A father-of-seven who has lived in Australia for more than 40 years believing he was an Australian citizen has had his deportation order overturned in a landmark Federal Court ruling.

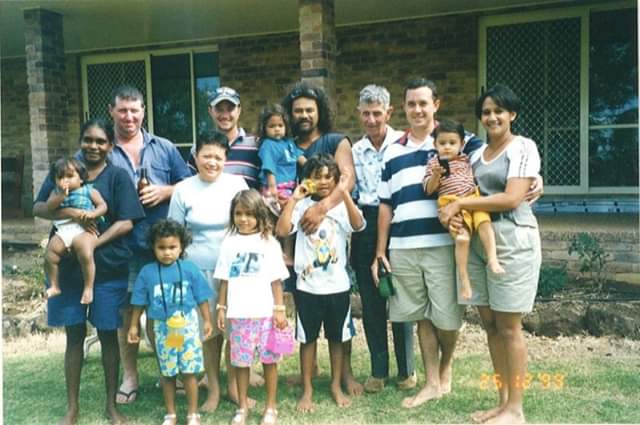

Edward McHugh, 52, was born in the Cook Islands and adopted by a Queensland family in the 1970s when he was six years old. He went on to father seven Aboriginal children and was granted an Australian passport, leading him to believe he was a citizen.

But after being convicted in 2018 of aggravated assault and making a threat to kill, he was shocked to discover he was facing deportation to New Zealand after serving a nine-month prison sentence under section 501 of the Immigration Act, as revealed by SBS News in 2018.

He spent more than two and a half years in immigration detention centres in Perth and Melbourne until a landmark appeal ruling by the full bench of the Federal Court last Friday granted him his freedom.

“I was jumping out of my boots,” Mr McHugh told SBS News from Melbourne of the moment he heard he would be released.

“I’m feeling free and I feel like justice has been served … I always knew who I am.”

The ruling relied on the centuries-old writ of habeas corpus which is used to rule on whether the detention of a person by the state is unlawful.

It is only the second time in Australia’s recent history that habeas corpus has been used to free someone from immigration detention.

In handing down the ruling, Chief Justice James Allsop reversed a previous decision on whether the Federal Court had the jurisdiction to make orders to release people from detention, and therefore found that Mr McHugh’s detention was unlawful, ordering his immediate release.

A key ruling as to the lawfulness of the detention was that the onus was on the government to provide sufficient evidence that Mr McHugh – who spent long periods living within Aboriginal communities, where he held a ceremonial role – was not an Indigenous Australian, and therefore able to be deemed an unlawful alien

“[Mr McHugh] is recognised by the Aboriginal community in which he has lived for many years as Aboriginal and part of that community, but who is (at least presently) unable to bring positive proof of his biological Aboriginal descent,” Chief Justice Allsop wrote in his judgement.

“The task of the Commonwealth … is straightforward, at least in expression, and a simple reflex of Mr McHugh’s elementary and fundamentally important right to his liberty free from unlawful Executive detention: prove the lawfulness of his detention.”

The judgement followed a protracted legal battle to have Mr McHugh’s right to remain in the country reassessed.

In June, the Federal Court ordered acting Immigration Minister Alan Tudge to reconsider the cancellation of Mr McHugh’s visa after earlier refusals.

The government had argued Mr McHugh had never received Australian citizenship as his adoption to Australian parents did not mean he was a citizen as it took place before the laws were changed to allow automatic citizenship in 1984. He had also never applied for citizenship by descent, they said.

His Australian passport was revoked following the conviction but no explanation has been provided as to why his Queensland birth certificate and adoption papers allowed him to be granted one in the first place.

According to the Department of Home Affairs, Mr McHugh was in Australia on an Absorbed Person Visa, a visa category that does not require the holder to be aware of their visa status.

This was revoked following his prison sentence in February 2018.

The court did not dispute the department’s position that Mr McHugh did not hold citizenship or a valid visa. All residents of the Cook Islands are automatically granted New Zealand citizenship.

Marleen Charan, founder of advocacy group Rights and Reform Inc., supported Mr McHugh through his legal challenge and told SBS News the ruling was “high time coming”.

“It took a long time for them to assess this application,” Ms Charan said.

“Although it took a long time, it is a result that we’ve been waiting for – and I guess, a lot of detainees were waiting for.”

A Department of Home Affairs spokesperson said they were aware of the Federal Court’s ruling and were considering the reasons for the court’s decision and the implications of the judgement.