It took 43 days since those first cases for NSW Chief Health Officer Dr Kerry Chant to say she was confident the Avalon cluster on the northern beaches had been brought under control on Wednesday.

Loading

Sunday’s two-week zero streak comes 40 days after NSW Health reported a patient transport worker within the hotel quarantine system had also tested positive on December 22, sparking a cluster in Berala in western Sydney.

That compared to the 116 days it took for health authorities to bring NSW’s case numbers back to zero after detecting 155 cases in two weeks following the Crossroads Hotel superspreader event in Casula in July amid Victoria’s second wave.

Why health authorities were able to extinguish these latest outbreaks considerably faster than Sydney’s mid-year clusters is far from clear, but several factors were likely responsible, clinical epidemiologist at the University of Sydney Dr Fiona Stanaway said. The most glaring was the decision to lock down the northern beaches.

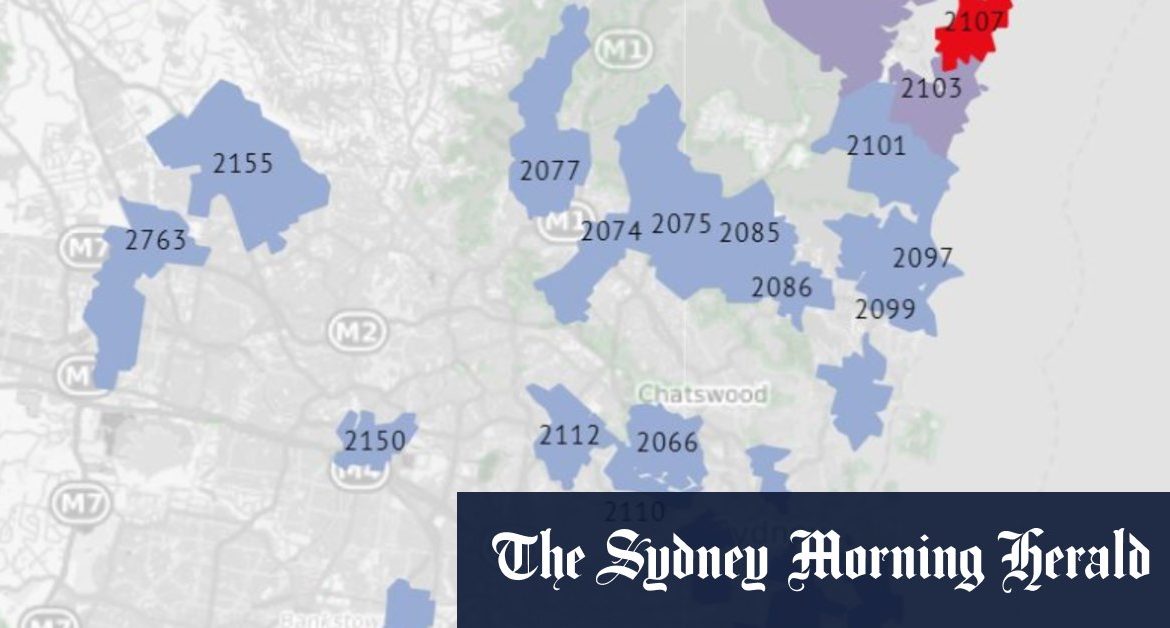

“That area was effectively sealed off, and what I understand about those suburbs is that people in the northern beaches stay in the northern beaches, as opposed to a suburb where a lot of different people are coming through and able to spread is more widely.”

The latter describes the location of the Casula cluster – a busy transport hub – from which multiple large clusters were seeded across Sydney, including more than 100 cases linked to two Thai Rock restaurants that were later traced back to Casula via genomic sequencing.

“There was also an amazing response to the call for testing during the northern beaches outbreak, which helped identify what was going on early, and what might help stop it,” Dr Stanaway said.

The time of year may have had an impact. The mid-year outbreaks occurred in winter when people were more likely to gather indoors – posing a higher risk of transmission than outdoor gatherings in summer, Dr Stanaway said.

Health authorities had a key advantage once the Berala cluster was detected: they knew the source of the cluster.

“Having already identified the patient transport workers and the link to hotel quarantine, hopefully they were then able to find most people linked to those few transmission events,” most notably the Berala BWS exposure site, Dr Stanaway said.

“The worry about Berala is that [current] testing rates aren’t high so there is a risk of low level transmission and another cluster popping up,” she said.

Epidemiologist and head of the public health interventions research group at UNSW’s Kirby Institute Professor John Kaldor said there were some strong similarities and clear differences between the Crossroads and Avalon clusters. Firstly, multiple transmissions in each cluster occurred on a single evening at a pub or RSL club. In Avalon’s case, transmissions were spurred on by a second day of multiple transmissions at a bowling club.

The source of the Avalon cluster was still not known, while the Crossroads source was detected relatively quickly as a Melbourne man who had arrived in Sydney just before the NSW-Victoria border closed.

But the relatively small scale of the outbreaks in the global context means few conclusions can be definitively drawn as to why the Avalon and Berala clusters were brought under control in a fraction of the time it took for the Crossroads cluster to subside, Professor Kaldor said.

“The degree you can really draw comprehensive epidemiological conclusions about what distinguishes this outbreak from another is quite limited. It’s an analysis worth doing but it is unlikely to provide definitive conclusions,” he said.

“We are limited in our ability to understand the differences, in a good way, by our success. For researchers, that makes it harder to understand these things but, from a public perspective, it’s great news.

“There is no question that contact tracing methodology has been perfected over time. Decisions about who should be isolated and who should be followed up have been improved and tightened.

“The only actual lockdown in NSW was the northern beaches in December and it was reported that the geography made the area more amenable to lockdown than other parts of Sydney. But all of this is speculative.”

Low testing numbers were of concern to health authorities yesterday. There were 8811 tests reported in the 24 hours to 8pm on Saturday night, down from the previous day’s total of 10,504.

“With restrictions on gatherings having eased across Greater Sydney, it is even more important that people keep up their guard and remain on the lookout for any signs or symptoms which could indicate COVID-19,” the health ministry said in a statement.

Loading

“While NSW has now seen 14 days without a known locally acquired case of COVID-19, the virus may still be circulating in the community among people with mild or no symptoms. We have previously seen successive days of no local cases, only to see cases re-emerge.”

Sewage surveillance detected fragments of the virus that causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) in the network at Warriewood, Liverpool and Malabar.

The detections may be explained by recently confirmed cases in these areas, but NSW Health is urging everyone living and working in these catchments to monitor for symptoms and get tested and isolate immediately if they appear.

There were three new cases detected in people returning from overseas in quarantine reported on Sunday, bringing the total number of COVID cases in NSW since the beginning of the pandemic to 4915.

NSW Health is treating 49 COVID-19 cases, none of whom are in intensive care. Most cases

(96 per cent) are being treated in non-acute, out-of-hospital care, including returned travellers in the Special Health Accommodation.

Kate Aubusson is Health Editor of The Sydney Morning Herald.

Most Viewed in National

Loading