news, latest-news,

One year after the vicious fire which devastated 80 per cent of the Namadgi National Park, greenery is creeping back to the Orroral Valley. But it is a deceptive greenery, according to Brett McNamara, the manager of the park on Canberra’s doorstep that seems like the lungs of the city. Look a little harder and you see signs of long-term damage. You can find them if you know where to look – and Mr McNamara knows where to look. He talks of his feeling of sadness. Creeks which should be flowing with water remain dry, silted with what he calls “slugs” of piled-up sludge. “To have come here before that fire, we would have found a babbling little creek, perhaps two metres deep. water flowing through this landscape,” Mr McNamara says. “But post-fire, with the amount of debris and the movement of sediment across this landscape, this has now formed a sediment slug,” he said. “This actually deprives native fish species of their habitat. We often think about the loss of mammals and insects but we don’t necessarily thinks about the impact on the aquatic environment.” And, most importantly, the source of Canberra’s water remains damaged and fragile. When the surveyor Charles Scrivener searched for a site for the nation’s as-yet unbuilt capital, he hit on this area because of the bogs which would soak up water and then release it. Last year’s fire burnt so much vegetation and sent so much debris into the bogs that their life-giving abilities are impaired. Wild animals trample them. “We have the pressure of feral deer coming onto these bogs. We also have the pressure of horses impacting on the bogs,” Mr McNamara said. “The impact of invasive species and fire has the potential of actually altering the functioning ecosystem of these bogs. “If the frequency of fire keeps impacting on the ecosystems, we actually start seeing the loss of water supply to the nation’s capital.” The fire was so devastating that the core of the park in the valley itself remains closed to the public. Tracks which were passable before the fire remain impassable today. Bridges which would have taken the weight of a truck are now too weak. It’s not so much the impact of one fire which worries Mr McNamara but the repeated impact of ever more intense and frequent fires. This heightened fire activity caused by global warming means the forest doesn’t have the chance to recover. In his 30 years at the park, its appearance has changed dramatically. The forest used to be thick but now trees don’t get time to grow before the next fire. “It’s a very different forest from what it was in the 1990s when I first started working here. “To witness the mountains burn once back in 2003 was confronting, but to have seen the mountains burn twice in one career tells you that there’s an ecological change that is occurring within these mountains.” One of the reasons last year’s fire was so bad was that it came after years of drought. Treading on tinder-dry grass was like stepping on corn flakes. The canopy, the tops of trees, was actually dead. The recovery currently underway in the park is “tainted with a sense of what does the future hold for us if we are to experience fire again and again with such intensity. This is where the question is unanswered. What these mountains will look like well into the future?” As he fears for the future, he remembers the past. The experience of a year ago is seared on his mind. He was in the park, fighting the fire, feeling its scorching danger. “There were moments when the fire was just coming down on top of us and we really did fear for our lives,” he says. The work of recovery continues, though with still no date for the re-opening of the core of the national park. The ACT’s Minister for Planning, Mick Gentleman said there was “excellent progress on our long-term bushfire recovery plan. We’re moving faster than we originally anticipated and I’m optimistic that more areas will be able to open sooner than expected.” “The 2020 fires completely changed the landscape of the park and the ongoing storms in recent months have caused some additional damage to public roads and trails. Despite this, repair works continue as planned and we’re making significant strides.” But it’s the longer term changes which worry Mr McNamara. He has noticed, for example, the appearance of European wasps on higher ground. They do not pollinate plants so their appearance transforms the ecology. “We need to be aware of the impact we are all having upon our environment. “You don’t wake up the following morning and see those impacts. They happen over time. “We Europeans have only been here for a couple of hundred years. We need to understand that what we do today has implications well into the future on a time scale that is very difficult for us to appreciate.”

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/steve.evans/9c890a8b-1202-4eaa-ac7a-94fd54a46b9b.jpg/r3_297_5566_3440_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

The hurt to Namadgi one year after the great fire

/images/transform/v1/crop/frm/steve.evans/9c890a8b-1202-4eaa-ac7a-94fd54a46b9b.jpg/r3_297_5566_3440_w1200_h678_fmax.jpg

How has Namadgi National Park recovered from the Orroral Valley fire?

news, latest-news,

2021-01-27T04:30:00+11:00

https://players.brightcove.net/3879528182001/default_default/index.html?videoId=6223966063001

https://players.brightcove.net/3879528182001/default_default/index.html?videoId=6223966063001

Brett McNamara on fire and Namadgi

One year after the vicious fire which devastated 80 per cent of the Namadgi National Park, greenery is creeping back to the Orroral Valley.

But it is a deceptive greenery, according to Brett McNamara, the manager of the park on Canberra’s doorstep that seems like the lungs of the city.

Look a little harder and you see signs of long-term damage. You can find them if you know where to look – and Mr McNamara knows where to look.

He talks of his feeling of sadness.

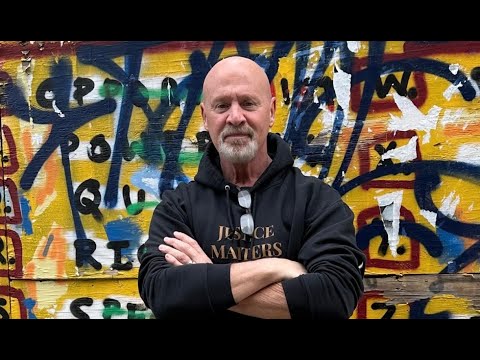

Brett McNamara overlooks the Orroral Valley one year later. Picture: Karleen Minney

Creeks which should be flowing with water remain dry, silted with what he calls “slugs” of piled-up sludge.

“To have come here before that fire, we would have found a babbling little creek, perhaps two metres deep. water flowing through this landscape,” Mr McNamara says.

“But post-fire, with the amount of debris and the movement of sediment across this landscape, this has now formed a sediment slug,” he said.

“This actually deprives native fish species of their habitat. We often think about the loss of mammals and insects but we don’t necessarily thinks about the impact on the aquatic environment.”

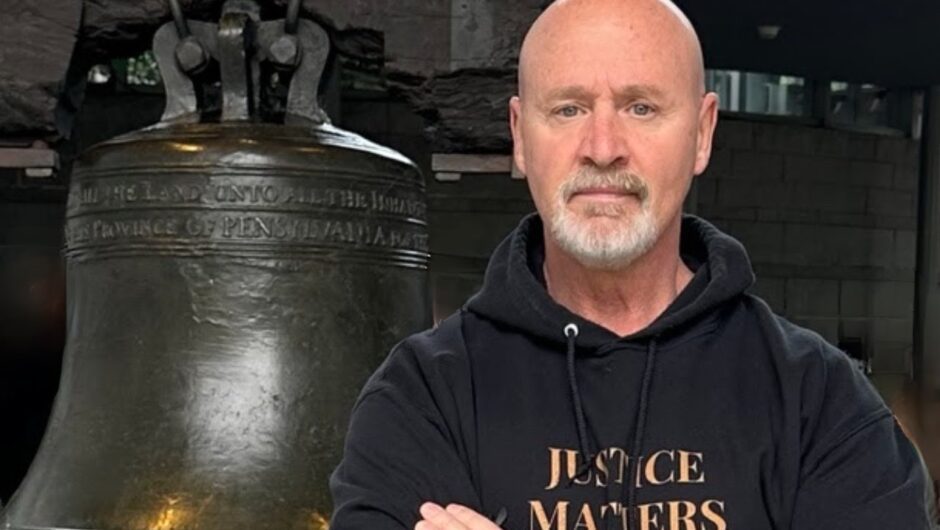

The ignition point of the Orroral Valley fire on January 27, 2020. Picture: Department of Defence

And, most importantly, the source of Canberra’s water remains damaged and fragile.

When the surveyor Charles Scrivener searched for a site for the nation’s as-yet unbuilt capital, he hit on this area because of the bogs which would soak up water and then release it.

Last year’s fire burnt so much vegetation and sent so much debris into the bogs that their life-giving abilities are impaired. Wild animals trample them.

“We have the pressure of feral deer coming onto these bogs. We also have the pressure of horses impacting on the bogs,” Mr McNamara said.

“The impact of invasive species and fire has the potential of actually altering the functioning ecosystem of these bogs.

“If the frequency of fire keeps impacting on the ecosystems, we actually start seeing the loss of water supply to the nation’s capital.”

The Orroral Valley fire burns on the night of January 27, 2020. Picture: Sitthixay Ditthavong

The fire was so devastating that the core of the park in the valley itself remains closed to the public. Tracks which were passable before the fire remain impassable today. Bridges which would have taken the weight of a truck are now too weak.

It’s not so much the impact of one fire which worries Mr McNamara but the repeated impact of ever more intense and frequent fires. This heightened fire activity caused by global warming means the forest doesn’t have the chance to recover. In his 30 years at the park, its appearance has changed dramatically.

The forest used to be thick but now trees don’t get time to grow before the next fire. “It’s a very different forest from what it was in the 1990s when I first started working here.

“To witness the mountains burn once back in 2003 was confronting, but to have seen the mountains burn twice in one career tells you that there’s an ecological change that is occurring within these mountains.”

One of the reasons last year’s fire was so bad was that it came after years of drought. Treading on tinder-dry grass was like stepping on corn flakes. The canopy, the tops of trees, was actually dead.

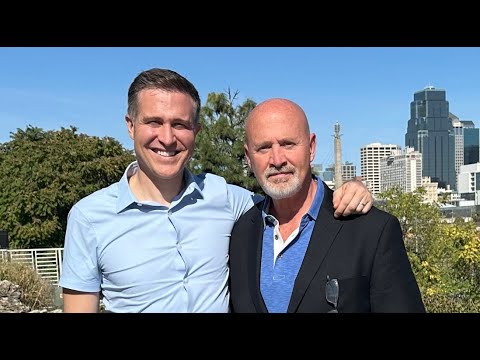

Brett McNamara mourns the loss of thick forest as fires get more frequent. Picture Karleen Minney

The recovery currently underway in the park is “tainted with a sense of what does the future hold for us if we are to experience fire again and again with such intensity. This is where the question is unanswered. What these mountains will look like well into the future?”

As he fears for the future, he remembers the past. The experience of a year ago is seared on his mind. He was in the park, fighting the fire, feeling its scorching danger. “There were moments when the fire was just coming down on top of us and we really did fear for our lives,” he says.

The work of recovery continues, though with still no date for the re-opening of the core of the national park.

The ACT’s Minister for Planning, Mick Gentleman said there was “excellent progress on our long-term bushfire recovery plan. We’re moving faster than we originally anticipated and I’m optimistic that more areas will be able to open sooner than expected.”

“The 2020 fires completely changed the landscape of the park and the ongoing storms in recent months have caused some additional damage to public roads and trails. Despite this, repair works continue as planned and we’re making significant strides.”

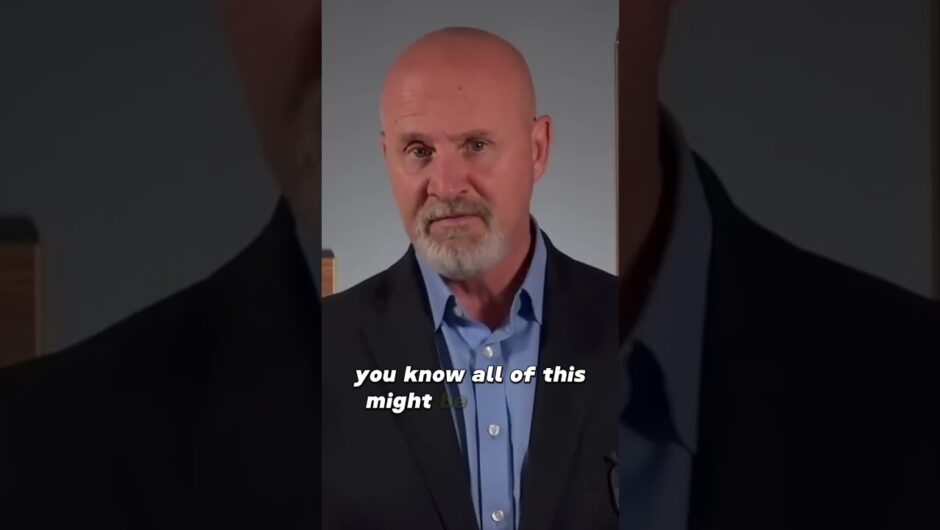

Dried creeks are still dry and full of silt one year on. Picture: Karleen Minney

But it’s the longer term changes which worry Mr McNamara. He has noticed, for example, the appearance of European wasps on higher ground. They do not pollinate plants so their appearance transforms the ecology.

“We need to be aware of the impact we are all having upon our environment.

“You don’t wake up the following morning and see those impacts. They happen over time.

“We Europeans have only been here for a couple of hundred years. We need to understand that what we do today has implications well into the future on a time scale that is very difficult for us to appreciate.”