emerging Ireland where the Good Friday Agreement was upheld and there was peace in the North,” he said.

The first prospective pinch point, the emotive singing of God Save the Queen, went off without a hitch, while the extraordinarily passionate reply of Amhrán na bhFiann that followed was so powerfully intense that it moved some of the players to tears.

Loading…

The actual game went even better, as the Irish steam-rolled the English by a record score of 43-13.

Michael Hogan honoured, but other victims forgotten

The tragic events of Bloody Sunday have been chronicled superbly by Irish Times journalist Michael Foley in his excellent book, The Bloodied Field.

He reveals the myriad of storylines that emerged from a complex and horrific day, be it the British soldier who was saved by Patrick O’Dowd before he was shot, through to Dublin goalkeeper Johnny McDonnell, who had been involved in the IRA attacks earlier that day.

The story that everyone knows is that of Michael Hogan, with one of the main grandstands named in his memory in 1926.

However, in time, the other victims largely became nameless casualties.

Mr Murphy said he hoped that the research completed by Foley and the GAA in recent years had helped heal old wounds.

“It’s always hard to put today’s norms into yesterday’s reality,” Mr Murphy said.

“In 1920, the GAA was trying to exist with the country at war and navigate a path through that while trying to keep politics from dictating its direction.

“This manifests itself in how little we knew of our 13 civilians killed there for a long time.

“Michael Foley’s research enabled the GAA in recent times to trace those roots and reconnect with families of the victims of all 14 and I hope it has helped bring some closure to them.”

The Bloodied Field

It was the publication of Mr Foley’s book in 2013 that promoted action from the GAA in terms of recognising the other victims of the tragedy.

The relatives of one of the victims, Jane Boyle — who was due to be married the week after Bloody Sunday and was, instead, buried in her wedding dress — got in contact with the GAA to seek assistance in putting a headstone on her unmarked grave, something that was realised on November 21, 2015, 95 years after she died.

Eight of the victims were buried in unmarked graves, something the GAA has made a point of addressing in recent years.

“Knowing that there were seven more of our dead in unmarked graves, the GAA Management Committee sanctioned the Bloody Sunday Graves Project, which contacted families and assisted in erecting headstones where needed,” Mr Murphy said.

Loading

COVID-19 has put paid to many of the GAA’s plans for the centenary commemorations, but there will still be events taking place on the day.

“We had planned a Dublin vs Tipperary football game but that is not possible as the GAA season is still on,” Mr Murphy said. The GAA season would normally conclude in September.

“However, November 21 is a match day with the Leinster football final [featuring heavy-favourites Dublin against Meath] — and even though we cannot have spectators there we will gather and have a torch lighting and wreath laying ceremony and remember our dead.”

In lieu of that commemorative match against Dublin, Tipperary will wear a replica green and white kit in its Munster Senior Football Final against Cork on Saturday.

The GAA also has dedicated a website to the victims, as well as commissioning podcasts, radio programmes and a television documentary.

A new memorial is also planned for Croke Park, post-COVID.

“What matters now is that we ensure that Bloody Sunday isn’t a faceless line in history,” Mr Murphy said.

“The 14 dead are not a statistic, and we remember them by actions not words. Eli Weisel said, in 1968 when winning the Nobel Prize, ‘to forget your dead is akin to killing them a second time’.

“These were our people, who went to one of our games and never came home.