news, latest-news, bushfires, Black Summer bushfires, NSW South Coast, climate change

On Braidwood Road in the bush community of Tianjara, about 50 kilometres south-west of Nowra, two plots of land tell different stories. A brick house stands on one, its unfinished roof a skeleton of timber framing. On another, stonework remains hint at the home that once stood there. Both plots were in the path of a bushfire that turned the air black, then white, and had residents fleeing for safety as it approached. The Tianjara fire destroyed the houses on each block, as it raced inland on December 21, 2019 after starting two days earlier. One of the property owners, Lindsay Lavis, is rebuilding his house. His neighbour, Andrew Phillips, has moved away permanently. Mr Phillips packed as many of his belongings into his truck as he could fit when evacuating his home the night before the fire came. The vehicle carried his goat, chickens, rooster, cat, computer, clothes, and any items that would help if he was stranded on the way out. He did two things before leaving Tianjara to join his wife in seeking safety at the Shoalhaven village of Berry. First, he walked through their house to say goodbye. “I thought it was very unlikely it was going to survive. Certainly driving out through the ash, and through the smoke with the cat on the dashboard, it was quite a strange situation,” Mr Phillips says. He was initially going to stay and defend the house. When volunteers from the Tomerong Rural Fire Service brigade arrived from the NSW South Coast expecting the fire to hit that evening, he was confident about saving his home. The fire didn’t arrive that night, and brigade members returned to the coast, expecting to defend larger communities in catastrophic conditions on December 21. Advised by firefighters to leave while he could, Mr Phillips packed and left at about midnight. “The thing I remember so much was the smell, the horrible, horrible stink of the ash falling down, the absolute stench of the fire as it was approaching. I don’t think I will ever forget that,” he says. At first, Lindsay Lavis stayed the next day to defend his property. His wife had already evacuated the home. A towering cloud – called a pyrocumulonimbus – loomed above as the approaching fire generated its own weather. Mr Lavis reckoned it 20,000 feet high, rolling through with lightning and thunder. When conditions worsened, firefighters defending his property that afternoon told him to leave for safety. “It was coming that quick, it was moving too fast,” Mr Lavis says. “I got a bit anxious when I saw them putting on their flame proof masks and I thought, ‘this is going to get serious’.” He sheltered at a pub in the nearby village of Nerriga. The fire sounded like a freight train on its approach. “It’s a sound you will never ever forget, once you’ve heard it,” Mr Lavis says. He returned home next day to a mass of warped metal, which had buckled from the furious heat of the Tianjara fire as it swept through. Mr Phillips, unable to get past roadblocks, couldn’t see his property for three weeks. The remains of his house were a smoky heap of collapsed corrugated iron. Red plastic on the rear lights of his wife’s car had dripped down the boot like paint. Mr Lavis lost all his possessions in the fire but emerged from the disaster grateful it wasn’t worse. “My wife was safe and no one got hurt and that’s all that really matters,” he says. “Possessions don’t mean much to me. It’s family, that’s all that matters.” The property now has an underground mine bunker that can keep two people alive for 29 hours. It’s air conditioned and blast proof. Mr Lavis plans to shelter in it, if another bushfire comes. “If we ever get another fire, we’ll be staying,” he says. While Tianjara was vulnerable to the bushfires of last summer, its isolation made it a safe haven in the next crisis of 2020. During the pandemic, Mr Lavis had another reason to stay there. “It’s really important now we’ve got coronavirus. We’re miles from that,” he says. “It’s nice, quiet and peaceful. We’ve got lyrebirds every morning around us. It’s good.” Mr Lavis got through a cold winter living in his shed while his new house was built. He doesn’t consider himself unfortunate, despite the Tianjara fire. “We’re getting along alright, we’ll be right once the house is finished, it’ll be all good,” he says. “I just hope it doesn’t happen again.” Before evacuating his home on December 20, 2019, Andrew Phillips did one other final thing. He packed a Ross Garnaut book about the potential for Australia to be an economic superpower in the future post-carbon world. It had given him hope after his work researching health and the environment that year had made him distressed about climate change. “You can cope with losing your house, but losing hope is not something I could cope with,” Mr Phillips says. “The whole deal with climate change is those particular events become more and more likely, and the fact we are doing so little nationally to actually address the issue is pretty distressing, and you can lose hope.” Mr Phillips, having followed climate science for decades, says the nation will need to increase its resilience to the effects of climate change. It will also need to reduce carbon emissions. “If you do only one of those things, you’re not really going to achieve very much.” At Tianjara, properties border on large tracts of bush, far away from the busyness of coastal towns. Mr Phillips says he loves to be there. “It’s got so many things going for it. The view’s incredible. It’s just a wonderful place to be, and the animals and plants up there and the forest have been fantastic,” he says. On a practical level, he’s glad he left his property before the fire and avoided the trauma of seeing it burn. “I’m not sure I would’ve been able to save the place, so the thought of watching the place burn to the ground, that would have been worse than actually going back up and finding it burnt out.” After the fire, a slow path to recovery awaited. “One of the biggest traumas we had was proving to people we actually lived there. We didn’t have a street address, there was no mail service, there were no services at all, so we didn’t actually have any paperwork that actually proved that we lived there,” Mr Phillips says. “Everything we might have used to prove it had been burnt so we had to trawl through our emails and whatever photographs we could get together to prove to charities and government agencies that we actually lived there.” The bush surrounding Mr Phillips’ former home is slowly recovering. In some areas, the damage has been lasting. It has a visceral impact on the former resident. “To go up there, I’ve got to drive through all that burnt-out country and it’s starting to affect me,” he says. “I actually shudder as I drive through it, it’s just the sheer devastation and there are so many trees that aren’t coming back.” Mr Phillips is still cleaning up his Tianjara property. He and his wife have decided not to move back, and will eventually sell. “The trauma was pretty substantial and so we’ve bought elsewhere,” he says. READ MORE: The decision was a wrench on him. He’s still grieving the home he built there. Mr Phillips had quarried the stone, milled the timber, and built his beloved home surrounded by bush before moving in during 2014. “This was the place that we were going to spend the next 20 or 30 years of our life.” Mr Phillips is moving on, making a new home in Berry with his wife, where they’re closer to family and services. “It is further away from the forest, which after the ash and the smell and the trauma of what we went through, I think it’s probably a sensible idea.” He still misses the community at Tianjara. “You’ve just got to let it go. If you dwelt on it, you could beat yourself up terribly and be quite badly affected,” he says, speaking in Berry. “I know I’m adaptable. I’ve had quite a few changes in the past. It’s hard coming to a new place, but then after six months, it’s like ‘well OK, this is home, this is the new place’. “That’s becoming the case here.”

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/36i7SKuzkApKRqnK2hWiW9n/fb7a0229-27c8-4415-a728-a529123f3591.jpg/r14_503_4895_3261_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

On Braidwood Road in the bush community of Tianjara,about 50 kilometres south-west of Nowra, two plots of land tell different stories.

A brick house stands on one, its unfinished roof a skeleton of timber framing.

On another, stonework remains hint at the home that once stood there.

Both plots were in the path of a bushfire that turned the air black, then white, and had residents fleeing for safety as it approached.

The Tianjara fire destroyed the houses on each block, as it raced inland on December 21, 2019 after starting two days earlier.

One of the property owners, Lindsay Lavis, is rebuilding his house. His neighbour, Andrew Phillips, has moved away permanently.

Mr Phillips packed as many of his belongings into his truck as he could fit when evacuating his home the night before the fire came. The vehicle carried his goat, chickens, rooster, cat, computer, clothes, and any items that would help if he was stranded on the way out.

He did two things before leaving Tianjara to join his wife in seeking safety at the Shoalhaven village of Berry. First, he walked through their house to say goodbye.

“I thought it was very unlikely it was going to survive. Certainly driving out through the ash, and through the smoke with the cat on the dashboard, it was quite a strange situation,” Mr Phillips says.

He was initially going to stay and defend the house. When volunteers from the Tomerong Rural Fire Service brigade arrived from the NSW South Coast expecting the fire to hit that evening, he was confident about saving his home.

I actually shudder as I drive through it, it’s just the sheer devastation and there are so many trees that aren’t coming back.

Andrew Phillips

The fire didn’t arrive that night, and brigade members returned to the coast, expecting to defend larger communities in catastrophic conditions on December 21. Advised by firefighters to leave while he could, Mr Phillips packed and left at about midnight.

“The thing I remember so much was the smell, the horrible, horrible stink of the ash falling down, the absolute stench of the fire as it was approaching. I don’t think I will ever forget that,” he says.

At first, Lindsay Lavis stayed the next day to defend his property. His wife had already evacuated the home.

A towering cloud – called a pyrocumulonimbus – loomed above as the approaching fire generated its own weather. Mr Lavis reckoned it 20,000 feet high, rolling through with lightning and thunder.

When conditions worsened, firefighters defending his property that afternoon told him to leave for safety.

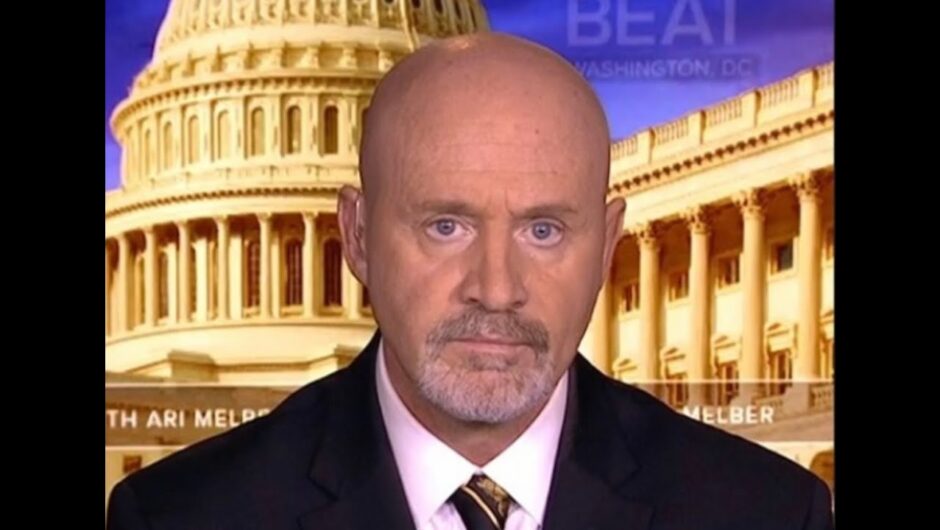

Lindsay Lavis on December 22, 2019, the day after the Tianjara fire destroyed his home. Picture: Dion Georgopoulos

“It was coming that quick, it was moving too fast,” Mr Lavis says.

“I got a bit anxious when I saw them putting on their flame proof masks and I thought, ‘this is going to get serious’.”

He sheltered at a pub in the nearby village of Nerriga. The fire sounded like a freight train on its approach.

“It’s a sound you will never ever forget, once you’ve heard it,” Mr Lavis says.

He returned home next day to a mass of warped metal, which had buckled from the furious heat of the Tianjara fire as it swept through.

Mr Phillips, unable to get past roadblocks, couldn’t see his property for three weeks. The remains of his house were a smoky heap of collapsed corrugated iron. Red plastic on the rear lights of his wife’s car had dripped down the boot like paint.

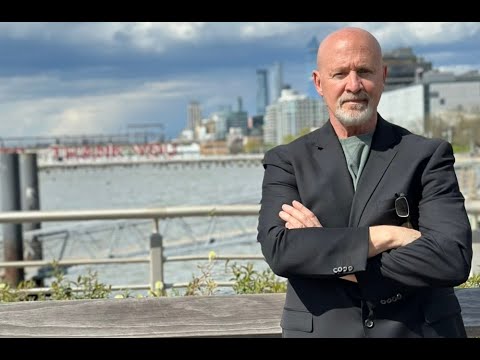

Fire swept through Andrew Phillips’s property on December 21, 2019 and destroyed his home. Picture: Dion Georgopoulos

Mr Lavis lost all his possessions in the fire but emerged from the disaster grateful it wasn’t worse.

“My wife was safe and no one got hurt and that’s all that really matters,” he says.

“Possessions don’t mean much to me. It’s family, that’s all that matters.”

The property now has an underground mine bunker that can keep two people alive for 29 hours. It’s air conditioned and blast proof. Mr Lavis plans to shelter in it, if another bushfire comes.

“If we ever get another fire, we’ll be staying,” he says.

While Tianjara was vulnerable to the bushfires of last summer, its isolation made it a safe haven in the next crisis of 2020. During the pandemic, Mr Lavis had another reason to stay there.

“It’s really important now we’ve got coronavirus. We’re miles from that,” he says.

“It’s nice, quiet and peaceful. We’ve got lyrebirds every morning around us. It’s good.”

Mr Lavis got through a cold winter living in his shed while his new house was built. He doesn’t consider himself unfortunate, despite the Tianjara fire.

“We’re getting along alright, we’ll be right once the house is finished, it’ll be all good,” he says.

“I just hope it doesn’t happen again.”

The wrench of a lost home

Before evacuating his home on December 20, 2019, Andrew Phillips did one other final thing.

He packed a Ross Garnaut book about the potential for Australia to be an economic superpower in the future post-carbon world. It had given him hope after his work researching health and the environment that year had made him distressed about climate change.

“You can cope with losing your house, but losing hope is not something I could cope with,” Mr Phillips says.

“The whole deal with climate change is those particular events become more and more likely, and the fact we are doing so little nationally to actually address the issue is pretty distressing, and you can lose hope.”

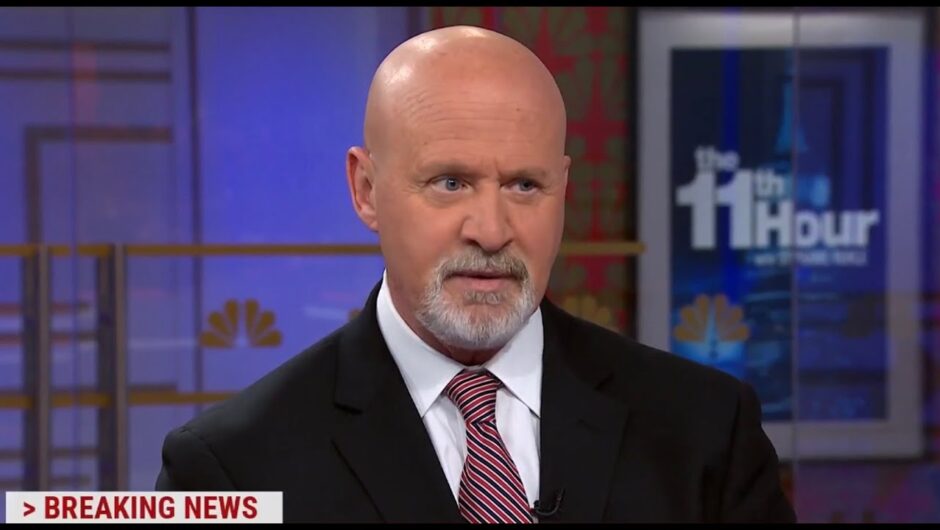

Andrew Phillips will make a new home elsewhere after bushfire destroyed his house in Tianjara. Picture: Elesa Kurtz

Mr Phillips, having followed climate science for decades,says the nation will need to increase its resilience to the effects of climate change. It will also need to reduce carbon emissions.

“If you do only one of those things, you’re not really going to achieve very much.”

At Tianjara, properties border on large tracts of bush, far away from the busyness of coastal towns. Mr Phillips says he loves to be there.

“It’s got so many things going for it. The view’s incredible. It’s just a wonderful place to be, and the animals and plants up there and the forest have been fantastic,” he says.

On a practical level, he’s glad he left his property before the fire and avoided the trauma of seeing it burn.

“I’m not sure I would’ve been able to save the place, so the thought of watching the place burn to the ground, that would have been worse than actually going back up and finding it burnt out.”

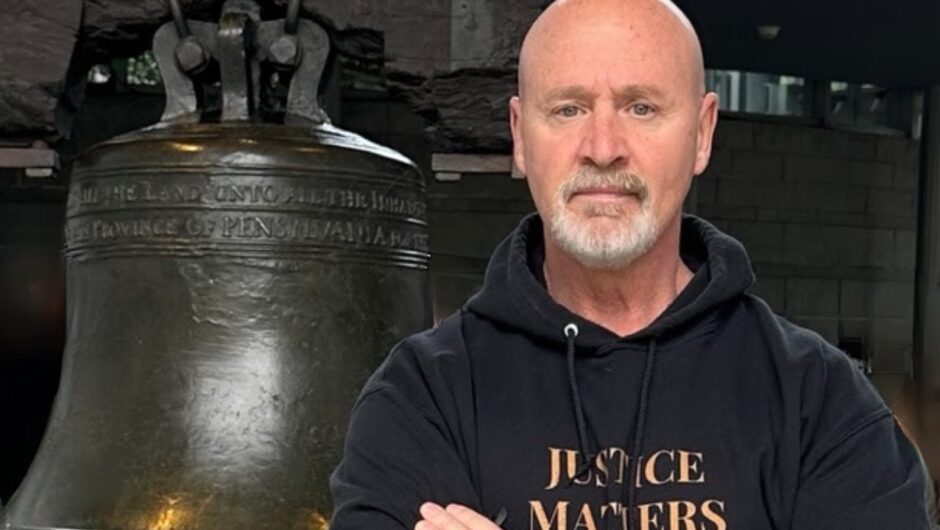

Andrew Phillips’ house on December 22, 2019. Fire reduced it to a heap of smouldering ruins. Picture: Dion Georgopoulos

After the fire, a slow path to recovery awaited.

“One of the biggest traumas we had was proving to people we actually lived there. We didn’t have a street address, there was no mail service, there were no services at all, so we didn’t actually have any paperwork that actually proved that we lived there,” Mr Phillips says.

“Everything we might have used to prove it had been burnt so we had to trawl through our emails and whatever photographs we could get together to prove to charities and government agencies that we actually lived there.”

The bush surrounding Mr Phillips’ former home is slowly recovering. In some areas, the damage has been lasting. It has a visceral impact on the former resident.

“To go up there, I’ve got to drive through all that burnt-out country and it’s starting to affect me,” he says.

“I actually shudder as I drive through it, it’s just the sheer devastation and there are so many trees that aren’t coming back.”

Mr Phillips is still cleaning up his Tianjara property. He and his wife have decided not to move back, and will eventually sell.

“The trauma was pretty substantial and so we’ve bought elsewhere,” he says.

The decision was a wrench on him. He’s still grieving the home he built there.

Mr Phillips had quarried the stone, milled the timber, and built his beloved home surrounded by bush before moving in during 2014.

“This was the place that we were going to spend the next 20 or 30 years of our life.”

Mr Phillips is moving on, making a new home in Berry with his wife, where they’re closer to family and services.

“It is further away from the forest, which after the ash and the smell and the trauma of what we went through, I think it’s probably a sensible idea.”

He still misses the community at Tianjara.

“You’ve just got to let it go. If you dwelt on it, you could beat yourself up terribly and be quite badly affected,” he says, speaking in Berry.

“I know I’m adaptable. I’ve had quite a few changes in the past. It’s hard coming to a new place, but then after six months, it’s like ‘well OK, this is home, this is the new place’.

“That’s becoming the case here.”