The US congress is working through a bill that would break up Facebook, potentially forcing the tech behemoth to spin out Instagram and WhatsApp and limiting acquisitions. All the other billionaires are dicking about in space — perhaps deciding that this reality isn’t all that much fun.

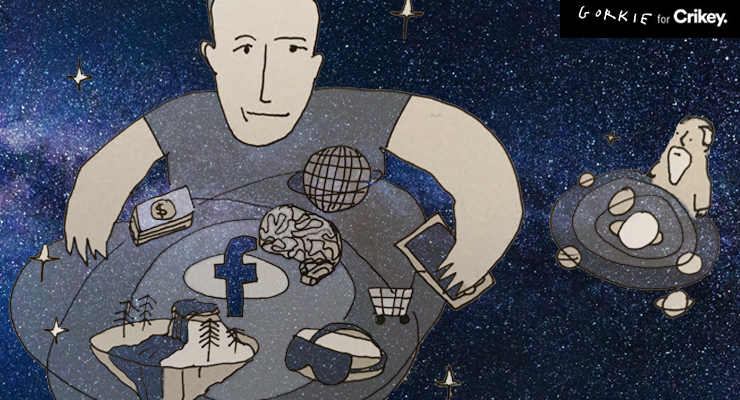

But Mark Zuckerberg — when he’s not pondering the meaning of America on his floating surfboard — is planning to retreat into the metaverse. He’s told Facebook employees his ambition to go well beyond the company’s reach to something genuinely ubiquitous: the metaverse, what he calls “the successor to the mobile internet”.

“What I think is most interesting is how these themes will come together into a bigger idea,” Zuckerberg said in his remote address. “Our overarching goal across all of these initiatives is to help bring the metaverse to life.”

In an interview with The Verge, Zuckerberg — famously adept with the concept of irony — said: “We’re basically mediating our lives and our communication through these small, glowing rectangles. I think that that’s not really how people are made to interact.”

The term “metaverse” was coined in Neal Stephenson’s 1992 sci-fi novel Snow Crash — long a cult favourite in Silicon Valley. It refers to an alternative digital reality, a shared online space where the physical and virtual converge.

A base understanding could be provided by films like The Matrix or eXistenZ, full realties that one physically enters, or virtual spaces like Second Life. But it’s more than that.

Among his seven preconditions for a metaverse, venture capitalist and former head of strategy for Amazon Studios Matthew Ball says a metaverse “never ‘resets’ or ‘pauses’ or ‘ends’, it just continues indefinitely”, it will “be a living experience that exists consistently for everyone and in real-time” and will “be an experience that spans both the digital and physical worlds, private and public networks/experiences, and open and closed platforms”.

Forbes illustrates it with the example of being out on a walk and suddenly remembering something you need — a vending machine appears with a variety of that product.

Facebook is far from the only company attempting to create and commercialise such a place. Google, Samsung, Epic Games, essentially every major tech company are competing to create something similar.

Indeed we’re seeing a lot of step towards metaverse-style events. In April 2020, Epic’s Fortnite held a Travis Scott concert that had more than 12 million concurrent views. In November 2019, Scott Belsky from Adobe gave a pitch for Aero, the company’s augmented reality software, so uncannily Black Mirror-like it’s almost surprising when he doesn’t explore its potential application as a method of punishment for murderers.

Indeed, just like seemingly every development with the same gee-whiz marvelling at the boundless possibilities of it all that tech billionaires like to frame these discussions. Yet anyone who’s read The New York Times cybersecurity reporter Nicole Perlroth bone-chilling This is How They Tell Me the World Ends might question the wisdom of sinking yet more of the fabric of life into the “internet of things” (or as our Bernard Keane puts it, the “internet of shit“) already, as she puts it, the world’s biggest target for cyber attacks.

What of the mental health implications of accelerating the immersion in schizophrenic virtual worlds eell under way on social media (elegantly sketched on Bo Burnham’s “Welcome to the Internet“)? What of surveillance? The already blurring lines between home and work?

The Forbes piece on the concept — which looks in detail at how a metaverse could affect every facet of life, and doesn’t appear to see anything all that ominous in any of it — tells us unequivocally, the metaverse is coming.

“Now the question is,” the piece brightly concludes, “how are you getting ready?”