news, latest-news, Great conjunction, astronomy, Jupiter, Saturn

Canberra’s skywatchers should plan an early evening walk on Monday to observe a very rare celestial event in the western skies just after the sun sets over the Brindabella mountain range. Combined on Monday with the summer solstice – the longest day in the southern hemisphere – will be the “great conjunction” when Jupiter and Saturn become two of the brightest objects in the night sky. These planetary conjunctions occur every 20 years but these two planets haven’t been so close and so visible since March 4, 1226. The two planets will almost become one singular star in the western sky but in reality, they will be 640 million kilometres apart. The best viewing time is about 9pm, or 45 minutes after the 8.18pm sunset as the two gas giants, one with its extraordinary rings and the other the largest planet in our solar system, cross paths and begin to separate through the rest of the month. While observable to the naked eye, Monday night’s event is best observed through binoculars or a telescope. It is called a “great” conjunction because to ancient skywatchers, Jupiter and Saturn were the two slowest moving planets in the sky. Jupiter takes 12 years to take a full lap of the sun, while Saturn takes 29.5 years. The great conjunction’s importance in history as the so-called Star of Bethlehem was a theory proposed back in the 17th century by German astronomer Johannes Kepler – which had NASA’s orbiting telescope bearing his name – and has re-emerged again, this time fuelled by social media. However, most astronomers have dismissed this theory as more theological in its basis than historical. The Kepler telescope was launched by NASA in March 2009 and put into space the largest digital telescope at the time. Kepler took the first survey of planets in our galaxy and became the first NASA mission to detect Earth-sized planets in the habitable zones of their stars. Nine years later and 2600 planet discoveries later, the Kepler spacecraft ran out of fuel but is still orbiting the earth.

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/fdcx/doc7dpxai2yx473ty6xbxl.jpg/r0_136_1041_724_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

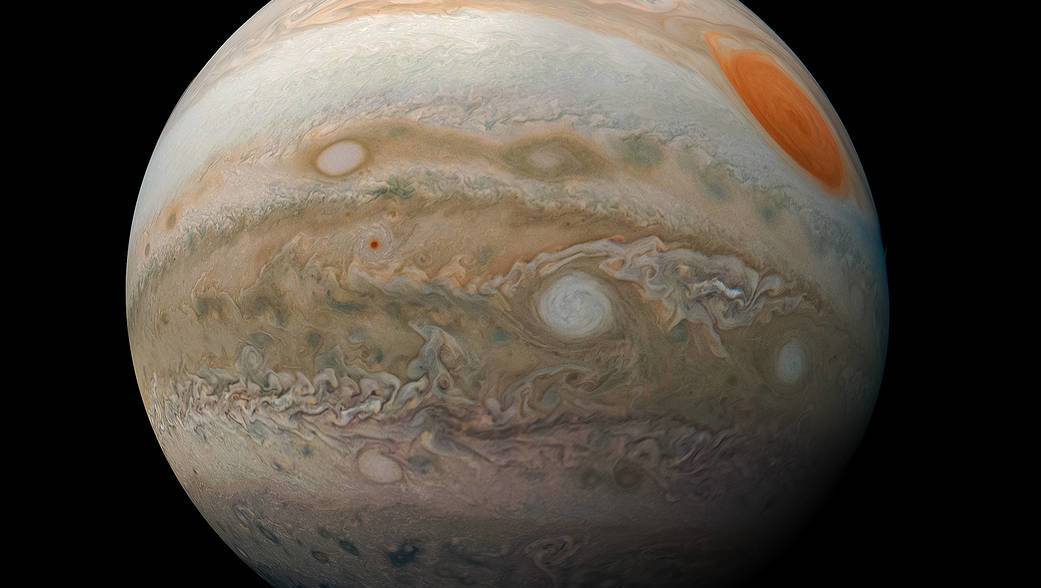

Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, will pass by Saturn, in the western sky just after sunset tonight. Picture: NASA

Canberra’s skywatchers should plan an early evening walk on Monday to observe a very rare celestial event in the western skies just after the sun sets over the Brindabella mountain range.

Combined on Monday with the summer solstice – the longest day in the southern hemisphere – will be the “great conjunction” when Jupiter and Saturn become two of the brightest objects in the night sky.

These planetary conjunctions occur every 20 years but these two planets haven’t been so close and so visible since March 4, 1226.

The two planets will almost become one singular star in the western sky but in reality, they will be 640 million kilometres apart.

Saturn will be one of the brightest objects in the night sky on Monday during the great conjunction. Picture: NASA

The best viewing time is about 9pm, or 45 minutes after the 8.18pm sunset as the two gas giants, one with its extraordinary rings and the other the largest planet in our solar system, cross paths and begin to separate through the rest of the month.

While observable to the naked eye, Monday night’s event is best observed through binoculars or a telescope.

It is called a “great” conjunction because to ancient skywatchers, Jupiter and Saturn were the two slowest moving planets in the sky. Jupiter takes 12 years to take a full lap of the sun, while Saturn takes 29.5 years.

The great conjunction’s importance in history as the so-called Star of Bethlehem was a theory proposed back in the 17th century by German astronomer Johannes Kepler – which had NASA’s orbiting telescope bearing his name – and has re-emerged again, this time fuelled by social media.

However, most astronomers have dismissed this theory as more theological in its basis than historical.

The Kepler telescope was launched by NASA in March 2009 and put into space the largest digital telescope at the time. Kepler took the first survey of planets in our galaxy and became the first NASA mission to detect Earth-sized planets in the habitable zones of their stars.

Nine years later and 2600 planet discoveries later, the Kepler spacecraft ran out of fuel but is still orbiting the earth.