news, federal-politics,

Ideological extremism now makes up about 40 per cent of ASIO’s counter-terrorism caseload, the spy agency’s boss has warned. In a speech highlighting the “threat environment” faced by Australia, Director-General of Security Mike Burgess said the extremists being tracked by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation weren’t simply “skinheads with swastika tattoos and jackboots roaming the back streets like extras from Romper Stomper”. “It’s no longer that obvious.” The COVID-19 pandemic and harsh government restrictions fuelled extremists’ beliefs about societal collapse and race war, Mr Burgess said. Extremists were more reactive to world events, like the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement and even last year’s presidential election in the United States. “As a consequence, we are seeing extremists seeking to acquire weapons for self-defence, as well as stockpiling ammunition and provisions,” Mr Burgess said. More time spent at home during the pandemic meant “more time in the echo chamber of the internet on the pathway to radicalisation,” he said of extremists across the spectrum. “They were able to access hate-filled manifestos and attack instructions, without some of the usual circuit breakers that contact with community provides.” In the past year, Mr Burgess has raised the alarm on the increasing threat of right-wing extremism in Australia, but on Wednesday he announced the agency would change its language to refer to religiously motivated violent extremism and ideologically motivated violent extremism. “Today’s ideological extremist is more likely to be motivated by a social or economic grievance than national socialism. More often than not, they are young, well-educated, articulate, and middle class – and not easily identified,” he said. The change in language reflects the changing face of threats to Australians, he said. “We are seeing a growing number of individuals and groups that don’t fit on the left-right spectrum at all; instead, they’re motivated by a fear of societal collapse or a specific social or economic grievance or conspiracy,” Mr Burgess said. “For example, the violent misogynists who adhere to the involuntary celibate or ‘incel’ ideology fit into this category.” READ MORE: Using the umbrella terms didn’t mean the security agency would not refer to more specific types of extremism when appropriate, Mr Burgess said. The average age of people investigated by ASIO is 25, they are overwhelmingly male, and children as young as 15 and 16 were also being radicalised, he said. The ideological extremist threat wasn’t contained in any one state or territory, and was more widely dispersed across the country, including in rural and regional areas. “ASIO anticipates that the threat from this form of extremism will not diminish anytime soon – and may well grow,” he said. The overall terrorist threat in Australia remains “probable,” the Director-General said, pointing to two religiously motivated terrorist attacks in Australia late last year, and two “disruptions” where individuals have been charged with planning a terrorist attack. “An ideologically motivated terrorist attack in Australia remains plausible, most likely by a lone actor or small cell rather than a recognised group, and using a knife or a vehicle rather than sophisticated weapons,” Mr Burgess said. The Director-General made it clear the spy agency didn’t target religious belief, political views or non-violent protests, but violence itself. Our journalists work hard to provide local, up-to-date news to the community. This is how you can continue to access our trusted content:

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/rJkJNFPcdBkDQKqtkgHSjA/51108ef9-3c8d-4d81-99e7-c0532a30612d.jpg/r0_73_5500_3181_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

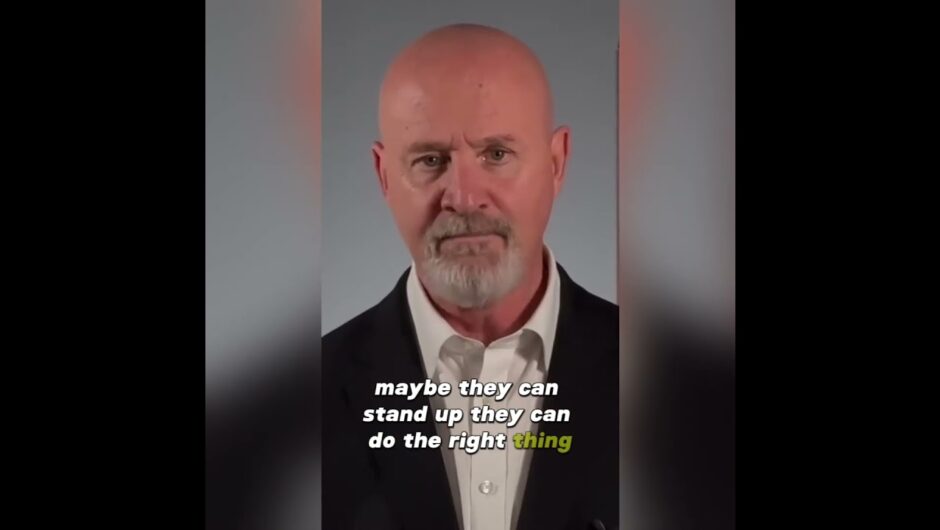

Ideological extremism now makes up about 40 per cent of ASIO’s counter-terrorism caseload, the spy agency’s boss has warned.

In a speech highlighting the “threat environment” faced by Australia, Director-General of Security Mike Burgess said the extremists being tracked by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation weren’t simply “skinheads with swastika tattoos and jackboots roaming the back streets like extras from Romper Stomper”.

“It’s no longer that obvious.”

The COVID-19 pandemic and harsh government restrictions fuelled extremists’ beliefs about societal collapse and race war, Mr Burgess said. Extremists were more reactive to world events, like the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement and even last year’s presidential election in the United States.

“As a consequence, we are seeing extremists seeking to acquire weapons for self-defence, as well as stockpiling ammunition and provisions,” Mr Burgess said.

More time spent at home during the pandemic meant “more time in the echo chamber of the internet on the pathway to radicalisation,” he said of extremists across the spectrum.

“They were able to access hate-filled manifestos and attack instructions, without some of the usual circuit breakers that contact with community provides.”

In the past year, Mr Burgess has raised the alarm on the increasing threat of right-wing extremism in Australia, but on Wednesday he announced the agency would change its language to refer to religiously motivated violent extremism and ideologically motivated violent extremism.

“Today’s ideological extremist is more likely to be motivated by a social or economic grievance than national socialism. More often than not, they are young, well-educated, articulate, and middle class – and not easily identified,” he said.

The change in language reflects the changing face of threats to Australians, he said.

“We are seeing a growing number of individuals and groups that don’t fit on the left-right spectrum at all; instead, they’re motivated by a fear of societal collapse or a specific social or economic grievance or conspiracy,” Mr Burgess said.

“For example, the violent misogynists who adhere to the involuntary celibate or ‘incel’ ideology fit into this category.”

Using the umbrella terms didn’t mean the security agency would not refer to more specific types of extremism when appropriate, Mr Burgess said.

The average age of people investigated by ASIO is 25, they are overwhelmingly male, and children as young as 15 and 16 were also being radicalised, he said.

The ideological extremist threat wasn’t contained in any one state or territory, and was more widely dispersed across the country, including in rural and regional areas.

“ASIO anticipates that the threat from this form of extremism will not diminish anytime soon – and may well grow,” he said.

The overall terrorist threat in Australia remains “probable,” the Director-General said, pointing to two religiously motivated terrorist attacks in Australia late last year, and two “disruptions” where individuals have been charged with planning a terrorist attack.

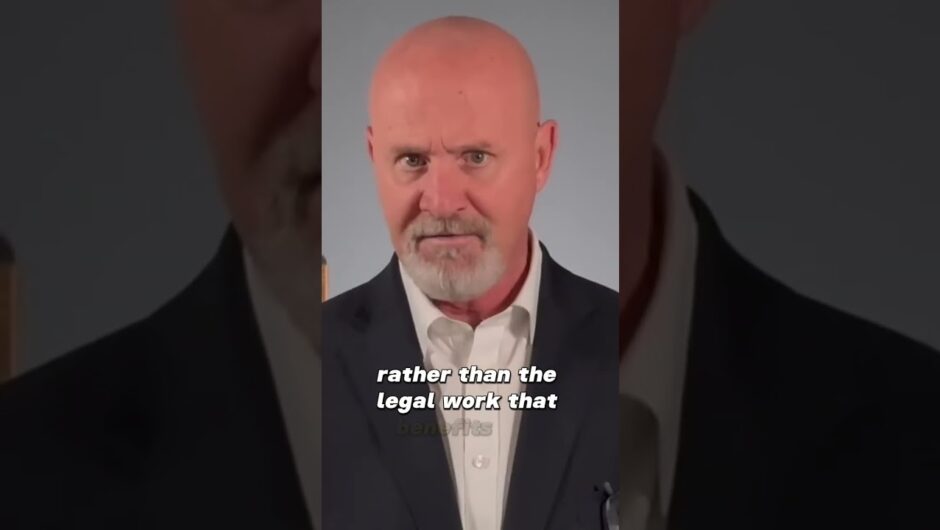

“An ideologically motivated terrorist attack in Australia remains plausible, most likely by a lone actor or small cell rather than a recognised group, and using a knife or a vehicle rather than sophisticated weapons,” Mr Burgess said.

The Director-General made it clear the spy agency didn’t target religious belief, political views or non-violent protests, but violence itself.

Our journalists work hard to provide local, up-to-date news to the community. This is how you can continue to access our trusted content: