Loading

It is also not fair to Porter, clearly devastated by the allegations and the public debate over them, to leave them hovering as they are.

Contrary to what the Prime Minister said earlier this week, this is not solely a matter for the police. It is also a matter for the Prime Minister and his cabinet colleagues – to respond by initiating a thorough, impartial and – importantly – confidential investigation.

NSW Police understandably concluded on Tuesday that no prosecution could be brought. The alleged assault happened 33 years ago, when Porter says he was 17. The complainant was then 16. She, however, is dead, having taken her own life last year.

While it is technically possible to bring a criminal prosecution where a complainant is dead, these factors weigh heavily against the chances of a successful prosecution. And prosecutorial guidelines require police and prosecutors to take that prospect into account when deciding whether to pursue charges.

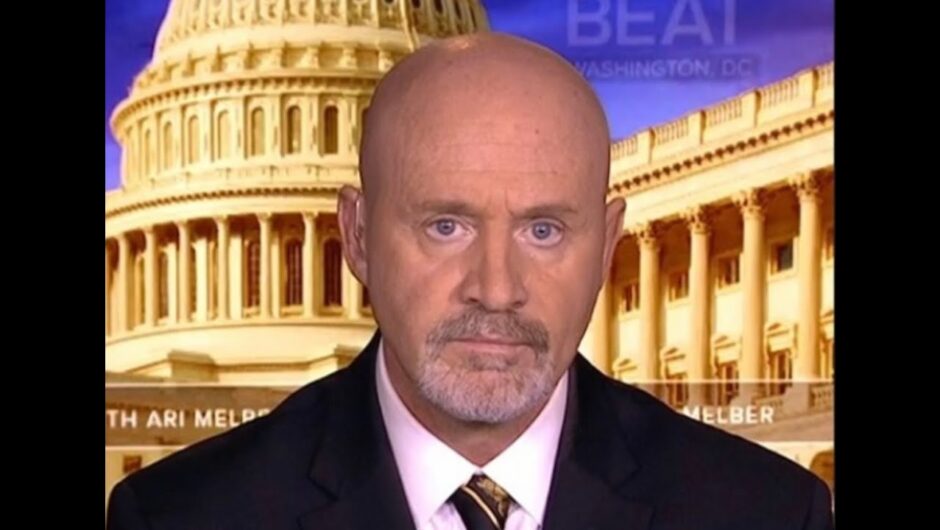

Attorney General Christian Porter’s press conference in Perth on Wednesday. Credit:Trevor Collens

This does not mean, however, that the police necessarily made any affirmative finding that the complainant or her allegations lacked credibility. Porter told the media he had no idea as to why why she would make these claims against him.

The nation is therefore left with this serious allegation of criminality against its highest law officer, with only his heartfelt denial – and a decision by the police not to pursue the matter – as the answer to that allegation.

This leaves us with a very serious problem. How can we expect the public to have trust and confidence in our legal or political system while these allegations remain in circulation and untested?

We cannot. We need the Prime Minister properly to test these allegations by initiating the kind of investigation conducted by Vivienne Thom at the request of the High Court, when faced with credible allegations of sexual harassment against Justice Dyson Heydon.

There has been an understandable desire to ensure fairness to Porter, and to avoid subjecting him to a form of trial by media – a public trial, with no rules of evidence, and little opportunity for acquittal. Anyone facing criminal charges would be entitled to the presumption of innocence and a fair trial.

But this does not mean that there should be no testing of the allegations – only that they should occur in a proper confidential inquiry governed by legal norms and standards.

Loading

While it may be harder to ensure fairness to the Attorney-General, now that his name is public, there are numerous lawyers and former judges in Australia with the independence of mind and character to test these allegations fairly and thoroughly, even under the glare of public scrutiny.

Testing of this kind would need to involve Porter being provided with the specifics of the allegations against him, and the opportunity to test the credibility of those allegations, including by asking questions about the complainant’s mental state, any history of unreliability or motive to lie on her part.

To his credit, Porter opened himself up to some of this testing in his press conference on Wednesday. But this kind of questioning is not the same as questioning under oath, with the benefit of examining all possible sources of supporting or corroborative evidence.

This investigation would not be for the purpose of any criminal prosecution, but to decide whether, when the Attorney-General returns from leave, he should be judged fit to hold the highest form of public office. Maybe he his. He certainly mounted a powerful public defence of his position on Wednesday.

But we owe it to both the system, and ultimately the Attorney-General himself, to test that question according to proper legal processes and standards.

Rosalind Dixon is a professor of law & director of the Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law at UNSW Sydney.

Rosalind Dixon is a professor of law at UNSW Sydney and Director of the Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading