When Sean Abbott bowled his first spell at Manuka Oval on Wednesday afternoon, he broke India’s opening stand after five balls. Three overs, 1 for 14.

When Abbott bowled his final spell in India’s innings, Hardik Pandya and Ravindra Jadeja went to town. Three overs, none for 49.

Those two ends of that innings seemed a very long way apart.

When Abbott played his first One-Day International for Australia, it was in the Emirati city of Sharjah in October, 2014.

When he played his second one-dayer, it was in Canberra on Wednesday of this week in the final month of a long 2020.

Those two parts of that career seem a very long way apart.

During the six intervening years he made a few white-ball squads, watched from the bench, got injured at bad times, and played three T20s for Australia.

He also put together one of the most consistent resumes in domestic cricket, both in the Sheffield Shield and in the Big Bash.

This season, a three-match Shield streak yielding 14 wickets and a breakthrough century saw Abbott break through into a Test squad for the first time, as well as get another run in the white-ball squad.

Finding resilience

By chance, when Australia’s one-day series against India started last Friday, it was the sixth anniversary of the day that Phillip Hughes died, injured by the ball while batting in a Shield game at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

Abbott was the bowler for New South Wales that day, and this time of year must always be difficult for him.

Gearing up for an Australian series this year might equally have been a welcome distraction or a stronger reminder.

He was never likely to be playing in the first ODI, with Australia’s top three fast bowlers available, but even if they hadn’t been, team management might have thought twice about picking him.

Being out playing on the same SCG at 4:08pm, the time of day when the crowd paid respects to Hughes by reference to his 408 Test cap number, would have been a big ask.

Loading

Instead, Abbott got his opportunity a few days later.

Resilience has been something he has had to find in himself.

He got back to playing soon after the accident, and while he has described moments where his enthusiasm has waned, he has in the main stuck to his task of playing and improving.

Last season he helped New South Wales win the Shield and the Sydney Sixers win the Big Bash.

This season, his performances helped his state draw with a strong Western Australia side, before he was the not-out batsman in the run chase to seal a one-wicket win over Queensland, before he helped pull off a remarkable recovery to beat Tasmania after being bowled out for 64 on the first day.

After a lot of years of being there and thereabouts, described as a player for the future or a player of potential, Abbott was making the statement that the future was now, and the national selectors were inclined to listen.

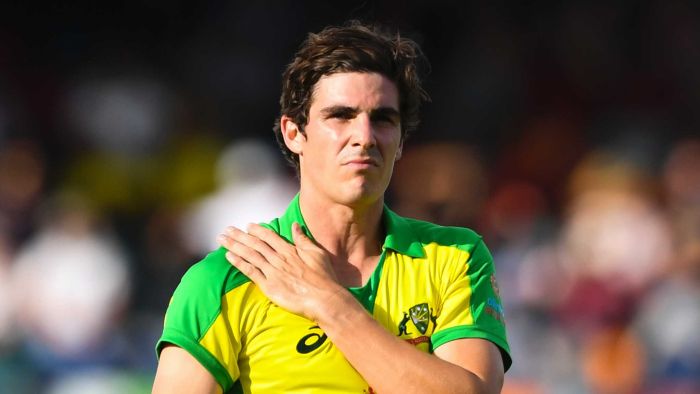

So here he was, back in Australian green and gold in the 50-over format, ending that long, long wait.

India’s Shikhar Dhawan is a vastly experienced opener, an aggressor against pace who has made 17 centuries in one-day cricket.

He likes to walk at bowlers and slap the ball over the off side. When he tried it, Abbott foxed him with bounce to make him splice a catch to cover.

Abbott got flustered. But he must understand game’s ups and downs

Following his early success, Abbott came back for three short bursts through the middle of the innings of one or two overs apiece, and returned tidy figures. It was right at the back end of the innings when the wheels started coming off.

Pandya is a striker of tremendous strength, doing things like backing away to play cut shots over cover for six.

Jadeja’s strength is speed on his feet, and he used that to shift around his crease and create the line he wanted.

Correctly assessing that Abbott’s boundaries were unprotected behind square on both sides of the wicket, and thus that the line would be very wide of off stump, Jadeja found ways to divert those deliveries fine enough to reach the rope.

In the heat of the moment, Abbott got flustered.

He slipped in some full tosses, and he went too often to his short ball, which Jadeja punished.

What had been seven overs, 1 for 37, ended up being 10 overs, 1 for 84. It would have stung.

Much later in the night, too, Abbott came in with the bat when Australia’s run chase of 303 was slipping away. They needed 35 with five overs left and three wickets in hand.

He had the chance to steal back the match for Australia, but gloved a hook shot and was out for four. The romantic ending was not to be.

And through those years since, he must understand better than most the nature of the game’s ups and downs.

Abbott has worked harder than that. To get back here, to even be in a position to get back here. Long summers of state cricket, late nights of Big Bash cricket, wicket after wicket, match after match.

He has worked harder than a couple of bad overs on a December afternoon. The next moment will come soon, and the next. That’s how it works.